Countries accepting dual citizenship from GLOBALCIT database.

Back to top

Definition

The following definitions have been adapted from the GLOBALCIT Glossary on Citizenship and Electoral Rights.

Citizenship - A legal status and relation between an individual and a state that entails specific legal rights and duties.

Citizenship is generally used as a synonym for nationality.

Where citizenship is used in a meaning that is different from nationality it refers to the legal rights and duties of individuals attached to nationality under domestic law. In some national laws, citizenship has a more specific meaning and refers to rights and duties that can only be exercised after the age of majority (such as voting rights) or to rights and duties that can only be exercised within the national territory.

Dual citizenship - Legal status of citizenship held by a person simultaneously in two (dual citizenship) or more states (multiple citizenship). Multiple citizenship may be acquired at birth or after birth and with or without the knowledge and consent of all the states involved.

The term refers only to the legal status and does not specify the rights and obligations a person holds vis-à-vis the state of second or third nationality where the person does not currently reside.

Ius sanguinis - The determination of a person’s citizenship on the basis of the citizenship of their parent(s) at the time of the person’s birth or at a later time.

Used in a broad way, ius sanguinis covers not only automatic acquisition at birth, but also non-automatic acquisition at birth and after birth.

Ius soli - The determination of a person’s citizenship on the basis of their country of birth.

Used in a broad way, ius soli covers not only automatic acquisition at birth but also non-automatic acquisition at birth and after birth.

Voting rights - Refers to "active voting rights", i.e., the right to cast a vote in an election.

Candidacy rights - Refers to “passive voting rights”, i.e. the right to stand as a candidate in an election.

Global patterns of birthright citizenship

All states award citizenship through the basic rules of ius soli and ius sanguinis. Most states mix elements of both rules. All 37 states (out of 190) where ius soli predominates, mostly in the Americas, provide at least the first generation born abroad to emigrant citizens with birthright citizenship by descent. Among the states where ius sanguinis predominates, an increasing number provide access to citizenship to the second or third generations born to immigrants or their descendants, conditional on parental residence (16 states) or parental birth in the territory (26 states). Forty-nine per cent of states globally include a special ius soli provision for children born on their territory who would otherwise be stateless. These are 90 per cent of states in Europe, 55 per cent in Asia and only 35 per cent in Africa. Since ius sanguinis dominates in these three continents, the absence of ius soli contributes to statelessness there (Van der Baaren and Vink, 2021).

Dual citizenship toleration – a global trend

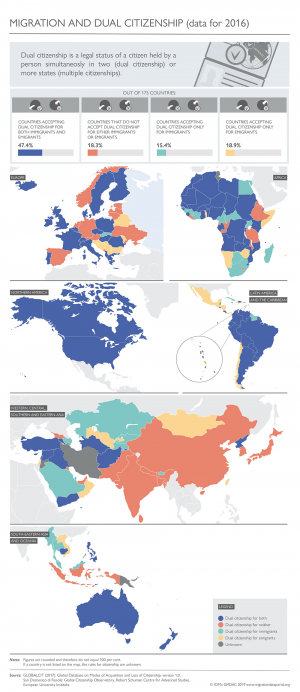

Until the 1960s, dual citizenship was viewed as problematic in international law and by most states, but now ever more countries accept dual citizenship as an unavoidable consequence of gender equality (mothers as well as fathers can transmit their citizenship to the child by descent) and transnational migration (migrants and their children acquire the citizenship of the destination country while retaining the citizenship of the origin country). As a result, in ever fewer countries citizenship is lost if another citizenship is acquired and in ever more destination countries migrants are no longer required to renounce their previous citizenship as a condition for naturalisation.

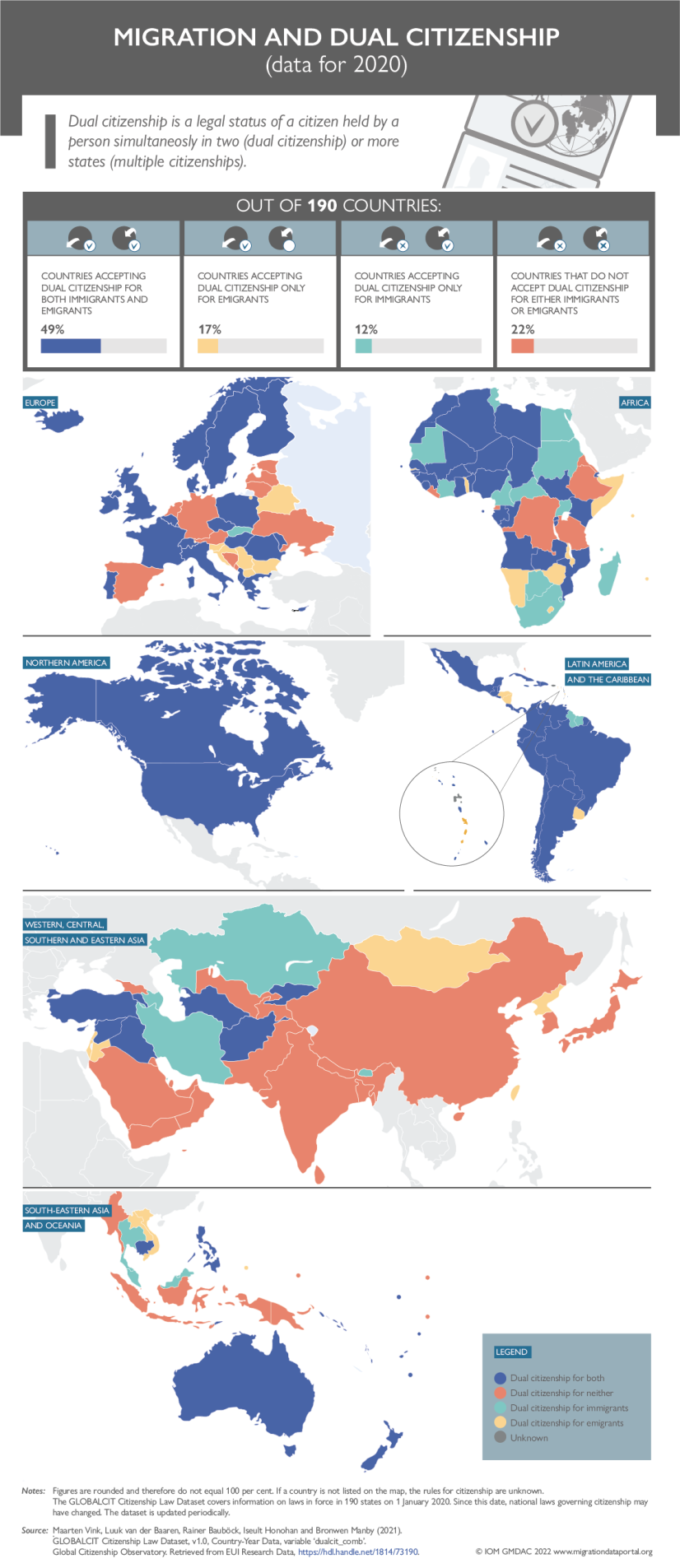

By 2020, 76 per cent of 200 countries examined tolerate dual citizenship for emigrants, allowing their citizens to voluntarily acquire the citizenship of another country without automatically losing their citizenship of origin. Dual citizenship acceptance for emigrants has progressed faster in the Americas, Europe and Oceania and more slowly in Africa and Asia (Vink et al, 2019). 61 per cent do not require immigrants to renounce their previous citizenship as a condition for naturalisation and 49 per cent tolerate dual citizenship for both their diasporas and immigrants. Among the 22 per cent that reject dual citizenship for either group, many states still accept dual citizenship if it is acquired at birth rather than through naturalisation (Van der Baaren and Vink, 2021).

Migrant voting rights in national, subnational and supranational elections

Voting rights in the Americas, the EU-27 states, the United Kingdom, Oceania and Switzerland have become more universal over the past two centuries as restrictions based on criteria such as race, sex or property have been lifted. Yet migrants are often still excluded either on grounds of citizenship or residence. There is a strong global trend of granting citizens residing abroad voting rights in national elections, but immigrants who have not acquired citizenship can only rarely vote in national elections. Chile, Ecuador, Malawi, New Zealand, and Uruguay are the only countries where national voting rights are granted to residents independently of their citizenship. In a few other countries, citizens of particular other states can vote in national elections on the basis of historical ties. However, in Europe and the Americas non-citizen residents often have the right to vote in supranational and subnational elections held in their country of residence. In the European Union, citizens of other Member States can vote in local elections. Moreover, 11 EU states, the United Kingdom, Norway, Iceland, 8 Swiss cantons and 8 South American countries grant all local residents voting rights independently of their citizenship (Schmid, Piccoli and Arrighi, 2019).

The following data sources have been compiled by GLOBALCIT at the European University Institute (EUI) in Fiesole, Italy, on the basis of customised questionnaires completed by country experts and verified by regional coordinators. The GLOBALCIT databases, providing comprehensive information on citizenship and electoral rights to policy makers, researchers, and the general public, are available in open access.

GLOBALCIT provides the most comprehensive source of information on the acquisition and loss of citizenship globally for policy makers, NGOs and academic researchers. Its website hosts a number of databases on domestic and international legal norms, citizenship and electoral rights indicators.

GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset

GLOBALCIT’s dataset on modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship provides standardised descriptions of citizenship laws that allow for international comparison. The dataset breaks down citizenship laws into 28 modes of acquiring citizenship by birth or naturalisation and 15 modes of losing citizenship by renunciation or withdrawal. The GLOBALCIT Citizenship Law Dataset, v1.0 covers information on legislation in force in 190 states on 1 January 2020. The Dataset will be updated periodically and gradually back-coded in time to cover the legal situation in previous years.

A detailed codebook outlines the comparative methodology, categorical coding scheme and the sources of the Dataset, as well as exportable data files.

GLOBALCIT CITLAW Global Birthright Indicators

GLOBALCIT’s Citizenship law indicators (CITLAW) assign scores and weights to specific legal provisions in countries’ citizenship laws to measure the purposes of citizenship law provisions. The Global Birthright Indicators dataset offers indicators calculated for 177 countries, based on citizenship legislation in force on 1 January 2016. They include all indicators for ius sanguinis and for ius soli at birth, but exclude ius soli after birth, i.e. acquisition of citizenship based on birth in the territory at the age of majority or after a period of residence. Scores between 0 and 1 represent degrees of restrictiveness or conditionality for acquiring citizenship by birth. This explanatory note provides further details.

Voting and candidacy rights data

An online GLOBALCIT database on Conditions for Electoral Rights allows users to search for comparable information based on legislation in force on 1 January 2019. Based on the qualitative database on electoral rights, the ELECLAW indicators measure the degree of inclusion of voting rights (VOTLAW) and candidacy rights (CANLAW) for three different categories of potential voters: resident citizens, non-resident citizens, and non-citizen residents. The most recent version includes the EU-28 and Switzerland, based on the applicable electoral laws in 2013 and 2015, and the Americas and Oceania, based on the applicable electoral laws in 2015.

Longitudinal dual citizenship data

MACIMIDE Global Expatriate Dual Citizenship Dataset, Harvard Dataverse, V5 – this dataset charts the rules in 200 countries from 1960 (or since independence) to 2020 with regard to the loss or renunciation of citizenship when a citizen of a state voluntarily acquires the citizenship of another state. The Extended Codebook refers to the relevant citizenship legislation.

Data compiled by GLOBALCIT are based on primary research done by country experts examining national citizenship and electoral legislation. They cover the content of the legislative provisions for the acquisition of citizenship and electoral rights in a comprehensive and detailed way. The datasets on modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship and on voting and candidacy rights allow users to go several steps beyond the indicators by linking directly to country reports, concise explanations and full text of the relevant legal provisions (both in the original language and an English translation).

At present, the GLOBALCIT data on citizenship laws are not longitudinal and are only available for 2020. The MACIMIDE dual citizenship dataset presents categorical data and has global coverage from 1960 to 2020, allowing for global comparison and analysis of patterns and trends. This dataset only covers dual citizenship acceptance for those acquiring the citizenship of another state, not for 'incoming' naturalisations by immigrants. An updated and expanded version of this dataset is expected to be launched by GLOBALCIT in 2022, covering both immigrant and emigrant dual citizenship acceptance. Present datasets on voting and candidacy rights cover the 28 EU member states for 2013 and the EU-28, Switzerland, the Americas, and Oceania for 2015, and are therefore not global in scope. GLOBALCIT is currently preparing a new global and longitudinal dataset on electoral rights for non-citizen residents and non-resident citizens.

Further reading

Van der Baaren, L. and Vink, M.

2021 "Modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship around the world: Comparative typology and main patterns in 2020". GLOBALCIT Working Paper, EUI RSC, 2021/90.

Vink, M., A.H. Schakel, D.Reichel, N. C. Luk, G-R de Groot

2019 "The international diffusion of expatriate dual citizenship". Migration Studies 7, no. 3: 362-383.

Shachar, A., Bauböck, R., Bloemraad, I. and Vink, M., eds.

2017 The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship. Oxford University Press.

Honohan, I. and Rougier, N.

2018 "Global Birthright Citizenship Laws: How Inclusive?" Netherlands International Law Review 65, no. 3 : 337-357.

Schmid, S. D., Piccoli, L. and Arrighi, J.

2019 "Non-universal suffrage: measuring electoral inclusion in contemporary democracies." European Political Science: 1-19.

Arrighi, J. and Bauböck, R.

2017 "A multilevel puzzle: Migrants’ voting rights in national and local elections." European Journal of Political Research 56, no. 3: 619-639.

This page was authored as a thematic contribution to the Global Migration Data Portal by GLOBALCIT, coordinated at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, with input from Rainer Bauböck, Jelena Dzankic, Lorenzo Piccoli, Luuk van der Baaren and Maarten Vink.

Back to top