Lifting intraregional border controls

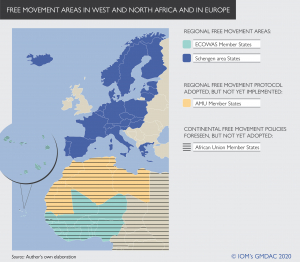

Most States in West and North Africa and in Europe are part of free movement areas. In the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Establishment” was introduced in 1979. Free movement policies were also mainstreamed in further policies of the community, such as the ECOWAS Common Approach to migration, adopted in 2008. In the European Union (EU), free movement of persons was already enshrined in the Treaty of Rome in 1957, and was then further consolidated by the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992. In both West Africa and Europe, free movement policies have facilitated intraregional mobility, which is much more prevalent than mobility between regions, and testified to a political recognition that this mobility is essential for regional economic integration and development. In the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), where in 2017 more than 90% of emigrants lived outside the continent (compared to 30% of West African migrants), free movement policies were foreseen in the 1989 Treaty establishing the Union, but have not yet adopted. An ambition to extend free movement policies exists also at the continental level: it has been present in the work of the African Union (AU) since its beginnings, and has recently gained momentum with the Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment, adopted in 2018.

The maintained importance of borders

However, borders have not lost in importance. In fact, divergent interests at the national level have in some cases hindered advancement on regional free movement policies or agreement on migration governance within free movement areas. These national differences have been due for example to political and socioeconomic differences between member states and to differences in migration-related interests, reflecting aspects as diverse as varying migration and remittances flows, labour market needs, demographic trends and geographical locations. In some cases, political difficulties, and institutional and administrative barriers have also been relevant. This has been the case in North Africa, where, as mentioned, advancement on free movement policies has been slow. In West Africa, as well, they have challenged the full implementation of the 1979 ECOWAS Protocol. In the EU, finally, they have rendered it difficult to identify a shared migration management system and led its member states to increase efforts on immigration control at the Union´s external borders.

The effects on interregional migration policy negotiations

These simultaneous trends towards lifting intraregional border controls and tightening external border controls have led to interregional dependencies in migration policy negotiations. In particular, migration governance in West and North Africa has been increasingly influenced by migration policy negotiations in the EU. This has taken place both directly, through transregional policy negotiations, and indirectly, as what is negotiated within one region contributes to shift the focus of interregional negotiations. For example, in recent years an increasing focus on external borders has led EU member states to increase efforts to engage on immigration control with West and North African states. However, related transregional negotiations have not been easy either, due to factors as diverse as the increasing policy relevance of migrants as actors of development in countries of origin, different public attitudes towards migration, national competencies on migration, development and security, or aspects such as regular migration pathways and return and readmission.

Conclusion

In the last decades a trend towards lifting intraregional border controls has unfolded in parallel with a maintained importance of national borders and in some cases with a trend towards tightening external border controls. This has influenced the negotiation of regional and transregional migration governance in West and North Africa and Europe. On the one hand, free movement policies were adopted quite early on in the ECOWAS and in the EU, and have been discussed for a long time in the AMU and the African Union. Their importance has also been reaffirmed through recent policy developments. On the other hand, their implementation remains challenging, as States have different interests with regard to migration, and may be hesitant to engage in regional migration governance structures. In the EU, they have been accompanied by a trend towards tightening external border controls and an increasing migration policy engagement West and North African states. Social and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic may have an impact on these aspects, as well, as they may reshape national migration-related interests.