Migration, for some, is a story of achievement, adventure and solidarity. For others, migration means danger, discrimination and loss. But sometimes the most vulnerable are those who cannot move at all and remain trapped in poverty, homelessness and violence. The story of those traveling in the migrant caravan is a combination of these scenarios.

The migrant caravan from Central America became frontline news in October 2018. Initial figures of about 3,000 migrants travelling northwards were quoted as composing the original caravan, but accounts quickly diverged as many other migrants joined the journey and population monitoring became challenging. Around the end of October 2018, about 7,200 migrants were said to participate in the caravan, while misinformation and politically driven agendas paved the way for larger estimations. On 11th of December, the Government of Mexico reported around 7,000 migrants to have arrived in Tijuana and Mexicali via the migrant caravan, after having prepared for the arrival of around 10,000 people.

The lack of reliable information prevents us from understanding the multiple drivers behind the migrant caravan, including the role of climate change and environmental degradation. Filling the data and information gap on the links between migration, environment and climate change is a step toward ensuring the safety, dignity and protection of migrants, including those in the caravan.

Migrating with Dignity in a Degrading Environment

Environmental migration is a challenge for many countries and their populations. Human mobility related to the environment can have both positive effects, when used as an adaptation measure to climate change, and negative effects, in its forced forms, by increasing inequalities. Annual displacement estimates show that, on average, 24.6 million people are forced to flee within their country every year because of disasters due to natural hazards. Projections of the World Bank point to 143 million people moving by 2050 within countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America due to the adverse effects of climate change, under a pessimistic scenario.

These figures do not however represent the full picture. We do not know the total number of people currently on the move due to slower processes of climate change. It is challenging to count people moving in the context of coastal erosion, drought or land degradation, for example. Decisions to migrate under these scenarios shape across a longer period of time and are based on various factors, not just the environment. In contrast, an earthquake, tsunami or hurricane forces people to flee almost immediately to find safety and assistance, affecting their lives, homes and livelihoods directly. Such a direct impact makes it easier to estimate the number of disaster displaced persons, but not without limitations. Nevertheless, most people move due to a combination of slow and sudden-onset factors and causes, blurring the lines between these categories.

Uncovering the Drivers of the Migrant Caravan

The multi-causality of migration is evident in Central America. Available data points to the great impact that drought has had on agricultural productivity in the Dry Corridor of Central America, affecting the availability of staple crops. The 2014-2016 drought was among the worst in the region. This year, the Honduran Government assessed that 82 percent of the maize and bean crops would be lost. By the end of August 2018, estimates of the World Food Programme (WFP) showed that 2.81 million people were struggling with food insecurity as a consequence of drought. Such figures indicate a deterioration of conditions, which could have been at the roots of the migrant caravan. However, the lack of data and evidence hinders the full understanding of the drivers behind the migrant caravan.

The wealth of knowledge on climate change and the environment in the region is not matched by similar levels of evidence on their impact on human mobility. While there is a general agreement that environmental change has negative impacts on food security and livelihoods, the extent to which this relationship shapes migration patterns is not that well defined. There are some indications on trends, nevertheless. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 1.5°C Report refers to these connections, explaining that “outmigration in agricultural-dependent communities is positively and statistically significantly associated with global temperature.” A study by IOM and WFP on migration, food insecurity and conflict in the northern countries of Central America also highlights a positive statistical correlation between migration and food security in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

Impacts of Climate Change on the Americas

Source: Ionesco, D., D. Mokhnacheva and F. Gemenne (2017), The Atlas of Environmental Migration. Routledge, London.

IOM data collected through the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) at the border between El Salvador and Guatemala shows that the main motivations of migrants participating in the caravan were: “seeking better conditions”, “violence/insecurity” and “family reunification.” It is not surprising that the environment does not appear among the drivers quoted by migrants. Environmental and climate change are most often invisible “root causes” on statistical questionnaires. They lead to a degradation of conditions that can reach the stages of food insecurity, loss of livelihoods, decreased labour opportunities, and conflict, when people have no other choice but to move.

Looking Forward

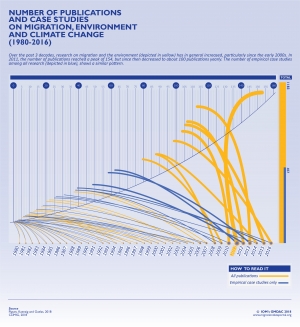

Not all hope is lost though. In recent years we have seen unprecedented advances on clarifying the links between migration, environment and climate change. International actors have been addressing this nexus at both policy and operational levels. States formally recognized that people move due to disasters, climate change and environmental degradation in the historic Global Compact for Migration, adopted just last week. The Paris Agreement for climate change delegated a task force to identify solutions for human mobility in the context of climate change. Both these policy processes have nevertheless, recognized that there is a lack of data, especially “reliable data”, which contributes to a vague discourse and unactionable decisions at national, regional and international levels.

The Global Compact for Migration calls in its Objective 2 to “strengthen joint analysis and sharing of information to better map, understand, predict and address migration movements, such as those that may result from sudden-onset and slow-onset natural disasters, the adverse effects of climate change, environmental degradation, as well as other precarious situations.”

IOM is addressing this data and knowledge gap together with several partners, including the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD), the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). A Data and Knowledge Working Group, chaired by IOM and IDMC in the framework of PDD, has been set up to look specifically into the challenges related to human mobility in the context of disasters and climate change. How this will be translated at the national and regional levels and how the adoption of the GCM will enhance such efforts is yet to be seen. Effective decision-making and actionable policies on environmental migration rest on strong evidence and knowledge. Collaboration and information sharing are therefore key to filling the data gap on environmental migration.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the blog do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers and boundaries.