This blog highlights a recent dataset comprising 49 countries with information collected between 2015 and 2019, with 17 more countries being assessed during 2020. The Migration Governance Indicators (MGI) cover countries of different levels of human development, and regions across the world, and are not limited to destination countries only, thus covering a wide range of issues related to migration beyond immigration regulations. The MGI is unique in using a definition of migration governance not just limited to rules and policies, but also including the institutional set-up in a country and procedures, for example on what actor leads on policymaking (IOM, 2019:136).

In analysing information on 49 countries collected between 2015 and 2019, three key findings stand out:

1. More comprehensive than expected

Looking at existing literature and datasets, one gets a certain bias towards developed immigration countries. However, in our sample, most countries govern both immigration and emigration aspects to some extent, ranging from protecting the rights of migrants, access to services, labour migration, diaspora and remittance policies. Migration governance in those countries is thus quite comprehensive, which should be better reflected in analytical approaches and frameworks on the topic more generally.

2. The silos remain

We have come a long way on migration being recognized as an important cross-cutting issue at the global level in the last years. Though considering that migration is an integral part of sustainable development, including urban planning and development financing, and that migrants are on the forefront when it comes to environmental impacts, migration policies are often not in sync with other policy domains at national level. There is a need to fully integrate human mobility considerations in other policy topics, such as human development, disaster management and climate change mitigation and adaptation, and not try to address them separately.

3. Identifying areas that can be strengthened

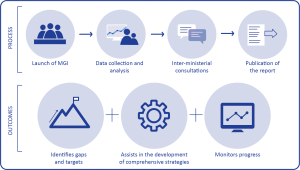

The MGI is an indicators-based process involving national consultations, which enables any country to assess its national migration governance framework. This in-depth approach based on country ownership helps national governments in identifying areas where migration capacities could be strengthened. For example, the approach can help countries to develop a coherent overall national migration strategy and/or one on reintegration of returning migrants, engaging the private sector in policymaking, tracing and collecting data on missing migrants or including migration-relevant aspects (age, sex, country of birth) in census questionnaires.

Way forward – what next?

Countries can already build on examples of migration governance existing around the world and learn from each other. Despite the myriad of partially overlapping datasets, more cross-country comparisons are needed covering all regions of the world and also looking at outcomes for migrants.

Where does this leave us? For the MGI, data collection will include at least 17 more countries in 2020. In addition, a local MGI pilot was conducted in 2019 in São Paulo, Brazil; Montreal, Canada; and Accra, Ghana; with many more cities in Latin America to be added soon. Information complementary to the MGI can also be found in Migration Profiles detailing migration trends in a given country.

More work remains to be done but is well underway.

This blog post is part of the International Forum on Migration Statistics (IFMS) series on the Global Migration Data Portal. The second IFMS, organized by IOM, OECD and UN DESA took place in Cairo on 19-21 January 2020. Find more information about the IFMS here.