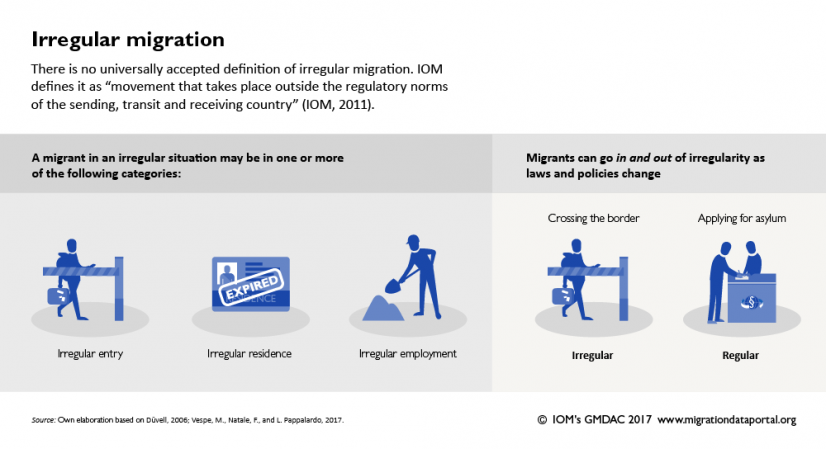

Irregular migration

Reliable statistics on stocks or flows of irregular migrants, the well-being of migrants in irregular situations, or the extent to which they have access to services such as health and education, are generally not available. Irregularity does not refer to the individuals but to their migratory status at a certain point in time. Changes in national laws and policies can turn regular migration into irregular migration, and vice-versa. The status of migrants can change during their journey and stay in the country of transit/destination, which makes it difficult to have a comprehensive picture of irregular migration and the profiles of irregular migrants. Terms such as “irregular”, “undocumented” and “unauthorized” are often used interchangeably.

Definition

There is no universally accepted definition of irregular migration. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines it as “movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving country” (IOM, 2011). A migrant in an irregular situation may fall within one or more of the following circumstances:

- He or she may enter the country irregularly, for instance with false documents or without crossing at an official border crossing point;

- He or she may reside in the country irregularly, for instance, in violation of the terms of an entry visa/residence permit; or

- He or she may be employed in the country irregularly, for instance he or she may have the right to reside but not to take up paid employment in the country.

It is important to note that the phenomenon of irregular migration refers to both the movement of people in an undocumented fashion, or irregular migration flows, and the number of migrants whose status may, at any point, be undocumented, or irregular migrant stocks. (Vespe, M., Natale, F. and L. Pappalardo, 2017). Changes in irregular migrant stocks in a country can occur not only due to undocumented migrants entering or leaving the country (irregular migration “inflows” and “outflows”, respectively), but also due to changes in status for migrants already in the country, from undocumented to documented or vice-versa.

Irregularity refers to the status of a person at a certain point in time or during a certain period, not to the person. Migrants can go “in and out” of irregularity as laws and policies change (see Düvell, 2006, Vespe, M., Natale, F. and L. Pappalardo, 2017). For example, migrants escaping conflict and persecution in their countries and seeking protection in another country may be counted as irregular migrants at the moment of crossing the border, but their status may become regular once they apply for asylum (see Vespe, M., Natale, F. and L. Pappalardo, 2017, IOM, 2017). Also, migrants with regular status in a country may become undocumented upon expiration of their visa or permit.

In some cases, the classification of movements as “irregular” is more nuanced. For example, the Free Movement Protocol of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) allows people to move freely among the 15 member states and stay for up to 90 days provided they are in possession of valid travel documents. As migrants in the region do not always carry the required documentation or do not cross at official border posts, such crossings in the region are mostly considered “undocumented” or “irregular” while the movement in itself is not if conducted with valid travel documents.

Recent trends

Irregular migration is difficult to track as it occurs outside the regulatory norms of countries and usually with the aim of avoiding detection. Changes in the migration status of an individual, into or out of irregularity, are also hard to track. As a result, current knowledge of irregular migration levels and dynamics is limited, particularly on a global scale.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of borders as containment measures has dramatically impacted the social, economic and political situation in many regions, leading to a decrease of regular mobility pathways, streams of income and remittances (Sanchez & Achilli, 2020; ICMPD, 2021; UNODC, 2021).

While official figures show that irregular crossings have partly decreased due to tighter border controls and restrictive COVID-19 migration policies - In 2020 the European Border and Coast Guard Agency FRONTEX reported the lowest level of irregular migration to the EU since 2013 due to COVID-19 (FRONTEX, 2021) - research suggests that no increase of regular migration pathways and a potential unequal recovery from the downturn of many economies, may actually increase the demand for smuggling services in the medium to long term and lead to an increase in irregular labour migration (UNODC, 2021; UNODC, n.d.). One possible example of this is at the United States – Mexico border, where data on US Border Patrol apprehensions of migrants after crossing the border irregularly is available. 2020 saw a decrease from more than 900,000 apprehensions in 2019 to just under 500,000 in 2020, but in 2021 more than 1.5 million apprehensions were reported at the United States’ southern border (US CBP, 2022).

Countries and regions for which some recent stock estimates are available include:

Asia

Estimates suggest that there were some million undocumented migrants in Pakistan in 2013 (Gallagher and McAuliffe, 2016), and about 1.23 to 1.46 million irregular foreign workers in Malaysia in 2017 (Yi et al, 2020).

Other Asian countries host significant irregular migrant populations, although the lack of reliable data and estimates make it very difficult to assess the actual extent of irregular migration and migrant smuggling trends in these regions (McAuliffe and Laczko, 2016).) In 2013, it was estimated that approximately 2.7 million irregular migrants from Afghanistan lived in Pakistan and 2.25 million undocumented Afghan migrants lived in Iran (UNHCR, 2021).

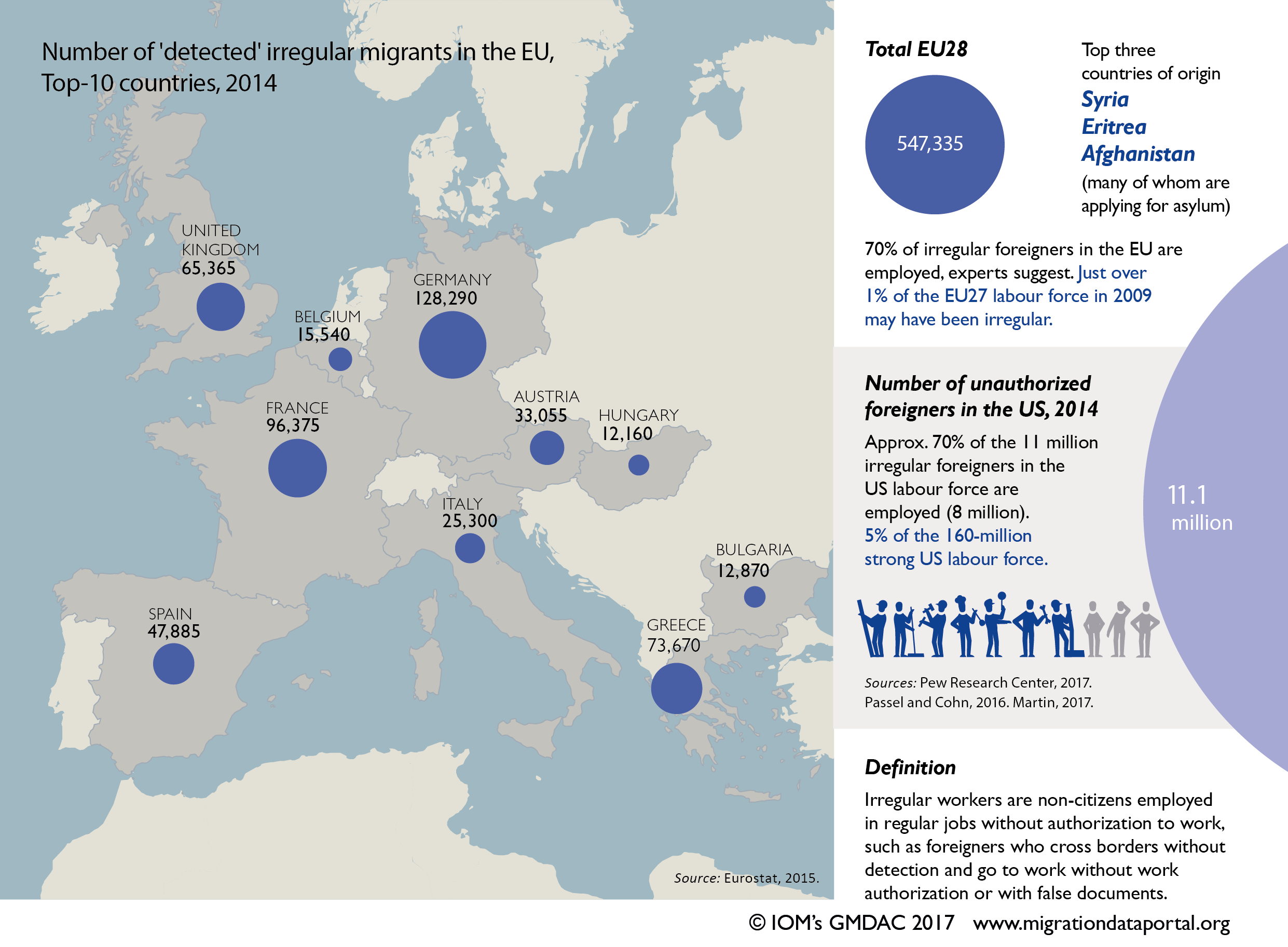

Europe

The size of the irregular migrant stock of the EU-27 in 2008 was measured to be between 1.9 and 3.8 million, a decline from between 2.4 and 5.4 million in the EU-25 in 2005 (Kovacheva and Vogel, 2009).

United Kingdom

The most recent estimates of the stock of irregular migrants in the United Kingdom point to 674,000 individuals residing in the country, but these numbers may vary in size depending on the methodology used and on the groups included to tally the number of irregular migrants, as some include asylum seekers and UK-born children of irregular migrants (MO, 2020).

United States

An estimated 11.4 million undocumented migrants were living in the United States (US) as of 2018 (Baker, 2021)

Countries and regions for which some recent flow estimates are available include:

Africa

While there are significant irregular migration movements occurring within Africa, in particular in West Africa (see nuances in definition above), to Northern Africa, to the Horn of Africa (often en route to the Arabian Peninsula) and towards South Africa, data on irregular migration flows in the African context is scarce with only a few sources available on certain routes (IOM, 2020).

In the East and Horn of Africa (EHoA) region, migration flows on the “Eastern route” across the Golf of Aden to Yemen on to Saudi Arabia and, to a lesser degree, along the “Southern route” from the Horn of Africa to South Africa have been well documented. In 2021, IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) recorded over 269,000 movements along the Eastern route, accounting for 40 per cent of all movements (674,243) in EHoA (IOM, 2022). In the first quarter of 2022, IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) recorded the arrival of almost 20,000 East African Migrants in Yemen (IOM, 2022), an 69% increase compared to the final quarter of 2021 (MMC, 2022). On the Southern route, DTM recorded 58,648 movements along this route in 2021, comprising about 9 per cent of total movements in EHoA for that year (IOM, 2022).

Asia

Within Asia, Afghanistan is one of the main countries of origin of migrants and refugees. However, Afghan nationals often must cross borders irregularly after being forcibly displaced, with many of them moving to Pakistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. These countries are estimated to host a large number of Afghans (UNDOC, 2015; Triandafyllidou and Maroukis, 2012).

South Eastern Asia is characterized by a large degree of irregular migration within the region, with Thailand and Malaysia appearing as major destination countries. An estimated one-third of migrant workers in the Asia-Pacific region have an irregular status in their country of destination (ILO, 2011).Existing estimates suggest that a large number of Cambodians move irregularly to Thailand – over 120,000 in 2009, and that 55,000 Cambodians are smuggled into Thailand yearly (UNDOC, 2015). UNODC estimates suggested that every year more than 660,000 migrants from Cambodia, Myanmar and Lao PDR migrate to Thailand in an unauthorized fashion (2015).

Europe

There was an increase in the number of irregular movements into the region in 2015, compared to previous years, with over 1 million people arriving to Europe by sea (IOM, 2015). In that year, the Eastern Mediterranean route (mainly from Turkey to Greece) became the predominant route for migrants and asylum-seekers, as opposed to the Central Mediterranean route (from North Africa to Italy). Irregular arrivals to Greece by land and sea surpassed 900,000 in 2015, eleven times higher than in 2014 (IOM, 2015). In 2016, the total figure dropped significantly though it was still at higher levels than previous years; 387,895 irregular migrants reached Europe by land and sea (IOM, 2017).

In 2020, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency FRONTEX reported the lowest level of irregular migration to the EU since 2013 due to COVID-19 (FRONTEX, 2021). In 2021, FRONTEX reported an increase of irregular border crossings by 60 per cent compared to 2020, with 199,900 people detected in total (FRONTEX, 2022), though the number of detections remains lower than many pre-pandemic years.

In terms of intra-regional irregular movements, in 2021 the United Kingdom’s Home Office reported that there were 28,526 people detected arriving irregularly on small boats from France to the UK, a very sharp increase from the 8,43 detected in 2019 and 1,843 in 2018. Most of these passengers were crossing the English Channel and were originally from Iran, Iraq, Eritrea or Syria. (Home Office, 2022).

United States

The number of Mexicans crossing the US border irregularly has increased dramatically in 2021 (Gramlich and Scheller, 2021). In 2021, the US border patrol encountered 1.52 million irregular migrants on the U.S.-Mexico border; in 2020, that number was 491,000 (USBP, 2022). The number of non-Mexicans apprehended is higher than that of Mexicans in 2021, a new trend in recent years caused primarily by an increase in the number of irregular border crossings by people from Ecuador, Brazil, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Haiti and Cuba, many of whom seek asylum in the United States: (Gramlich and Scheller, 2021).

Data sources

The most commonly available data on irregular migration are derived from national administrative sources measuring compliance with migration legislation, not irregular migration per se. Data on irregular migration on a number of stock and flow indicators available from the following sources:

Stock indicators:

- Applications for regularization or voluntary return programmes;

- Implementation of forced returns;

- Detection of irregular stay in the country; or

- Sanctions incurred by employers of undocumented migrants.

Flow indicators:

- Border apprehensions, or

- Refusals of entry into a country.

In addition, population censuses or household surveys may in some cases include questions on migrants’ legal status. Even when they do not, these sources can be used to estimate the stock of undocumented migrants in a country.

One example of how to measure irregular migration from traditional data sources comes from the Pew Research Center. More specifically, the Center uses the American Community Survey, the Census and the Current Population Survey to estimate the total foreign-born population in the US. The number of people residing legally in the US is derived from demographic estimates of lawful permanent residents (LPRs). The latter figure is subtracted from the total number of foreign-born individuals, yielding the estimated number of undocumented immigrants in the country.

Available data on irregular migration flows

Africa and the Middle East

The Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) manages the Mixed Migration Monitoring Mechanism Initiative (4Mi), which collects and analyzes data on irregular migration flows: 1) from Somalia and Ethiopia and through Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti to Yemen and Saudi Arabia; 2) from the Horn of Africa towards Libya and crossing the Mediterranean into Europe; and 3) through Kenya and Tanzania to the Republic of South Africa and beyond. Data are collected through a network of 30 locally-recruited monitors in strategic migration hubs and published in Monthly Summaries and Trend Analysis reports.

The Mixed Migration Hub (MHub), working on behalf of the North Africa Mixed Migration Task Force, provides knowledge and research on mixed migratory movements in North Africa and the human rights protection issues faced by people on the move, based on routes, flows and trends within the region. MHub produces monthly trend bulletins to provide context to the changing migratory routes within North Africa, as well as in depth research publications. MHub also conducts field surveys with migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers along key migratory routes within the region in order to increase data collection and outline country and regional level mixed migration trends.

IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) collects data on different types of population movements, including on irregular migration through their Flow Monitoring System (FMS). IOM’s DTM has been active in over 60 countries since 2004. Data are regularly published in situation reports. Most of DTM’s FMS operations take place in Africa, including Mali, Nigeria, Libya, Chad, Cameroon, and Sudan, to name a few. Another FMS operation monitors arrivals to Italy, Greece and Spain.

The Americas

The Organization of American States (OAS) collects and publishes data on irregular migration flows to and within the Americas. The latest report was published in collaboration with IOM and presents data on irregular migration flows to/within Central American countries (Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Panama, Mexico) and Colombia from Africa, Asia, Cuba and Haiti from 2012 to August 2016.

The OAS and OECD’s Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI) also provides some statistics on irregular migration, which are published in the International Migration in the Americas reports.

Europe

Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical office, regularly reports on migration and migrant population statistics and on asylum statistics, and collects the following data on:

Enforcement of immigration legislation:

- Refused entry at the external borders

- Third-country nationals found to be irregularly present

- Third-country nationals ordered to leave

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, publishes data on “irregular border crossings”, “detections of irregular stay” and forced and assisted voluntary returns in its quarterly and annual Risk Analysis reports.

From 2000 to 2013, the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) published the “Annual Yearbook on Illegal Migration, Human Smuggling and Trafficking in Central and Eastern Europe”, which included a survey analysis of border management and border apprehension data from 22 countries.

IOM collates data on irregular migration flows from national authorities, coast guards, police forces and other relevant authorities. These data are published on the IOM Migration Flows – Europe website.

Irregular migration is intertwined with the smuggling of migrants, which is defined as the act of enabling the irregular entry of another person for financial or material gain (UNODC, 2017). Hence, data on irregular migration flows and data on migrant smuggling may often overlap, depending on a series of factors. For instance, certain irregular migration routes (such as those requiring a sea crossing) may be more difficult to travel without the assistance of smugglers. For more information about the relationship between irregular migration and smuggling see Carrera and Guild, 2016; Triandafyllidou and Maroukis, 2012; and The International Council on Human Rights Policy, 2010.

Available data on irregular migrant stocks

Asia-Pacific

The Asia-Pacific Regional Thematic Working Group on International Migration produced the Asia-Pacific Migration Report 2015: Migrants' Contributions to Development. The publication reiterates that data on irregular migration in this region are limited, but that a significant proportion of migration that occurs within and from the region is irregular, providing examples where country-level data are available.

The Americas

The Pew Research Center uses census, survey and administrative data to produce estimates of irregular migrant stocks (“unauthorized immigrants”) in the US (see the Data sources section above). Figures are updated yearly and are available for the period 2000– 2016.

The US Department of Homeland Security also published reports containing estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States from 1990 to 2012.

Europe

The CLANDESTINO Database on Irregular Migration provides estimates for 12 European countries, for the years 2007–2009, of irregular migrant stocks and their composition by age, sex, nationality and economic sector of activity. The database was created in the framework of the EU-funded research project CLANDESTINO. Since the termination of the project, information is updated occasionally.

Back to topData strengths & limitations

Given the clandestine nature of irregular migration and the fact that migrants’ legal status can be subject to frequent change, quantifying and recording irregular migrant stocks is difficult. The same goes for irregular migration flows, as these include inflows and outflows of irregular migrants, as well as migrants who move in and out of irregularity within the same country, and births and deaths within the irregular migrant population, which are all difficult to track (Ardittis and Laczko, 2017).

It is important to recognize that an ostensible increase in irregular migration figures may not necessarily reflect an actual increase in the number of irregular migrants, but rather changes in policies and practices related to border and migration controls, as well as other administrative criteria and programmes. For example, if criteria for family reunification change, some relatives may no longer be able to remain with their family members on their residence permits once these expire, thus becoming irregular. These issues hamper comparability of data collected within the same country over time.

For similar reasons, comparability of irregular migration data across countries may not reflect actual differences in levels of irregular migration, but rather differences in border control and administrative systems. It is also important to point out that cross-country comparisons of irregular migration statistics could be misleading because countries use different methodologies to collect data on the stock of irregular migrants, or may use different definitions of irregular migration, based on differing entry and stay regulations. Further, national censuses might understate the number of irregular migrants in a given country, as undocumented migrants may avoid census interviews (IOM, 2017).

Moreover, while information on irregular migration flows to Europe and the US is more readily available, less is known about the dynamics of irregular migration within Africa, Asia and Latin America, though irregular migration in these regions is estimated to be significant (Kraler, A. and D. Reichel, 2011). There are also wide differentials in availability of information about irregular migrants’ profiles.

Most importantly, data on irregular migrants’ wellbeing and access to basic services such as health and education are still very scarce and incomplete. These data are fundamental to address irregular migrants’ vulnerabilities, to monitor progress towards the achievement of migration-related targets in the Sustainable Development Goals, and ensure nobody is left behind due to his or her migrant status, be this regular or irregular.