Irregular migration workers defined

In the context of migration, illegal or irregular work involves three distinct concepts: foreigners, workers and jobs. Irregular foreigners are those without legal authorization to be in the country, either because they entered without inspection and did not regularize their situation (for instance, by applying for asylum), or entered legally but violated the terms of their stay by, for example, not departing when required. In some cases, the government knows of irregular foreigners, as with those who are awaiting return or those granted a temporary legal status.

Irregular workers are non-citizens employed in regular jobs without authorization to work, such as foreigners who cross borders without detection and go to work without work authorization or with false documents. Some foreigners reside legally in a country and become irregular workers because their visas allow residence but not employment, as with foreigners who violate tourist visas by going to work.

Irregular jobs or work involve employment outside the formal employment system covered by minimum wages, social security and other work-related benefit programmes. Irregular work can involve complicity between employers and workers, as when employers save money by hiring workers who do not have the tax numbers needed for payroll taxes, giving workers more take-home pay but not eligibility for benefits. Employers may prefer to hire irregular workers to pay them lower wages and to avoid paying taxes that support work-related benefit programs.

EU guidelines on migration policy define irregular migration as “the entry, and/or residence and/or employment of non-EU migrants in an EU country without the necessary documents, permits or registration.” The EU emphasizes the rights of irregular workers:

“Non-EU citizens who are found to be staying in an EU country without permission will generally be required to leave […] The rights of [unauthorized] workers should always be respected and they should receive full salaries, even if they have already left their EU host country.” (EU Commission, 2016).

The EU urges Member-State governments to “guarantee … fundamental rights and … incorporate those rights into the policies, laws and administrative practices that affect migrants in irregular situations.” (EU FRA, 2011). Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) similarly stress the rights of irregular migrant workers (see PICUM, 2017).

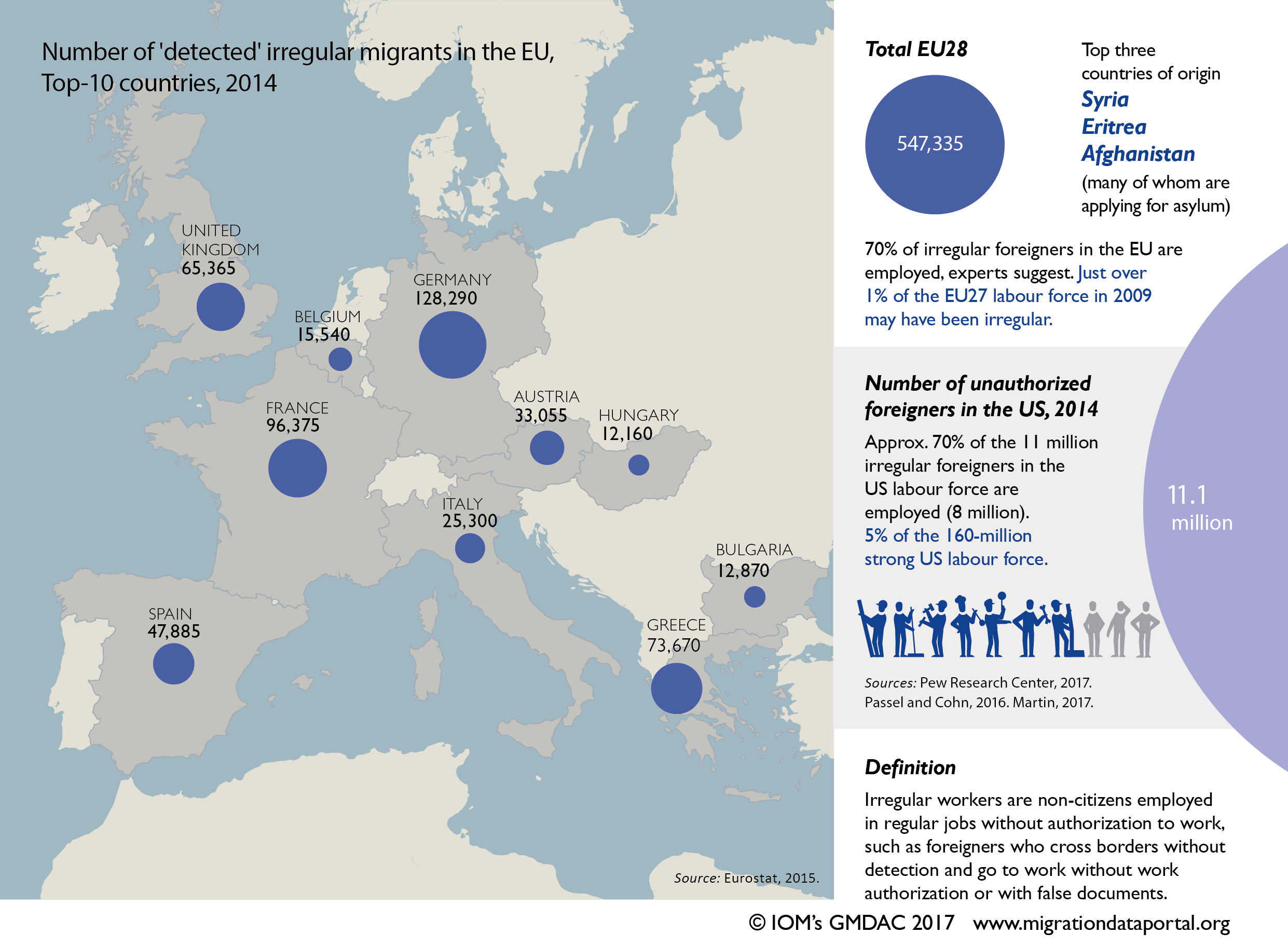

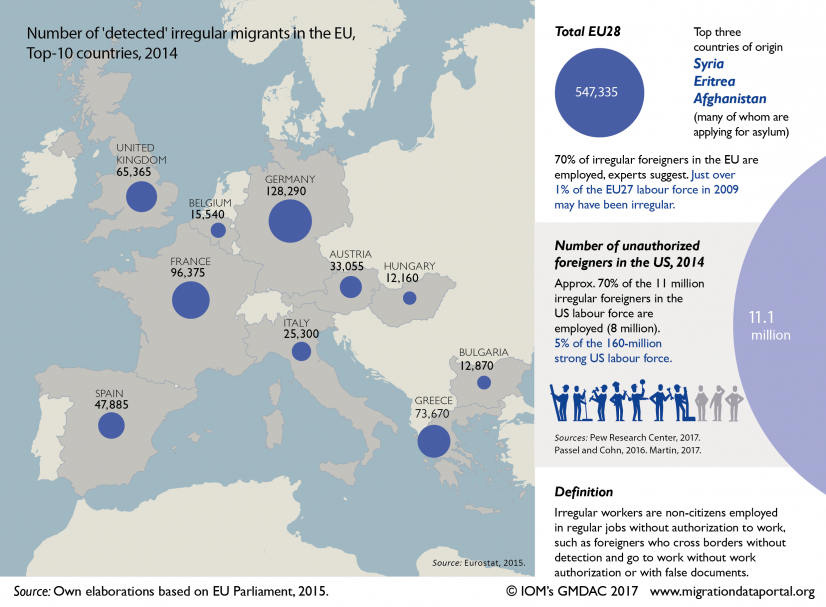

Estimates of irregular foreigners and workers in Europe

Few government agencies in EU Member States release regular estimates of irregular foreigners and workers. An EU Parliament (2015) briefing reported the number of third-country nationals “who do not fulfill the conditions for entry, stay, or residence in that member state.” Germany accounted for almost a quarter of the 547,000 irregular foreigners detected in 2014, followed by 18 per cent in France, 14 per cent in Greece, and 12 per cent in the United Kingdom (UK). Many of these irregular foreigners apply for asylum; the leading three nationalities are Syrian, Eritrean and Afghan.

Earlier estimates of the stock of unauthorized foreigners in the EU-15 countries suggested 1.8 million to 3.3 million in a total population of 390 million in 2008, or less than 1 per cent of EU-15 residents (Clandestino, 2009). The contributors in Duvell (2006) emphasize the fluidity of regular and irregular status, as when a regular student becomes irregular by working more than 20 hours a week.

European experts estimate that 70 per cent of irregular foreigners are employed (Boswell and Straubhaar, 2004). This would suggest up to 2.7 million irregular workers in the EU-27 labour force of 240 million in 2009, based on Clandestino estimates, making only 1.1 per cent of the EU labour force irregular. The share of irregular workers varies by industry, occupation and area, with concentrations in agriculture and food processing, construction and many services, from back-room jobs in hotels and restaurants to janitorial services and in-home personal care (Clandestino, 2009).

Estimates of irregular foreigners and workers in the US

The US had an estimated 11.1 million unauthorized foreigners in 2014, including 8 million in the US labour force. Some 72 per cent of unauthorized foreigners were in the labour force, and 5 per cent of the 160 million strong US labour force was unauthorized (Passel and Cohn, 2016).

The number of unauthorized workers peaked at 8.3 million in 2007, just before the 2008–2009 recession, and has been stable since due to improved conditions in Mexico, source of over half of irregular foreigners and workers in the US; tougher border enforcement has made it more difficult and expensive to enter the US in an irregular fashion. The US has another 20 million lawful immigrant workers, so that 17 per cent of US workers were born in another country.

Immigrant workers have something of an hourglass shape, concentrated at the top and bottom of the job ladder. More than 17 per cent of workers in some high-wage industries and occupations, including health care and technology, were born abroad, as were more than 17 per cent of those in low-wage occupation such as agriculture, hospitality and janitorial services. Unauthorized workers are found mostly in the bottom half of the hourglass, as farm workers, construction labourers and in back-of-the-house jobs in restaurants and hotels.

Irregular foreigner and workers under DACA and TPS

Some unauthorized foreigners are allowed to work lawfully in the US, notably the 750,000 who were granted a temporary legal status under the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. DACA recipients must have arrived in the US before age 16, been under 30 in 2012, and completed secondary school: after paying USD 465, they receive renewable two-year work and residence permits. Candidate Trump pledged to cancel DACA if elected, but President Trump has not yet cancelled DACA.

The US may grant Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to unauthorized foreigners when a natural disaster occurs in their home countries; TPS gives them permission to live and work in the US. Some 325,000 foreigners from 13 countries had TPS in the US in January 2017, including over 90 per cent from three countries: El Salvador, 195,000 or 60 per cent, followed by 57,000 or 18 per cent Hondurans and 50,000 or 15 per cent Haitians. Most of the foreigners with TPS have been in the US a decade or more.

The impact of irregular workers on local workers, employers and labour markets

How do irregular workers affect local workers, employers and labour markets? There are very few studies of the impacts of irregular workers; more common are studies of the impacts of immigrant or foreign-born workers.

One case study of irregular workers in agriculture found that they replaced unionized legal workers in a competition between employers. Labour contractors employing irregular workers offered to work at a lower price and took business away from a unionized harvesting cooperative with legal and citizen workers, prompting the cooperative to go out of business (Mines and Martin, 1984). A review of case studies of labour markets with large numbers of irregular workers found wage depression in four, including two in agriculture and in janitorial services in Los Angeles, where labour contractors hiring irregular Mexican workers took contracts to clean buildings from unionized firms hiring US Blacks (GAO, 1988: 39–40).

Most labour market studies examine the impacts of all types of migrant workers, not just irregular workers. They seek natural experiments, situations in which analysts can study labour markets after an unexpected change due to migration.

The best known migration natural experiment involved the arrival of 250,000 Cuban Marielitos in the US in summer 1980 after the Cuban government allowed anyone to leave, prompting an exodus from the port of Mariel. Half of the so-called “Marielitos” stayed in the Miami area, providing an opportunity to estimate the effects of increasing the Miami labour force by 7 per cent.

Economist David Card studied the impacts of Marielitos on Black workers and concluded that migration helped rather than hurt them because Miami employers used labour-intensive production methods to absorb the Marielitos. The influx of people also stimulated housing and other sectors, creating jobs for the newcomers and existing residents. Economist George Borjas re-examined the Miami data and found that wages for low-skilled Miami workers who did not complete high school fell from 10 to 30 per cent after the Marielitos arrived. Borjas’s sample of US workers was small, since Miami had few male, non-Hispanic high school drop outs who were US citizens.

Other papers examined what happened to broader groups of US workers in Miami, including women and teens still in school, and did not find wage depression due to Marielitos. The larger the group of native workers in which analysts try to detect the effects of newcomer migrants, the more diluted the impacts of migrants (Leubsdorf, 2017; Clemens, 2017).

A difficult task: Detecting irregular workers and balancing all workers’ rights

Irregular workers include foreign workers employed in countries without authorization, and irregular work includes jobs that do not abide by labour laws or pay taxes to support work-related benefits. Most governments have agencies and task forces to detect and remedy cases of irregular workers and irregular work. However, enforcement is difficult, in part because employers and workers generally lack incentives to inform government agencies of irregular workers and work. Nonetheless, the share of irregular workers and irregular work is small, less than 5 percent of all workers and jobs, but higher in particular industries, occupations, and areas.

All persons are entitled to fundamental human rights, and all workers are promised core labour rights in the workplace. Unions, NGOs and others aim to educate irregular workers about their rights and empower them to complain about exploitation and other violations of labour laws. Migrant advocates recognize that complaining about irregular workers and work can lead to the removal of migrants from the country, making many workers reluctant to complain.

Most governments want to protect their most vulnerable citizens and workers from “unfair” competition from migrant workers. The best way to protect local workers is to protect migrants. Ensuring that migrant workers are treated equally avoids a race to the bottom that benefits primarily employers who take advantage of irregular workers to gain a competitive edge. The challenge is to protect all workers, migrant and local, to ensure a level playing field for employers and workers.

| Boswell, C. and T. Straubhaar/th> | |

|---|---|

| 2004 | The Illegal Employment of Foreign Workers: An Overview. Intereconomics. 39(1): 4–10. |

| Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) | |

| 2016 | Occupational Employment Statistics. United States Department of Labor. |

| Clandestino | |

| 2009 | CLANDESTINO Policy Brief on the Size of Irregular Migration. |

| Clemens, M. | |

| 2017 | What the Mariel Boatlift of Cuban Refugees Can Teach Us about the Economics of Immigration: An Explainer and a Revelation. |

| Düvell, F. (ed.) | |

| 2006 | Illegal Immigration in Europe, Beyond Control? Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire. |

| EU Commission | |

| 2016 | Guidelines on EU migration policy. EU Immigration Portal. |

| EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) | |

| 2011 | Fundamental rights of migrants in an irregular situation in the European Union.. European Union, Luxembourg. |

| EU Parliament | |

| 2015 | Irregular immigration in the EU: Facts and Figures. Briefing, EU Parliament, Brussels. |

| Leubsdorf, B. | |

| 2017 | The Great Mariel Boatlift Debate: Does Immigration Lower Wages? Wall Street Journal, June 17. |

| Lott-Lavigna, R. | |

| 2017 | How many illegal immigrants are in the UK? New Statesman, February 7. |

| Mines, R. and P.L. Martin. | |

| 1984 | Immigrant workers and the California citrus industry. Industrial Relations. 23(1): 139–149. |

| Passel, J. and D. Cohn | |

| 2016 | Size of U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Workforce Stable After the Great Recession. Pew Research Center, November 3. |

| Krogstad, J. M., Passel, J. and Cohn, D. | |

| 2017 | 5 Facts about illegal immigration in the U.S. Pew Research Center, April 27. |

| Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM) | |

| 2017 | Undocumented migrant workers: Guidelines for developing an effective complaints mechanism in cases of labour exploitation or abuse. PICUM, Brussels. |

| U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) | |

| 1998 | Illegal Aliens: Influence of Illegal Workers on Wages and Working Conditions of Legal Workers. GAO, Washington, D.C. |