Wealthy migrants make up a fraction of the millions of people that move abroad each year – in 2018, just 108,000 millionaires migrated. But even if small in size, this influential group is growing year by year and wealthy migrants have a significant impact on the countries they choose, and the countries they leave behind.

Millionaire migration – how does it work?

There are around 13 million high-net-worth individuals (HNWI) globally. While the vast majority of these are millionaires, this group also includes multi-millionaires, centi-millionaires and just under two thousand billionaires. At this level of wealth, moving countries is relatively easy. Systems such as the “Einstein” EB-1 visa in the US, which allows foreigners with an “extraordinary talent” to migrate to the country are often more accessible to people in this wealth bracket.

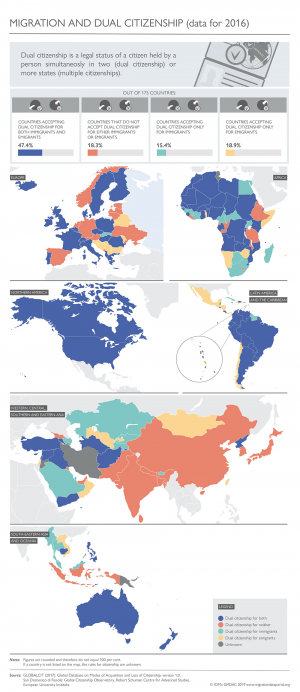

Numerous other countries, including within the European Union, allow wealthy individuals to acquire citizenship - and the right to live and work - if they make significant investments in the national economy. In most cases, applicants have to hold resident status for a certain time before applying, but do not have to physically live in the country. In 2019, the citizenship by investment programs (CIP) market was estimated to be worth USD 25 billion per year globally.

Many millionaire migrants acquire citizenship and residence rights with no intention of migrating at all. Citizenship by investment (CIP) can simply buy the options of freedom of movement, and tax benefits to use as needed.

For some, acquiring a second nationality does mean settling in a new country – this might be for political, economic or security reasons, or to escape pollution. However, lifestyle factors such as a better climate or education opportunities for children can also play a role. China was the country that lost the most HNWI migrants in 2019, with 16,000 millionaires moving overseas. In second and third place were India with 7,000 and Russia with 5,500, but thousands also migrated from Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China; Turkey; the United Kingdom; France; Brazil; Saudi Arabia and Indonesia.

CIPs have existed since the 1980s but organizations that promote transparency and government accountability have in the last few years tied CIPs to money laundering, corruption, and security issues.

What does this high-end migration tell us?

When wealthy migrants obtain a second passport, it can have a mixed impact on their country of origin. For example, China is creating millionaires at a greater rate than they are leaving, so the financial impact is neutralised. Elsewhere however, high levels of millionaire migration are often an indication of the situation in a country shifting. New World Wealth’s 2020 Global Migration Review says “HNWIs are often the first people to leave — they have the means to leave, unlike middle-class citizens.”

It follows then, that countries on the receiving end of millionaire migration are often safe and stable, with growing economies, business opportunities, good schools and strong healthcare systems. Estimates suggest that Australia has been the most popular destination for the past five years, accepting 12,000 millionaire migrants in 2019, closely followed by the US with 10,800. Other popular 2019 destinations included Switzerland, Canada, Singapore, Israel, New Zealand, UAE, Portugal and Greece, Malta, Monaco, the Republic of Mauritius, and the Caribbean.

English-speaking countries are popular, as many millionaire migrants speak English as a first or second language. But lifestyle factors are not the whole story. For example, the lack of inheritance tax in Australia is also thought to play a key role in the country’s appeal to the wealthy.

Freedom of movement amid a global pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has also had an impact. In New Zealand CIP programs cost USD 1.9-6.5 million, but have been in high demand due to the country’s successful management of the health crisis. In smaller countries such as those in the Caribbean, where CIP programs cost around USD 100,000-150,000, demand is also rising as they have been hit less hard by the pandemic than countries with large populations. Smaller towns and cities with good access to nature where the wealthy can escape future crises are also expected to become more popular.

Provisional estimates suggest that the number of millionaire migrants may have fallen overall in 2019 compared to previous years, but any downward trend is unlikely to last. As the world’s countries closed their borders, having dual citizenship was about more than money or lifestyle management – it also bought the right to international movement. Could having a second passport become the ultimate status symbol: exclusive access to freedom and security, in an increasingly unpredictable world?