Two salient traits characterized this evolution. The first is that regional dialogue and national policies have turned from discussing almost exclusively the regulation aspects of the migration processes to a broader discussion on migrants’ rights and their integration in host countries. The second is the iteration between agreements and dialogues that take place at a regional level and changes in norms, regulations, procedures and policies that take place at a national level. Many countries in the region have changed their legislation on migration according to international standards that protect the rights of migrants. These improvements involve considering not only immigrants, but also the rights of nationals living abroad as well as returnees.

As part of this process, some countries have enhanced their institutional capacities by creating national (and local) level inter-institutional mechanisms for managing migration. Consequently, most countries in the region have improved migration services, facilitate access to residency permits, and favor educational transfers and the portability of social security rights.

These improvements have even proven to be helpful in some countries to manage the arrival of immigrants, refugee and asylum seekers from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. In fact, in 2018 South American governments from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay, and also from Costa Rica, Mexico and Panama, signed the Quito Declaration on Human Mobility of Venezuelan Citizens in the Region, an agreement on how to manage in a coordinated way the migratory crisis of Venezuelan citizens.

Partly, these agreements were facilitated by a previous dynamic of regional dialogues in which migration and the rights of migrants were at the core. The Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR for its Spanish initials), the Andean Community (CAN), the South American Migration Conference and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) are important examples of these regional dialogues.

Background: The MERCOSUR residency agreement

At the turn of the twenty first century, regional agreements started to treat migration in a more consistent manner and with a human rights approach.

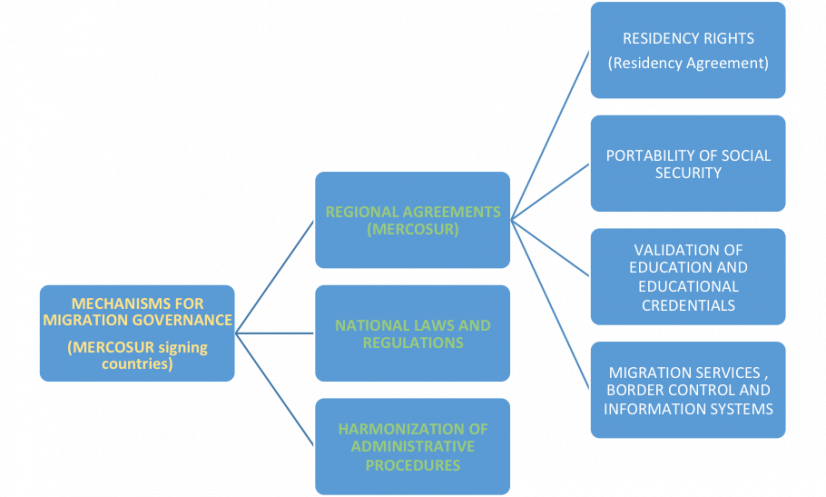

The MERCOSUR residency agreement specifically focused on protecting human rights and promoting similar legal standards and control mechanisms for their citizens. Since then, the governance of intraregional migration and the protection of migrants’ rights has considerably improved through a series of mechanisms shown in Figure 1, that is, access to residency rights, improving economic integration through access to formal jobs, recognition of educational credentials, portability of social security rights and access to social services (health and education).

Mercosur agreements: mechanisms to improve mobility conditions and migrants’ rightsSee OIM (2018) Evaluación del Acuerdo de Residencia del MERCOSUR y su incidencia en el acceso a derechos de los migrantes. Cuadernos Migratorios N 9. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/estudio_sobre_la_evaluacion_y_el_impacto_del_acuerdo_de_residencia_del_mercosur.pdf

Source: IOM, 2018.

Note: Based on IOM's Evaluation of Mercosur's Residence Agreement and migrants' access to their rights. Cuadernos Migratorios N 9.

The MERCOSUR Residency Agreement was originally signed in 2002 but effectively entered into force in 2009. Argentina, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay were part of the agreement and later Colombia, Ecuador and Peru also signed. It establishes common rules for the processing of residence permits, simplifying and harmonizing the requirements. Holding a residence permit (temporary or permanent) implies access to the right of entering, leaving, being mobile, and remaining freely in the territory of the receiving country, enjoying the right to health, education, family reunification, and work, and to freely transfer remittances. Thus, it provides equality of civil rights and the social, cultural and economic freedoms of nationals of the receiving country.

Also, since the turn of the century, most South American countries –Argentina, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Uruguay— have changed their national migratory laws, turning them more respectful of migrants’ rights and adapting their frameworks to the current situation. Most countries have improved the institutional capacity of migration offices, facilitating access to residency permits, border controls and sharing of information.

Source: Various data sources from the Argentine government, 2009-2018.

Note: IOM South American Regional Office collected statistics from several national migratory offices.Based on data from Argentina: Dirección Nacional de Migraciones; Brazil: Ministério da Justiça and Departamento de Polícia Federal; Bolivia: Dirección General de Migración; Chile: Dirección de Extranjería y Migración; Colombia: Migración Colombia, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores; Ecuador: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y de Movilidad Humana; Paraguay: Dirección General de Migraciones; Perú: Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones; Uruguay: Dirección Nacional de Migración-Ministerio del Interior and Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores. Years 2017-2018 do not include information from Ecuador and Peru.

Policy responses to migration from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela

The situation in the Bolivarian Republic of a Venezuela gave rise to 4,810,443 refugees, migrants and asylum seekers searching for better prospects in many countries around the world. Large numbers stayed in the region, and a considerable portion arrived in countries with very small immigrant populations, such as Colombia and Perú.

Massive inflows of people were entering into countries that were unprepared, generating critical situations, as was the case of border areas in Brazil and Colombia, and the borders between Colombia and Peru or Ecuador.

The Quito Declaration on Human Mobility of Venezuelan Citizens in the Region was followed by several technical meetings in which governments (including the Venezuelan government) specified concrete actions to provide humanitarian assistance; access to mechanisms of regular permanence; combat human trafficking and smuggling; prevent sexual and gender violence; provide child protection; reject discrimination and xenophobia; provide access to procedures for determining refugee status; and, in general, continue working on the implementation of public policies aimed at protecting the human rights of all migrants in their respective countries, in accordance with national laws and applicable international and regional instruments. Many of these initiatives have received technical assistance and support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and hundreds of NGOs.

Many good examples can be cited, from shelter and humanitarian transportation, food security and nutrition, to health and hygiene. Dozens of initiatives such as the granting of the Border Mobility Card (Colombia-the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela), simplifying educational title validation or prior obligatory education (Argentina), and speeding up processes of refugee recognition (Brazil) are just a few examples.

A crucial aspect of the integration process relates to the status of Venezuelans in receiving countries. South American countries have used and developed different mechanisms to incorporate them under regular terms. Permits with different requirements, entitlements and durations were granted, such as Special Permanent Permits, Visas and Alien ID cards in Colombia, Humanitarian visas and Temporary Permits of Residency in Peru, Democratic Responsibility and Tourist Visas in Chile.

It has been argued that from a juridical point of view, some of these permits are problematic mainly due to the lack of legal certainty for individuals and the discretionary way to handle them by executive powers.

It’s time to strengthen regional agreements and regional cooperation

Regional agreements have proven to be suitable instruments for improving mobility and migration and to protect the rights. Yet there is considerable room for improvements both at a regional and country level. At country level, immigrant integration is a matter that crosses several executive areas and should be treated integrally. Inter-institutional agencies (education, health, migration, labour, and so on) with participation of civil society organizations are good alternatives to design, execute and monitor public policy toward immigrants, and should thus be replicated in all immigrant-receiving countries.

A second important point is that since States are accountable for their commitments toward immigrants, monitoring national and regional obligations to immigrants requires the production of coordinated, timely and accurate information. These harmonized data collection systems should be sensitive to sex, age, ethnic and racial differences. Some advances had been made regarding the production of border statistics and administrative registration, yet these good practices should be extended to most sources collected in national statistical systems.

A main challenge is, therefore, how to strengthen dialogue through well-established organizations such as MERCOSUR, the Andean Community and the South American Migration Conference, among others. Certainly, it is through these organizations that coordinated steps to better provide articulated responses to crucial needs, including measures to prevent xenophobia and to favor social integration, can be ensured.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or the United Nations. Any designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the blog do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers and boundaries.