Migration data in Eastern Africa

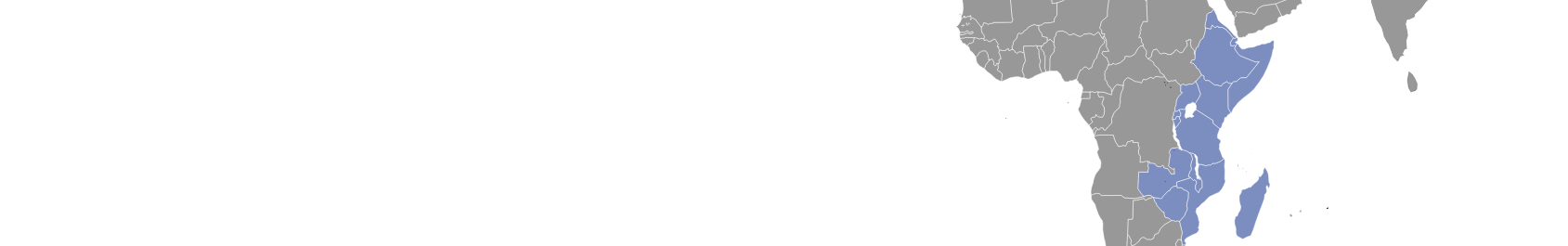

Eastern Africa has historically been part of global migration and trade networks and continues to play an important role in both. The geographic sub-region1spans a total of 18 countries, ranging from Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan and Uganda in the west to Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, Kenya and Somalia in the east to Malawi, Mozambique, the United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe in the south and the island nations of Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius and Seychelles2, each with its unique migration pattern and profile.

Home to an estimated population of 445 million, the sub-region hosted 7.7 million international migrants at mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020a). The sub-region hosted more than 4 million refugees and asylum seekers in 2023 (UNHCR, 2024).

IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) observed 950,000 movements in the region in 2022 (IOM, 2023). Of these, over 46 per cent were intending to travel eastwards to the Arab Peninsula from the East and Horn of Africa (EHoA)3 region and over 2 per cent northwards to northern Africa and Europe.4 The region is characterized by developmental challenges and shifting demographics as populations grow and migrate towards urban centres, other parts of the region or beyond. Migration drivers include poverty, conflict and environmental events such as droughts and floods.

Recent trends

- Uganda (1.7 million), Ethiopia (1.1 million) and Kenya (1.1 million) were estimated to be the three countries hosting the highest number of international migrants in the region at mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020a).

- The number of people in need of humanitarian assistance in the region reached a record high of 43.8 million, representing 28 per cent of the regional population. This increase was driven by a combination of conflict, climate events, and macroeconomic challenges (IOM, 2023).

- The longest and most severe drought critically affected parts of Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. This drought largely impacted agropastoral communities, devastating their main sources of livelihood and straining their resilience to climate change (IOM, 2023).

- Reasons such as a lack of economic opportunity and the expectation to find better livelihood opportunities elsewhere are two of the major migration drivers in the region (IOM, 2023).

- Political tension, conflict and natural disasters are at the root of most of the region’s large refugee and displaced populations. Conflict and violence persisted particularly across Ethiopia, Somalia, and South Sudan. The signing of the northern Ethiopia peace deal in early November 2022 brought hope for reduced tensions and unhindered humanitarian access, although tensions continued in other parts of Ethiopia (IOM, 2023).

-

By the end of 023, the sub-region hosted 4.4 million refugees and asylum seekers. Uganda (1.6 million),Ethiopia (1 million) and Kenya (690,000) had the highest caseloads of refugees and asylum-seekers in the sub-region (UNHCR, 2024).

-

A staggering of 10.3 million people remained internally displaced in the region at the end of 2023, the majority due to conflict (8.5 million). The largest number of IDPs due to conflict lived in Somalia (3.9 million), Ethiopia (2.9 million) and South Sudan (1.1 million) (IDMC, 2024).

-

Around 46 per cent of the migratory movements documented during 2022 in the East and Horn of Africa were towards or within the region (on the Horn of Africa route). Another 46 per cent were eastwards along the Eastern Route to the Arab Peninsula, in particular to and from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Yemen (IOM, 2023).

-

Remittances play an important role in many countries in the subregion. In Comoros (21%), South Sudan (16%) and Somalia (15%) remittances accounted for more than ten per cent of the countries’ GDP.

Past and present migration trends

Situated on the Indian Ocean, the Horn is the continent’s gateway to Asia, harbouring deep historical ties to the Middle East, China and India that continue to manifest themselves in investment and trade deals today. Migration to and from the region has historically occurred along similar routes, particularly to and from the Middle East and India. During the colonial era, the region was colonized by the UK, Italy, Belgium and Germany; a small number of nationals of these countries still live in their respective former colonies.

800s-1500s AD

- Earliest evidence of Arab migrants in Eastern Africa dates back to 830 AD (Lodhi, 1994).

- By 1300 AD, Islam was a common religion along the East African coastline, with Arabic being the commercial language spoken in many coastal areas (ibid.).

- Swahili culture was well established along the East African coastal belt through political and trading networks with the northern and eastern areas of the Indian Ocean by the 1500’s (ibid.).

1800s-1960s

- Well over a million East Africans were sold by slave traders to Middle Eastern countries, Arab kingdoms, Persia and countries further East (Campbell, 2008).

- Even though Asians have lived on the east coast of Africa for around 2,000 – 3,000 years, the majority of Asians (primarily from India and Pakistan) arrived in Eastern Africa as indentured servants to the British in the nineteenth century (Forster et al., 2000). Many Asians decided to migrate to Eastern Africa to escape widespread poverty and famine in India and for employment opportunities such as building the Ugandan railway. The South Asian population in British East African territories thus grew from around 6,000 in 1887 to around 366,000 by the end of the British colonial rule (Dickinson, 2012). A large number of Indian diaspora members still reside in Eastern Africa, particularly in Mauritius, Kenya, Mozambique, the United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda, Madagascar, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Seychelles and Malawi.

- In the wake of growing nationalism following political independence, Asians in Eastern Africa were gradually pushed out of both rural and urban areas. In Kenya and Tanzania, the pushback was less severe in order to avoid economic disruption as Asians continued to occupy a significant proportion of key technical, managerial, administrative and other professional jobs. In Uganda, following a military coup, Idi Amin capitalized on racialized antipathy towards Ugandan Asians and announced the expulsion of all Asians from Uganda in August 1972. East African Asian refugees migrated across the world, in particular to the United Kingdom. By 1973, around 103,588 Asians had arrived in the UK fleeing political and economic persecution in Britain’s East African colonies (Mattausch, 1998).

1990s – Present

Today, mixed migration5 and labour migration are key features of the migration landscape in Eastern Africa. Several intra-African routes are bidirectional, indicating a significant prevalence of temporary or circular labor migration. 82 per cent of the migrant workers in Africa in 2019 were in East Africa (4.1 million), West Africa (4.3 million) and Southern Africa (3.5 million), 10 per cent in Central Africa (1.5 million) and Northern Africa hosted 8 per cent (1.2 million) (GMDAC calculations based on African Union Commission and JLMP partners, 2021).

In Africa, as in the rest of the world, most refugees remain near to their countries of origin, as they frequently relocate to neighboring countries (African Union, 2024).

By the end of 2023, there were around 4.5 million refugees from Eastern Africa globally, the majority hosted in neighbouring countries, and 4 million refugees hosted in the subregion (UNHCR, 2024). Additionally, a staggering of 8.5 million people were internally displaced by conflicts in the region and 1.8 million people due to disasters at the end of 2023 (IDMC, 2024). There are currently several forced displacement situations in the region, each with its own unique characteristics and spill-over effects from and into neighbouring countries.

The ongoing violence, a deteriorating security situation and food insecurity in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo has led to significant mixed cross border movements of refugees, returnees and third-country nationals into its neighbouring countries, especially into Uganda and South Sudan (UNHCR, 2024).

- Ethiopia: Ethnic tensions, political persecution and environmental disasters such as drought and soil degradation have forced millions to flee their homes in recent years. Nearly 2.9 million people due to conflict and 880,000 people due to disaster remained internally displaced at the end of 2023 (IDMC, 2024). Ethiopia hosted also the second highest refugee population in the subregion with nearly 980,000 refugees (UNHCR, 2024).

- Somalia: Political insecurity and environmental factors including drought and famine continue to force Somalis to leave their homes. With nearly 3.9 million internally displaced persons due to conflict, Somalia had the highest number of internally displaced persons due to conflict in the subregion at the end of 2023 (IDMC, 2024). Additionally, more than 842,000 people were displaced across borders as refugees (UNHCR, 2024).

- South Sudan: Movements within and from South Sudan are mainly driven by civil war and critical food insecurity. More than half (2.3 million) of the sub-region’s refugees globally originated from South Sudan at the end of 2023 (UNHCR, 2024). Additionally, 1.1 million people remained internally displaced at the end of 2023 due to conflict and more than 560,000 due to disasters (IDMC, 2024). South Sudan hosted also more than 380,000 refugees, the majority (360,000) originated from its neighbouring country Sudan (UNHCR, 2024).

- Kenya: Northern Kenya experienced significant displacements in recent years due to severe drought affecting pastoralist communities. More than 130,000 persons remained internally displaced due to disasters at the end of 2023 (IDMC, 2024). Kenya hosted the third highest refugee population in the subregion with nearly 540,000 refugees (UNHCR, 2024).

- Uganda: Uganda hosted the highest refugee population at the end of 2023 with nearly 1.6 million refugees. The majority of refugees originated from South Sudan (920,000), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (500,000) and Somalia (40,000) (UNHCR, 2024).

Migration corridors

The mixed movements of displaced populations, migrant workers and other people on the move within and from the region can be characterized along four main corridors (IOM, 2023). In 2022, 92 per cent of all movements tracked in the region were detected along the Horn of Africa and Eastern corridor (ibid) :

- Horn of Africa Corridor- captures movements towards and within the Horn of Africa8.

- Eastern Corridor- used by migrants moving between countries in the EHoA region and towards countries on the Arab Peninsula, particularly the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The corridor is one of the busiest and riskiest in the word, used by hundreds of thousands of migrants, most of whom travel irregularly and frequently depend on smugglers to help them transit.

- Southern Corridor runs from the EHoA region to Southern Africa, particularly South Africa. Compared to other migrant flows in the region, this route remains largely understudied with few current and comprehensive data available.

- Northern Corridor - refers to movements from the EHoA region to the North of Africa, Europe and North America.

Data sources

The following data sources provide both regional and national-level information on migration patterns and migration-related challenges in the Eastern Africa sub-region.

UN sources

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) - the Population Division regularly publishes data on the international migrant stock by country, the latest being for mid-year 2019. The published estimates draw on official national statistics on the foreign population residing in each country. Available data are:

- Migrant stock by sex and country; total population by area, region and country; migrant stock as a percentage of total population; annual rate of change of migrant stock by area, region and country

- Estimated refugee and asylum seeker stock by area, region and country

- Total migrant stock by destination and origin; total migrant stock by sex, destination and origin.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) - Established in early 2018 at IOM’s Regional Office for the East and Horn of Africa (EHoA), the Regional Data Hub (RDH) aims to support evidence-based, strategic and policy-level discussion on migration through a combination of initiatives, including: strengthening data collection capacity to monitor population mobility; building information management capacity; conducting regional research and analysis on mixed migration topics and enhancing data dissemination and knowledge sharing across programmatic and policy-level stakeholders; and technical development initiatives aimed at governmental stakeholders to strengthen migration data at the national and regional levels. In particular, the RDH publishes regular mixed migration updates of data collected through IOM’s various data collection modules in the region. These include the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM), registration data collected at IOM's Migration Response Centres as well as profiles of other populations on the move (IOM’s latest regional products can be found here). IOM's DTM is designed to track and monitor displacement and migration flows by collecting information on the volume and basic characteristics of populations transiting through established Flow Monitoring Points (FMPs). Regional DTM updates can also be found on the global DTM website.

The Regional Migration Data Hub for Southern Africa (RMDHub), established by IOM in partnership with SADC Member States and other key stakeholders, serves to generate information on migration in Southern Africa through data collection, collation and analysis. This includes statistics gathered through Flow Monitoring Surveys. Data published by IOM on SADC Member States is published on this portal, and it is the result of the engagement of the IOM Regional Office from Southern Africa with key stakeholders in SADC Member States.

UNHCR’s Refugee Population Statistics Database provides statistics on refugees and asylum seekers for the region. This interactive dashboard allows users to filter by year, country of asylum, country of origin and type of persons of concern (including refugees, asylum-seekers, returned refugees, internally displaced persons, returned IDPs and stateless persons). Demographic breakdowns (age and sex) by year and country of asylum can also be viewed.

UN OCHA Regional Office for Southern and Eastern Africa (OCHA ROSEA) - publishes periodic humanitarian outlooks and snapshots offering key humanitarian indicators, including displacement trends and numbers, for Horn of Africa and Great Lakes countries. The organization provides context to observed migration patterns and dynamics that can help identify existing and potential drivers of migration.

Academic sources

Research and Evidence Facility (REF) of the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa - conducted by a consortium of researchers from SOAS at the University of London, the University of Oxford and Sahan Research, REF produces policy-relevant knowledge and evidence to foster a better understanding of regional migration dynamics, cross-border economies, drivers of displacement and governmental migration management systems and capacities in the region. REF publishes regular research and working papers on migration-related topics in the region.

United Nations University (UNU-MERIT) - Migration and Development are among UNU-MERIT’s key focus themes. They have published a series of research papers related to migration in the region, most recently a comprehensive Study on Migration Routes in the East and Horn of Africa and seven migration profiles for the region: Djibouti; Eritrea; Ethiopia; Kenya; Somalia; South Sudan and Uganda. The study provides an overview of regional migration trends, drivers of displacement by displacement type, intra-regional policy responses to migration and relevant migration-related policies at the national level by country.

Other sources

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) - provides data on internal displacement crises across the world. Its country profiles offer data on IDP stock and flow numbers, disaggregated by drivers of displacement. The profiles also provide an overview of conflict and disaster events that triggered migration, an analysis of the drivers of internal displacement and a look at country-specific displacement patterns. Eastern African country profiles can be found at the following links: Burundi, Comoros, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, the United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

REACH Initiative - a humanitarian information management organization currently operating in Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Uganda. REACH conducts periodic, humanitarian needs assessments and publishes reports that include updates on population movements, displacement and the humanitarian context.

Samuel Hall - a think tank based in Nairobi conducting research on migration and displacement in several regions including East Africa.

Mixed Migration Centre - formerly known as the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS), provides largely qualitative data on irregular migration trends in the East and Horn of Africa on a regular basis. In addition to monthly summaries by country, the centre publishes thematic reports.

Institute for Security Studies - publishes occasional reports related to migration in the East and Horn of Africa region with a focus on security studies.

Data strengths and limitations

Although the accessibility and availability of migration data on stocks have improved over the years, data on flows and internal migration continue to be limited in the region (as elsewhere).

Due to differences in definitions of migrants and the timing of national censuses, estimates on migrant stocks in countries are based on extrapolation and interpolation. For countries in the region with no data, such as Somalia, UN DESA estimates the data by imputation from ‘model’ countries that are geographically close and use similar criteria for counting migrants (UN DESA, 2020b).

As listed in the previous section, population movement tracking systems provide rough estimates of forced and mixed migration flows in the region. However, they are often incomplete due to insufficient capacity, inability/unwillingness of individuals to provide information, limited access to areas with political instability and political pressures (Sarzin, 2017).

Patchy availability of comparable micro- and macro-level data also limits studies on the effects of development on migration and vice-versa.

Regional stakeholders and processes

African Union (AU) – The first iterations of migration-relevant intra-African commitments occurred in 1979 under the AU’s precursor – the Organization of African Unity (OAU) – which called for the preparation of an African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (entry into force, 1986). It was the first Africa-wide human rights instrument which stipulated that every individual should have the right to freedom of movement within the territory of a country and the right to leave and return to his/her own country. In 1991, the AU adopted the African Economic Community (Abuja Treaty), which codified the right to free movement of persons in Africa into a legally binding commitment for Member States (Article 43).

The AU formulated migration frameworks, such as the African Common Position on Migration and Development (ACPMD) and the Migration Policy Framework for Africa (MPFA), both of which were adopted in 2006. The MPFA recognizes that mixed migration is an essential component of the AU’s economic and political landscape and that cross-border movements represent vital livelihood and coping strategies in the face of economic, humanitarian and ecological disasters. In 2018, the AU revised the MPFA and adopted a Plan of Action (2018-2030) in Addis Ababa.

The AU’s vision for Africa, Agenda 2063, includes goals and targets related to the free movement of persons within RECs and Member States and a continent-wide visa waiver programme for intra-African travel. Adopted in 2015, the First Ten-year Implementation Plan of the Agenda 2063 included the creation of a Pan-African passport and the free movement of people. The common, biometric African passport was launched by the AU Assembly in 2016 to facilitate the free movement of people within Africa, and in January 2018, the Union adopted the Protocol on Free Movement of Persons in Africa currently ratified by four countries and will enter into force upon deposit of the 15th instrument of ratification (see here for the current list of ratifications). If implementation challenges are overcome, the Protocol will foster greater intra-Africa trade and labour mobility. To date, a number of African states, including Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda and Ethiopia, have implemented or declared their intent to implement visa liberalization policies for African visitors.

Other AU policies and instruments related to migration include:

- 1969 Convention Governing Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (1969);

-

The Protocol on the Amendments to the Constitutive Act, which, inter alia, invites the African Diaspora, an important part of the continent, to participate in the building of the African Union (AU) Plan of Action on Employment Promotion and Poverty Alleviation (2004) - calls on Member States to harmonize their labour and social security frameworks, develop labour inspectorates to ensure that private agencies engaged in international recruitment adhere to national labour standards and provide equal treatment to migrant and national workers;

- Ouagadougou Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Human Beings Especially Women and Children (2006) - aimed at developing co-operation, best practices and mechanisms to prevent human trafficking between the European Union and the AU;

- AU Social Policy Framework (2008) - promotes collaboration on social security schemes to ensure access and transfer of social security benefits to migrant workers;

- AU Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) (2009) - obliges states to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to IDPs within their territory and codify such assistance into their domestic laws and legislation;

- The African Union Model Law for the Implementation of the African Union Convention for the Protection of and Assistance to IPDs in Africa (January 2018)

- AU Minimum Integration Programme (2009) – re-emphasized the priority objective of implementing free movement of persons in the AU as well as the need to foster economic integration;

- Diaspora Summit Declaration (2012);

- Convention on Cross-Border Cooperation (Niamey Convention) (2014) - calls for the promotion of cross-border cooperation at local, regional and sub-regional levels;

- AU Horn of Africa Initiative (2014) - launched as a platform for dialogue and exchange of information on smuggling and trafficking;

- Joint Labour Migration Program (2015) - aimed at enhancing labour migration governance by facilitating the free movement of workers as a means of advancing regional development and integration;

- AU Humanitarian Policy Framework (2015) - provides a framework for protection and assistance in mixed migration;

- Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (March 2018) - provides a framework of movement of business-persons in the context of Trade in Services;

- Statute of the African Institute of Remittances (2018) - has a mandate to improve remittance data, legal and regulatory frameworks and leverage the potential impact of remittances on social and economic development.

- The Pan African Forum on Migration - an annual forum of AU member states and Regional Economic Communities (RECs), provides a platform for an all‐inclusive, open, comprehensive dialogue on migration issues among Member States, RECs, partners and relevant stakeholders with the aim of reaching a common understanding on the critical migration agenda in the continent.

East African Community (EAC) - adopted the Common Market Protocol in 2010, providing for the free movement of goods, capital, services persons and labour and establishing the rights of workers migrating within the community. The protocol also aims at harmonizing the issuance of national IDs, a qualification recognition system, and streamlining labour and social security policies. Although the EAC has fostered some degree of mobility in the region, the full implementation of free movement remains a challenge as movement remains subject to national legislation (IOM, 2018).

Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) - launched the Regional Migration Policy Framework (RMPF) in 2012 under its Migration Program to promote migrant well-being, streamline regional and national migration management in the region and support its Member States’ efforts to address migration-related challenges holistically through recommendations and guidance on policy and legislation. To facilitate the operationalization of the RMPF, IGAD developed the Migration Action Plan 2015-2020 (MAP) comprising 12 strategic priorities, including: improving labour migration management, building and fostering existing national data systems on migration, facilitating the free movement of people in the IGAD region and supporting the cross-border mobility of pastoralist communities and families.

The IGAD Regional Consultative Process on Migration (RCP) has the overall objectives of (1) facilitating dialogue and regional cooperation in migration management amongst IGAD member states by fostering greater understanding and policy coherence in migration, and (2) strengthening regional, institutional and technical capacities to implement the migration policy framework for Africa and other AU/IGAD policies on migration.

National Coordination Mechanisms on Migration (NCMs) – government-led inter-agency coordination platforms tasked with discussing migration issues and facilitating cooperation among relevant stakeholders with migration-related mandates, thereby contributing to better migration management and governance. Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan currently have active NCMs, while Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan have widened their membership in existing coordination platforms but have not yet established active NCMs. Since mid-2019, IGAD Member States acknowledged that existing migration data are fragmented across many government agencies and are rarely collected for statistical purposes. That led to the commitment to establish a regional technical working group (TWG) to facilitate the harmonization, comparability and accessibility of migration data building on existing good practices from other regions on the continent and intra-REC cooperation in the Eastern Africa region. This TWG will facilitate capacity development interventions on data collection and analysis of broader mobility issues, mainstream migration into development plans and national data collection efforts, and enable migration data exchange in the region.

The IGAD Regional Guidelines on Rights Based Bilateral Labour Agreements, were adopted by all IGAD Member States at the Ministerial Conference on Labour, Employment and Labour Migration in IGAD Region in October 2021. The Guidelines' main area of interest is labor migration from the Middle East to the IGAD.

The Munyonyo Declaration on Durable Solutions for Refugees in the East and Horn of Africa has been signed by Ministers in charge of refugee affairs from Member States of the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and Partner States of the East African Community (EAC) in May 2023. The declaration addresses areas of violence and conflicts, natural disasters, the negative effects of climate change and protection. The declaration was endorsed by 11 Member States.

Further reading

| African Union Commission and JLMP partners (ILO, IOM, UNECA) | |

| 2021 | Report on Labour Migration Statistics in Africa (3rd edition). Addis Ababa. |

| Eastern African Community (EAC) | |

| 2022 | East African Community International Migration Statistics Report (1st edition). Arusha. |

| International Organization for Migration (IOM) | |

| 2024 | Africa Migration Report (Second edition). Connecting the threads: Linking policy, practice and the welfare of the African migrant. IOM, Addis Ababa. |

| 2023 |

East and Horn of Africa overview of missing migrants data (2022). Displacement Tracking Matrix in the East and Horn of Africa. |

| 2023 | A Region on the Move 2022: IOM Regional Office for the East and Horn of Africa, Nairobi. |

| n.d. | Displacement Tracking Matrix in the East and Horn of Africa. |

| Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) | |

| n.d. | Quarterly mixed migration updates: East & Southern Africa. |

| Research and Evidence Facility (REF) | |

| n.d. | Research reports, summaries, policy briefings and working papers. EU Trust Fund for Africa (Horn of Africa Window) Research and Evidence Facility, London and Nairobi. |

1 As defined by the UN Statistics Division.

2 Comoros, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and the United Republic of Tanzania are considered Southern African States as they are among the members of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Data in these countries are explored in detail in the SADC regional data overview page.

3 IOM’s regional designation of the East and Horn of Africa (EHoA) covers 10 countries: Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania.

4 This figure is only indicative of the number of migrants exiting the region, as flow monitoring activities have only limited coverage (DTM East and Horn of Africa Region).

5 Mixed migration is a complex, relatively new term and thus slightly differently defined by various entities. According to IOM, the principal characteristics of mixed migration flows include the irregular nature of and the multiplicity of factors driving such movements. Mixed flows are defined as, “People travelling as part of mixed movements have varying needs and profiles and may include asylum seekers, refugees, trafficked persons, unaccompanied/separated children, and migrants in an irregular situation.” (IOM, 2019)

6 The Democratic Republic of Congo is also a Member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

7 This figure is based on consultations between the PRMN and DTM specialists, and has been endorsed by the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) and by the Government of Somalia.

8 The Horn of Africa is comprised of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia.

9 The Flow Monitoring Registry (FMR) aims at capturing quantitative data about volumes of migrants, nationality, sex and age disaggregated information, origin, destination and observable vulnerabilities. This is done by enumerators deployed at locations of high mobility through key informant interviews. More information is available here.

10 IOM DTM. The information is based on the nationality declared by migrants, as reported by the Italian Ministry of Interior. The Italian authorities provided full disaggregated data by nationality, sex, and age up to April 2018. Since then, data have been provided on top 10 nationalities only. Eritreans are the second national group by number of arrivals.

Back to top