Migrants’ exposure to abuse, exploitation, human trafficking and other human rights violations is well documented along many migration routes. Especially, when looking at the Central Mediterranean Route, there is a significant amount of evidence. The frequency and scale of violence and abuses suffered by migrants on the journey, particularly in Libya, has been documented by the media, practitioners, academic studies as well as by advocacy and UN reports (OHCHR and USMIL, 2016, Amnesty International, 2016; IOM, 2017; Council of Europe, 2019).

Yet, synthetizing the most frequent traits of this journey to Europe, the profiles of those more at risk of experiencing abuse and exploitation and how these change over time is difficult, because it requires, at least, to choose summary indicators to proxy multi-dimensional individual and journey’s aspects and to have the capacity to consistently collect information and data over an extended period of time.

This is what IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) Flow Monitoring Surveys in Europe try to achieve, by collecting quantitative and qualitative information from migrants arriving by sea and by land at key and targeted areas to several European countries since 2016. Since then, DTM Europe has collected over 36 thousand surveys with migrants travelling along the Eastern, Central and Western Mediterranean migration route, updating profiles for the main nationalities identified and gathering systematic evidence on a selected list of exploitative practices and abuse that migrants experience while traveling towards Europe.

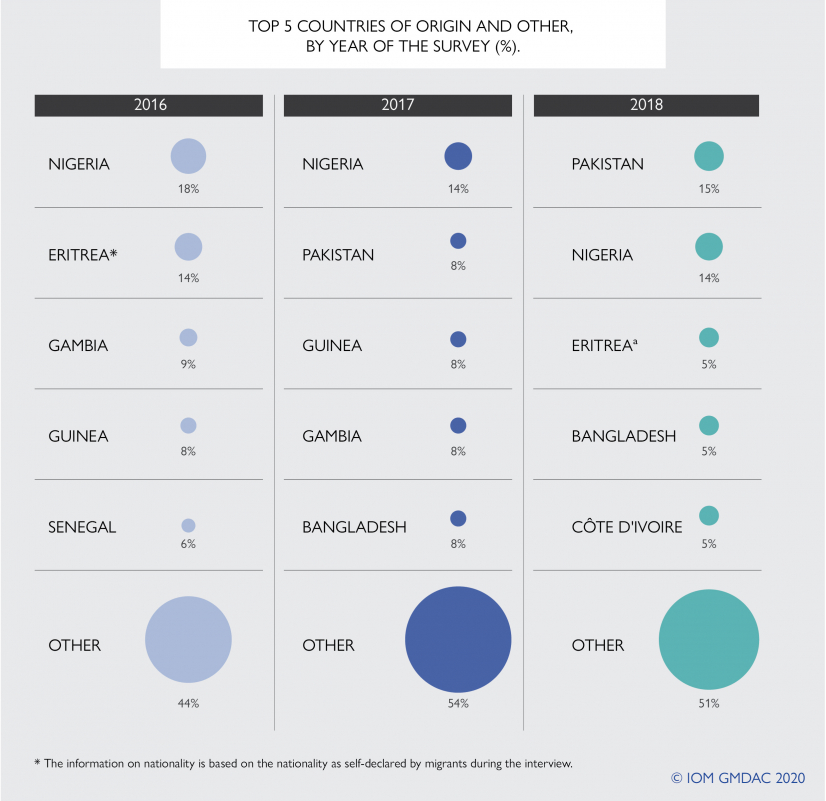

The chapter "Vulnerability to exploitation and abuse along the Mediterranean migration routes to Italy" by DTM in the recently published Migration in West and North Africa and across the Mediterranean: trends, risks, development, governance (2020) looks in particular at the surveys gathered in Italy between 2016 and 2018 from 12 thousand men, women, boys and girls of 55 different nationalities, that arrived in Europe after travelling by sea through the Mediterranean.

Overall, a share between 66 and 77 per cent of respondents answered yes to at least one of the four direct questions on exploitation and abuse included in the survey (having worked without payment, having been forced to work, having been held against their will, having been offered an arranged marriage). Moreover, a question on physical violence was included in 2017: although physical violence as a single experience is not considered among the indicators of human trafficking or exploitation, its presence – in combination with other indicators – points to control mechanisms that are typical of individuals suffering from exploitation and who might be victims or at risk of human trafficking. Indeed, more than two thirds of the sample since 2017 reported having had direct experience of physical violence (beatings with sticks, burnings, stabbings and bullet wounds, use of electric wires, deprivation of food and water etc.).

Our analysis suggests that younger and male respondents are more vulnerable to direct experiences of unpaid and forced work, and of being held against their will. The probability of reporting at least one of these experiences increased since 2016 and increased more for those traveling through Libya and for those originating from Western Africa and from the Horn of Africa. Also, although women were less likely than men to report forced or unpaid work or to be held against their will, results relative to indirect experiences of sexual violence with accounts of observed threats and perpetrated violence on others suggest that it is essential not to overlook the specific types of violence and abuse most commonly reported by women and girls.

Longer journeys are systematically associated with more stops, different modes of transportation at each leg and increased chances of finding oneself in need of more money to be able to move forward. The need to earn and save money along the journey puts migrants at risk of becoming victims of exploitative labour conditions and of having more dangerous travel arrangements, especially in countries bordering Europe. Time spent in travel also depends on unforeseen stops, such as various forms of detention-like conditions, being forced to stay in a confined space to extract labour or money before being allowed to move again, which increase the risks for migrants travelling to Europe even before trying to cross the Central Mediterranean sea, left with a very reduced search and rescue presence from the European side over the last 2 years.

If that was true in a pre-COVID-19 era, the reinforced controls in origin, transit and destination countries are certainly making the journey more difficult for those traveling amidst a pandemic. The pandemic has widely affected global mobility in the form of various travel disruptions and restrictions, imposed by authorities to curb the spread of the virus since late February 2020 (see Schöfberger and Rango in the same volume, 2020). This has impacted the number of departures and arrivals. Since then, after a sudden drop in arrivals in the first half of 2020, arrivals to Italy grew by more than 3 times in the first three quarters of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. COVID-19 has put an additional layer of risk on those traveling towards Italy and has potentially made the overall disembarkation and distribution mechanism more complex.

Operational data as those provided by DTM have proven particularly crucial in enhancing the understanding of migration dynamics and profiles of migrants traveling along the Central Mediterranean route, given the limited availability of migration data from official sources in all countries involved, including those of destination. As discussed by Fargues in the same volume (2020), “further strengthening data collection and dissemination on outward and inward international migration (…) would help understanding of the dynamics playing out at regional levels”.

Arrivals to Italy reached a record low in 2019 when compared to the previous 10 years, and even in 2020 the number of African and Asian migrants reaching Italy and Europe through the Mediterranean is small compared to the last decade and to the size of intra-regional migration movements in Western Africa, the Middle East or the Horn of Africa. Only a comprehensive account of migrants’ conditions while traveling along the Central Mediterranean route can help us understand how migrants can weigh the possible positive and negative outcomes of their migration decision. Hence, the conditions of travel and the lived experiences of many of those finally reaching Italy departing from Libya after long and perilous journeys calls for enhanced assistance, which should be able to recognize and respond to the multi-layered perils that men, women and children traveling across the Mediterranean have endured.