Migration and health

Migration places individuals in situations which may impact their physical and mental well-being. Conditions surrounding the migration process may increase the vulnerability of migrants towards poorer health outcomes, or conversely enable wellbeing and access to healthcare. The impacts on the health of migrants have multiple determinants and may change over time. These impacts may differ across migrant categories and legal status. Migration also cuts across economic and social policies, human rights and equity issues, development agendas, and social norms – all of which are relevant to migration health. The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, the Global Compact of Migrants and Refugees and other international instruments have outlined data at the nexus of migration and health critically important to monitor the Agenda’s progress, including specific progress on the health-related goal and targets to ensure that “no one is left behind” irrespective of their migration status.

Definitions

Health is defined as a “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 2005).

Health is also a basic human right and an essential component of sustainable development; being and staying healthy is a fundamental precondition for migrants to work, to be productive and to contribute to the social and economic development of their communities of origin and destination.

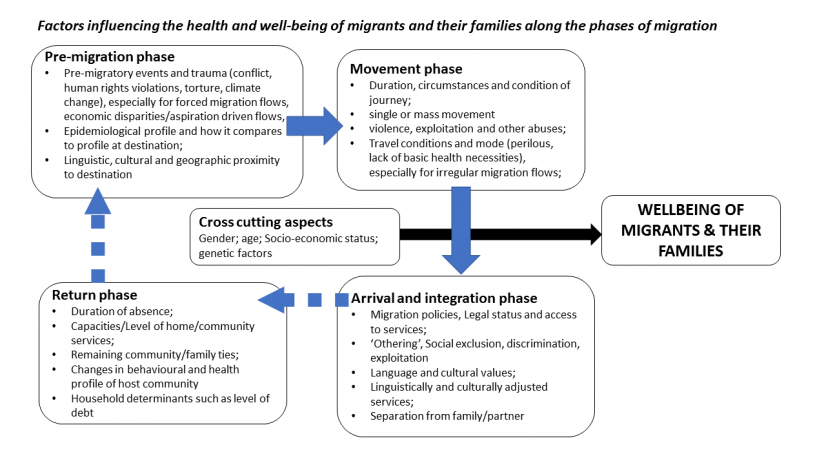

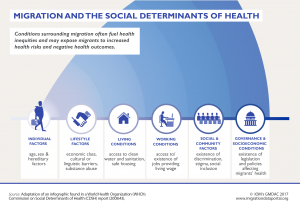

The concept of migration and health (or migration health) encompasses the idea that there are various factors and conditions that influence the health of migrants. These are referred to as social determinants of health (SDH). A range of socioeconomic, legal, cultural, environmental, and physical environments to individual factors such as lifestyle, age, hereditary, and behavioral factors that impact the health of migrants (Figure 2). Migration itself is considered a social determinant of health because of its potential to impact health outcomes due to factors such as changes in living conditions and access to healthcare. Migrants’ health care access is also to a large extent determined by the availability, accessibility, acceptability, appropriateness, affordability and quality of services in the host community or country. There may be differences in the disease profiles and health risk factors between migrant and host populations, or inequalities in the access/uptake of preventive interventions and in treatment outcomes.

The relationship between migration and health is complex. and its impact varies considerably across migrant groups, from person to person within such groups, and during the phases of migration (Figure 2). Migrants are affected by social inequalities and are exposed to several experiences during the migration process which put their physical, mental and social well-being at risk. Conditions surrounding the migration process may exacerbate health vulnerabilities and risk behaviors. Conversely, it can be an enabler for achieving better health trajectories, such as the case of a newly arrived refugee as part of a humanitarian settlement programme getting access to treatment for a chronic disease. Due to their irregular status, stigma, discrimination, language, cultural barriers and low-income levels, irregular migrants may be excluded from accessing primary health care services, vaccination and health-promotion interventions.

A growing body of research evidence points to varying gradients of benefits and risk factors for the health of migrants (and their families) through the stages of migration (BMJ, 2024; WHO, 2022; PLOS, 2020) (Figure 2). The process of migration includes different phases (pre-departure, travel and transit, destination and integration, and return), where the health of migrants can be adversely affected or be positively enabled. The interplay and impacts of migration on the health of migrants themselves. Human mobility may also impact on public health with respect to the prevention and control of emerging infectious diseases. For instance, moving from a country with high malaria endemicity to one which is on verge of elimination.

Some countries/territories enforce mandatory detention for many irregular migrants where health-related vulnerabilities may exacerbate due to lack of access to health services, nutrition, inadequate hygiene and sanitation within densely populated living spaces, and violence. The length of detention has been associated with the severity of mental disorders and psychosocial issues.

Many international migrant workers are employed in precarious work settings, within dangerous, difficult and demeaning (3Ds) jobs (ILO, n.d.), with low wages, hazardous working conditions, with limited social protection and occupational health rights. Migrants’ access to health services has increasingly been a key indicator of people-centered, rights-based, inclusive and equitable health systems that aim at reducing health inequities, but the social exclusion of vulnerable migrant groups continues to be common in the absence of explicit affirmative policies.

Back to topData sources

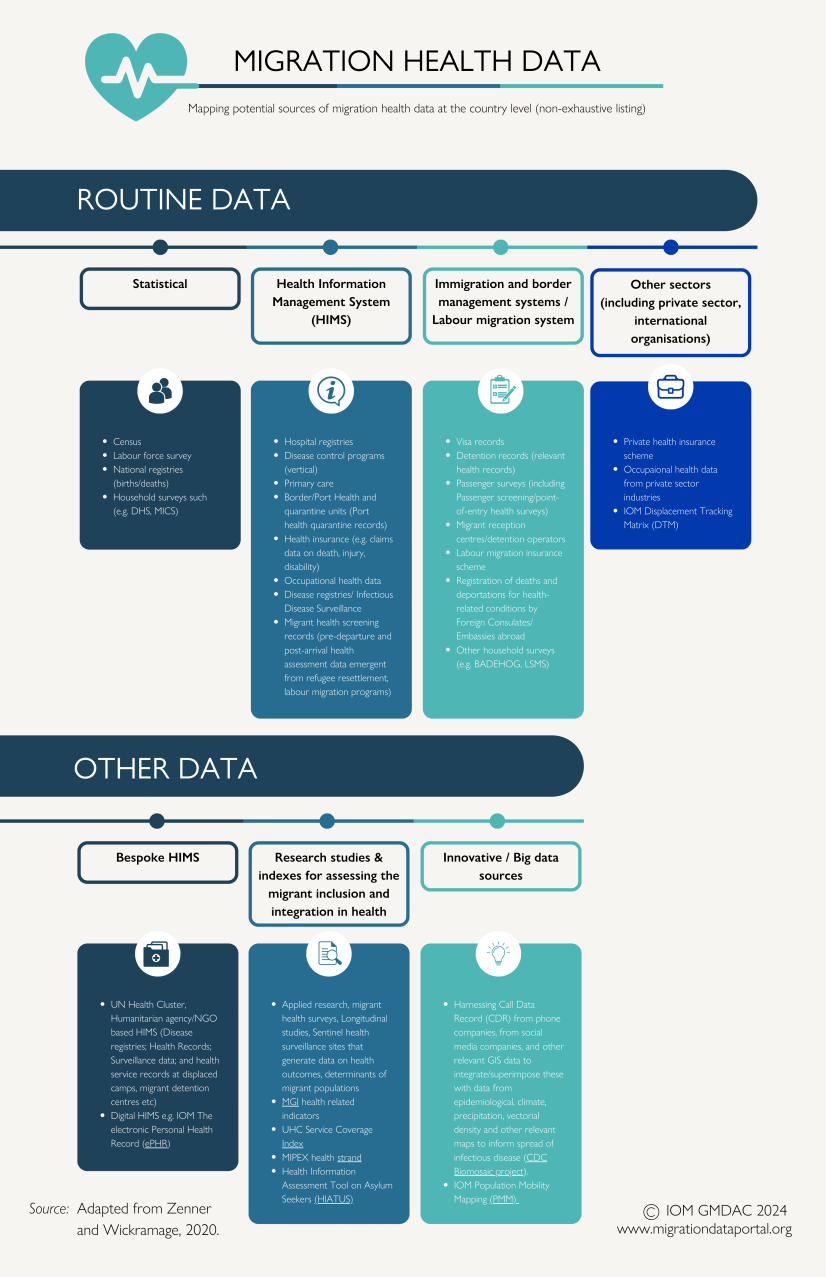

Migration health data may be broadly defined as data relevant to characterizing the health and social determinants of various migrant populations (e.g. the non-communicable disease burden in international labor migrants); data relating to extent of access to health care system by migrant typology; to data to better understand disease spread across geospatial areas along human mobility pathways. Data can be both quantitative, such as epidemiological profiles on refugee populations; and qualitative, describing risk and resiliency factors.

Despite the clarion calls for better migration data to inform public health policy and practice, migrants are largely invisible in official data due to lack of integration of migration variables within routine National/Sub-National Health Information Systems (HIMS) (Vidal, E. M., & Wickramage, K. P., 2024). Routine data sources range from population health surveys, (vertical) disease control programs, hospital registries to health insurance schemes (Table 1). The lack of inclusion of migrant variables within HIMS makes disaggregation of health outcomes by migrant status challenging – making it hard to track progress at national/global levels, leading to opinion based, rather than evidence-based decision making.

Migration health data exists not only within health sector but may also be collected through operations/services rendered by other sectors such as Immigration and border management, refugee resettlement services, Foreign Employment Bureau, Health Insurance providers and through harnessing big data (Figure 3). Such sources of MH data often remain unmapped and unlinked to health authorities and HIMS. For instance, analysis of health insurance claims/payments made within international labour migrant health insurance schemes are housed within Foreign Employment authorities and can provide critical data on morbidities, injuries and deaths of outbound migrant workers, who often work precarious employment settings (IOM, 2021). There is a need to make better use of existing data captured through the health and migration management ecosystems. Methods such as data linkage may be used to ‘link’ disparate data sets and provide insights on migrant health outcomes, especially across the migration trajectory (Burns et al., 2019; Bozorgmehr et al., 2023).

The utilization of innovative ‘big data’ signifies a significant opportunity to harness migration health data in conjunction with sophisticated analytical techniques like machine learning. By harnessing diverse data sources such as mobile phone Call Data Records (CDR), satellites, and social media, and integrating/superimposing data from population mobility mapping methods (IOM DTM, HBMM) including community-based approaches (IOM PMM), data relevant to human mobility and health can be generated. In particular, the integration of CDRs acquired from telecommunications and social media platforms with relevant Geographic Information System (GIS) data, alongside a broad array of datasets encompassing epidemiological maps, climatological maps, precipitation maps, and vectorial density data, flight and travel information, has emerged as a potent approach for comprehending the dynamics of infectious disease transmission (Li et al., 2023, Perrotta et al., 2022). This multifaceted strategy enables a better understanding of disease spread patterns and facilitates the development of targeted interventions.

Examples of Routine data sources at the national/sub-national level:

A) Civil registration, vital statistics and population censuses:

Administrative data sources and censuses provide information on the births and deaths (and cause of deaths) of people. If information on a person’s length of stay/date of entry into a country, citizenship status and country of birth are captured, such data may identify whether someone is a migrant, and be used to analyze health outcomes based on these variables. However only very few countries capture variables by migratory status (Bozorgmehr et al., 2023).

In Denmark, a comprehensive Civil Registration System (CRS) assigns a unique 10-digit Civil Personal Register number to all individuals, including refugees and specific migrant groups. This system records vital data such as country of birth, citizenship, date of immigration, and parental nationality, aiding in the identification of refugees and migrants. Additionally, the personal identifier is interconnected across various national registers, including health, education, and labor. By integrating these systems, health information can be efficiently linked with migration indicators, reducing the burden on healthcare personnel by eliminating the need for independent data collection. The CPR-number can also be utilized within data-linkage as an important research tool in epidemiological research e.g., as regards cancer and psychiatric epidemiology. It is possible to investigate the association between disease or death in individuals and place of birth and residence, immigration and emigration status and environmental exposures at place of residence.

B) Household surveys:

Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are nationally representative household surveys that provide data on a wide range of health- and nutrition-related information. The program has collected data through more than 400 surveys in over 90 countries. The high-income countries that are often the destination for international migrants normally do not conduct household surveys. Respondents to DHS are usually female head of households, and such surveys are tailored to the needs of a particular country while containing several basic components that are comparable across all countries. DHS surveys are not designed to specifically target international migrants in the sampling design. In the DHS-VII, international migrants are those who choose "abroad" in response to the variable "region of previous residence". To identify non-migrants the DHS uses "years lived in place of residence". While there are clear limitations to this migrant variables/identifier, DHS data can beused toanalyze health outcomes collected in survey. A 2012 review of 85 DHS national surveys found that a dedicated module with detailed information on migration was only be present in 12 surveys. For children, their migration status can sometimes be identified through their mothers' migration status. In cases where a separate section on international migration appears in the questionnaire, children who left the household to go abroad can also be identified, along with their basic characteristics.

Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) is a household survey programme developed by UNICEF in the mid 90's to assist countries in filling data gaps for monitoring the situation of children and women. It is capable of producing statistically sound, internationally comparable estimates of these indicators. In the 6th iteration of the survey (MICS6), two types of migratory status are featured: international migrant and non-migrant (which includes internal migrants). For MICS, international migrants refer to those who choose "overseas/outside of country" in response to the variable "place of living prior to moving to current place" and "province prior to moving to current place". The survey also uses different variables from DHS to identify non-migrants. The MICS uses "duration of living in current place". In the MICS, respondents who answer "always/since birth" are included as non-migrants.

Findings from household surveys:

The immunization of children is paramount for maintaining public health and community well-being. Measles, one of the most highly contagious viruses to humans, serves as a barometer for both inadequate vaccination coverage and limited access to essential healthcare services, particularly among vulnerable populations. Analysis of survey data available only from 8 out of 15 countries published by WHO reveals lower measles vaccination rates among international migrant children compared to those in the host population, highlighting disparities in healthcare accessibility and the need for targeted interventions (Table 1).

Table 1: Children who received Measles vaccination, by migrant status (percentage)

|

Country |

Survey/ Round* |

Year |

International Migrant |

Host population |

|

Armenia |

DHS-VII |

2015-2016 |

27.3% |

60.5% |

|

Benin |

DHS-VII |

2017-2018 |

45.0% |

47.5% |

|

Burundi |

DHS-VII |

2016-2017 |

63.0% |

69.3% |

|

Cameroon |

DHS-VII |

2018 |

32.7% |

49.9% |

|

Central African Republic |

MICS6 |

2018-2019 |

55.6% |

54.2% |

|

Ethiopia |

DHS-VII |

2016 |

39.7% |

41.3% |

|

Gambia |

MICS6 |

2018 |

86.7% |

85.0% |

|

Guinea |

DHS-VII |

2018 |

37.1% |

30.5% |

|

Guinea Bissau |

MICS6 |

2018-2019 |

79.2% |

82.8% |

|

Guyana |

MICS6 |

2019-2020 |

0.0% |

69.0% |

|

Indonesia |

DHS-VII |

2017 |

68.9% |

59.3% |

|

Jordan |

DHS-VII |

2017-2018 |

54.5% |

55.3% |

|

Lesotho |

MICS6 |

2018 |

0.0% |

70.6% |

|

Liberia |

DHS-VII |

2019-2020 |

56.3% |

51.1% |

|

Malawi |

DHS-VII |

2015-2016 |

65.9% |

68.8% |

|

Mali |

DHS-VII |

2018 |

57.4% |

49.4% |

|

Nepal |

MICS |

2019 |

92.9% |

85.6% |

|

Sao Tome and Principe |

MICS6 |

2019 |

|

71.7% |

|

Sierra Leone |

DHS-VII |

2019 |

54.8% |

56.6% |

|

Suriname |

MICS6 |

2018 |

42.9% |

60.6% |

|

Thailand |

MICS6 |

2019 |

90.9% |

91.9% |

|

Togo |

MICS6 |

2017 |

62.7% |

65.5% |

|

Tonga |

MICS6 |

2019 |

66.7% |

81.6% |

|

Zimbabwe |

MICS6 |

2019 |

90.0% |

80.9% |

*Dataset reproduced from: World report on the health of refugees and migrants. For DHS, refers to children born in the last 3 years who received measles vaccine 1. They are considered to have received the vaccine if it was written on the child's vaccination card or reported by the mother. For MICS, refers to children ever given MR vaccination.

Household Survey Databank (Banco de Datos de Encuestas de Hogares; BADEHOG): is a repository of The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). It is made up of a set of household surveys conducted by the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean since the 1990s. These surveys are conducted by the National Statistics Offices or other public agencies of the respective countries and share the characteristic of being the source of information officially used to measure poverty, inequality and various social indicators. BADEHOG indicators vary slightly between survey countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Response used to assess migratory status is emergent from question: "Where were you born?", with values that include terms such as bordering country, other country or outside of the country.

The Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) is another household survey programme focused on generating high-quality data for evidence-based policy making. The migration module of LSMS surveys typically includes questions on place of birth, most recent place of residence, reasons for moving, number of times moved and types of migration (including inter-district, rural-urban and international migration).

C) Disease control programs: Mobile and migrant populations pose a unique challenge to disease elimination campaigns as they are often hard to survey and reach with treatment. There is increasing recognition by national disease prevention and control programs, such as tuberculosis and malaria, in adopting migrant inclusive strategies at national, sub-national and cross-border level to meaningfully control disease spread, limit (re)introduction (Adams et al., 2022; WHO, 2015). Regional cooperation efforts to combat disease spread via migration routes have led to establishment of ‘cross-border’ data collection and joint-monitoring mechanisms such as the Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance programme.

D) Health institution-based records: National Hospital Registries provide data on health-related information pertinent to hospitalization, and National Epidemiological Disease surveillance systems provide information on diseases, conditions and outbreaks that may affect public health. However, most providers and insurers do not routinely collect data by legal status or on the national origin of the cases registered. Name-based algorithms have been used as an etiological tool to “data-mine” such registries to provide valuable information on health status. Such approaches in cancer registries have been utilized in effectively comparing disease burden among migrant groups (Razum et al., 2001).

E) Migration Health Assessment Records: Some states mandate migrant screening for selected disease conditions at pre-departure as pre-condition to travel for purposes of work, study, humanitarian/refugee resettlement, for family reunification etc. Post-arrival screening of migrants of migrants also take place on mandatory requirement or on voluntary basis. Data from such health assessments provide important data sources of various migrant populations but remain poorly analyzed and often unliked to National Health Systems (Wickramage & Zenner, 2019; Wickramage & Mosca, 2014).

In 2022, IOM provided reporting of 904,000 health assessments of immigrants and refugees. IOM also generates applied research and analytics of the health profiles of refugees to inform policy and practice (Deal et al., 2019; Pernitez-Agan et al., 2019). The information can be used to better understand the prevalence of diseases such as tuberculosis, conditions such as malnutrition and new pathologies among populations examined, to enable health authorities in both sending and receiving countries to better address the health of migrants.

F) Health Insurance Claims Data from Foreign Employment Bureaus, Migrant Worker Insurance agencies and Occupational Health Surveys: Health insurance claims of migrant workers and their families from providers (both government and private sectors) may provide data on morbidities, mortality (in case of migrant worker deaths), disability and data on deportations based on medical grounds. Systematic review and meta-analysis on migration and occupational health of international migrant workers employed in 13 countries and territories from 25 low-income and middle-income countries, mostly employed in unskilled manual labour found that migrant workers are at significant risk of work-related ill health and injury (Hargreaves et al., 2019). Migrant workers had various physical and psychiatric morbidities, and workplace accidents and injuries were relatively common.

G) An IOM report in 2021 provided an assessment of available sources of data on migrant worker fatalities at the global, regional and country levels. Key sources include national employer notification and social insurance systems, migrant welfare funds, embassies in destination countries and records of repatriated remains. The existence and quality of data are highly variable across countries, with knowledge concerning migrants mostly coming from middle- and high-income regions. Data on deaths of migrant workers in much of the developing world remain extremely scarce. The presence of relatively large informal sectors and loose health and safety regulation likely entail higher risks for native and migrant workers in regions of the world precisely where data are most lacking. However, poor quality and gaps in coverage limit the current usefulness of these data both for deepening understanding of trends and guiding intervention efforts. Measuring occupational fatalities is particularly challenging among undocumented and informal migrant populations, the groups most likely to have poor health and safety outcomes. Finally, although national population/labour statistics estimate that work-related diseases kill six times more people than fatal injuries, virtually no data are regularly and systematically produced at the national or international levels documenting occupational diseases among migrants.

Other Data Sources:

H) Bespoke HIMS: As outlined in recent reviews (Chiesa et al., 2019), Health information management in the context of forced migration and displacement are characterised by numerous stand-alone customized HIMS housed within humanitarian agencies and coordination clusters. These range from surveillance data and health service records at displaced camps, to bespoke data capturing systems. Health records, implemented specifically for forced migrant, seem to have the potential to address some of the challenges that they face in accessing health care, in particular in strategic hotspots, cross-border settings and for migrants on the move.

I) The IOM electronic personal health record (ePHR) provides an example of a bespoke HIMS platform to enhance health care workers’ understanding of migrants’ individual health needs. Prompted by increased arrivals to Europe in 2015 and 2016, a structured health record was developed to support health assessments for newly arriving migrants, with co-funding from the European Commission. This initiative evolved into a full electronic personal health record system within IOM, facilitating the secure transfer of information between health providers across different facilities and countries, critical given migrants' mobility. Currently operational in reception facilities across seven countries, including Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Serbia, and Slovenia, plans are underway to expand the system further. Additionally, with support from the Italian Government, the electronic Personal Health Record has been tailored to local needs in Sicily, featuring user-friendly interfaces, smart technology, and automated coding to minimize manual data entry. It offers real-time visualization of health status and disease demographics, meeting European exchange format standards, and informing health service provision and monitoring of illnesses and diseases according to International Health Regulations. Since its inception in January 2017, the system has captured 19,733 records of 14,440 individuals, predominantly young males. Nearly three-quarters of individuals did not have any recorded ICD-10 illnesses, with respiratory diseases and common infections being the most frequently reported health issues. Additionally, around 11% of individuals were recorded as having a mental illness in this cohort, reflecting a primarily young and healthy population exposed to adverse conditions and overcrowding in reception facilities, with a significant minority experiencing recent psychological trauma (Zenner et al., 2022).

J) Indexes/indicator frameworks assessing the migrant inclusion and integration in health:

The Migration Governance Indicators (MGI): developed by IOM to support requesting governments to examine the comprehensiveness of their migration policies and identify best practices and areas for potential improvement. While the MGI does not rank migration governance practices of countries, it provides a framework for governments at the national and local levels to gradually improve their migration management systems. Data collected in 100 countries between 2018 and 2023 show that in half of the assessed countries, all migrants have access to all government-funded health services under the same conditions as nationals, regardless of their migratory status (IOM, 2024).

The MIPEX Health strand: The MIPEX Health strand is a component of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), which evaluates policies aimed at integrating migrants in various countries. Specifically focusing on healthcare access, it assesses whether migrants have equal access to healthcare services as native-born citizens, the availability of health insurance coverage, cultural and language support for migrants within healthcare settings, access to preventive healthcare services, and the provision of mental health support. By examining these factors, the MIPEX Health strand provides insights into how effectively countries are addressing the healthcare needs of migrant populations and identifies areas for policy improvement.

K. Big data:

Big data presents opportunities to comprehend the influence of migration on the spread of infectious diseases, aiding in predicting outbreaks and addressing immediate health concerns of displaced individuals (Franklinos et al., 2021)

Additionally, big data applications can cater to the healthcare needs of settled migrants and pinpoint variations in patient responses to treatments, allowing for tailored healthcare interventions. A key consideration regarding the application of big data in migration health data and research is the ethical considerations and safeguarding practices are required when involving varied stakeholders in big data analytics.

BioMosaic is a software application that allows combining and visualizing immigration statistics, and health and demographic data. It was developed by the United States ’ Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Global Migration Health in collaboration with Harvard University and the University of Toronto. BioMosaic shows foreign-born populations, census demographic data, and health-data indicators to the US county level. Targeted health communications, or public-health interventions, can be developed with the application by identifying foreign-born populations clustered in specific areas, or link census data on social determinants of health, such as income, education, language proficiency and access to healthcare.

Back to topWay forward in Improving migration health data

Enhancing national capacity to collect, analyze, share and manage migration data is a cornerstone of effective migration data management. However, despite the clarion calls for better migration data, migrants are largely invisible within routine health information systems and health data. Investments in better migration health data is needed to help reduce the health risks and costs associated with migration, identifying resource priorities, calibrate financing and enhancing public health.Tracking health outcomes relevant to SDGs and disease control programs, and inter and intra country comparisons towards progress towards health goals become impossible without strategies to enable migrant inclusive health and migration management systems at national level. For instance, supporting countries to adopt a migration module on existing health surveys, disease-specific registries and improving sampling methods would provide greater depth of data. To make making the invisible visible, a number of strategies have been proposed (derived in part from the WHO World report on the health of refugees and migrants).

It is also important to consider that collecting and disseminating migrant health data raise significant ethical concerns, particularly regarding the right to privacy as outlined in Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, alongside security considerations. The protection and privacy of migrant health data are major concerns. The inappropriate sharing of data can have serious consequences, such as limiting access to health care and other services, or even deportation. Introducing new or harmonized systems could greatly enhance understanding of migration and migrant health, yet implementation must be closely supervised to guarantee anonymization of all data and secure sharing across various entities, given the substantial protection risks involved. Additionally, ensuring interoperability among national and regional databases containing migrant information is crucial for advancing efforts towards improved information systems.

|

Challenge |

Action |

|

The lack of reliable data on healthcare for migrants stems from several issues: data is not broken down by migratory status, collection methods are inconsistent, and the data does not accurately reflect diverse migrant populations (refugees, labour migrants, international students, asylum seekers etc). |

Develop a migration module – a consensus set of core variables to determine migratory status and develop capacities and approaches at country level to enshrine migration modules within existing health data collection systems. Recommendations for core variables:

To advance migration health data and research, it is essential to develop an inter-agency and inter-sectoral coordination mechanism, with participation of relevant government departments academia, civil society and migrant communities themselves. A first step would be mapping of existing migration health data collection within health sector, migration management ecosystem and other sources as outlined in Figure 3. Finding opportunities to include the migration module, adapt sampling designs and approaches in existing health surveys to ensure a good representation of refugees and migrants is also practical first step. Ensuring a clear and robust data protection and ethical framework on collecting migration health related data is an essential prerequisite before insertion of such migration modules to existing or newly developed collection systems. |

|

Limited capacity in developing countries, including least developed countries and small island developing States, in collecting high-quality, timely and reliable data. |

Strengthen the capacity in countries for collecting, analysing and reporting on health outcomes and burden of disease by key characteristics including sex, age and disability, as well as the ability for further disaggregation by subgroups of refugees and migrants, such as labour migrants, irregular migrants, asylum seekers and IDPs. Investigate approaches that address the interoperability of data sets – that is, the linking of different data sets to generate comprehensive data about a given group of individuals. This would help to ensure the interoperability of databases at national and global levels to permit the exchange of data and the generation of comprehensive data sets. |

|

National and international policymakers need to change the current narrative by moving from small-scale, unrepresentative and non-comparable data sets to robust, comparable and high-quality data, which would allow appropriate decisions to be taken at the local, national, regional and global levels. |

Explore various sources of information including civil registration vital statistics systems, administrative data from government HIS and, potentially, the untapped data sets collected by major commercial enterprises. Undertake a comprehensive review of all major data sets globally on health determinants, health status or health systems. Such studies are time and resource intensive but must be prioritized to develop a robust data and monitoring framework for health and migration. |

Importance of Migration Health Research

Migration Research becomes critical in a world where there is little data emergent from routine health and other systems. However, despite the steady increase in migration health research undertaken over the past two decades, the paucity of research evidence on international migration health is still significant, given the magnitude and complexity of migrant flows. For instance, migrant workers, especially those from developing regions comprise over half of all international migrants. Yet published research papers about labour migrants represent only 6·2% of the total international migration and health research output in the past 16 years (Sweileh et al., 2018). Less than 1% of research on international migration health published were from low-income countries.

Investments in research need to be linked to policy making. Enhancing capacities and mentorship among researchers in developing regions is crucial. The MHADRI network is the worlds largest network of migration health academics, researchers, UN and policy makers devoted to advancing migration health especially in the Global South. Research process at national/sub-national level linked to inter-sectoral policy making process with meaningful engagement of academia, migrants and civil society is powerful in galvanizing political action, leading to formulation of evidence based national migration health policies.

IOM Migration Health Research Portal: online portal is a repository of all migration health related data stemming from IOM’s global health programmes.The portal also houses the Migration Health Research Bulletin and the Migration Health Research Podcast (also streamed through Spotify) which are platforms to highlight key areas of research from IOM’s migration health programs globally.

To develop sustainable robust migrant sensitive health services, migration health data and research is critical for understanding the health conditions, social determinants, costs and the barriers to health care system accessibility, affordability, approachability, acceptability and appropriateness, and the migrants’ ability to perceive, to seek, to reach, to pay, to engage and advocate for health care.

Further reading

|

International Organisation for Migration |

|||||

|

2023

2023

2022

2022 |

International Organisation for Migration. Geneva. IOM Migration Health Research Portal International Organisation for Migration. Geneva. May 2022. International Organisation for Migration, Geneva. Migration Health 2021 Impact Overview August 2022. International Organisation for Migration, Geneva. |

||||

|

World Health Organisation |

|||||

|

2023

2023

2022

2022 |

Promoting the health of refugees and migrants: experiences from around the world March 2023. World Health Organisation, Geneva. Refugee and Migrant Health Toolkit January 2023. World Health Organisation, Geneva. World report on the health of refugees and migrants July 2022. World Health Organisation, Geneva. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. |

||||