Derechos de los migrantes

Según el derecho internacional, los migrantes tienen derechos humanos en virtud de su humanidad. El derecho consuetudinario internacional y los instrumentos internacionales de derechos humanos son de aplicación universal y, por tanto, establecen los deberes y derechos de los migrantes. Existen otros instrumentos internacionales que abordan específicamente la protección de los migrantes y sus derechos. Además, recientemente se ha llamado la atención sobre las obligaciones de los Estados, en virtud del derecho internacional de los derechos humanos, hacia los migrantes muertos y desaparecidos y sus familias (Grant, 2016).

El acceso de los migrantes a los derechos puede evaluarse midiendo los derechos concedidos a los migrantes en principio y en la práctica. Lo primero es relativamente sencillo y examina las ratificaciones de tratados internacionales y regionales por parte de los Estados y su legislación nacional para respetar, proteger y cumplir los derechos de los migrantes, mientras que lo segundo requiere examinar la aplicación de los derechos, o si los derechos de los migrantes se respetan y ejercen realmente. La medición de los derechos concedidos a los migrantes y su acceso efectivo en la práctica se ve limitada por la falta de datos, información y recursos, así como por el gran número de derechos que requieren evaluación.

Definiciones

Los derechos de los migrantes son los derechos de los migrantes establecidos implícita o explícita por la legislación internacional sobre migración, incluidos los derechos humanos internacionales (véase la lista 1 infra) y otros instrumentos de derecho público (véase la lista 2 infra). Medir los derechos de los migrantes exclusivamente a través de un enfoque basado en los derechos humanos — un enfoque que sólo tiene en cuenta los instrumentos internacionales de derechos humanos- no abarca toda la gama de derechos de los migrantes establecidos por otros instrumentos. Por otra parte, un enfoque basado en los derechos reconoce que los derechos de los migrantes están concedidos no sólo por la normativa de derechos humanos, sino también por los tratados de otras ramas del derecho internacional público, entre los que se incluyen:

- El derecho de los refugiados;

- El derecho penal transnacional, especialmente los tratados relativos a la trata y el tráfico ilícito de personas;

- El derecho humanitario;

- El derecho laboral y

- El derecho del mar.

Aunque los derechos de los migrantes se derivan del derecho consuetudinario internacional (es decir, el derecho resultante de una práctica general y coherente de los Estados que siguen por un sentido de obligación jurídica), esta página temática se centra en el derecho de los tratados.

Tendencias recientes

Los derechos de los migrantes han surgido como parte del marco jurídico internacional de los derechos humanos, codificado después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en la Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos y en los posteriores tratados de derechos humanos adoptados por los Estados. De hecho, los derechos humanos no son sólo los derechos de los nacionales, sino los derechos que pertenecen a todos los individuos que están bajo la jurisdicción de un Estado (es decir, todos los individuos que se encuentran en el territorio de los Estados o bajo el control efectivo de los agentes del Estado). El principio de no devolución (que protege de la devolución a todas las personas que corren un riesgo real de sufrir daños irreparables para su vida, su integridad física u otras violaciones graves de los derechos humanos si son devueltas a su país de origen), se ha codificado en la Convención sobre el Estatuto de los Refugiados y su Protocolo, así como en la Convención contra la Tortura. Desde entonces se considera que forma parte del derecho consuetudinario internacional y es absoluto. Esto significa que este principio de no devolución se aplica en todo momento cuando se cumplen sus criterios de aplicación, y nunca puede suspenderse o limitarse, ni siquiera en tiempos de crisis o estado de emergencia. Aunque es difícil identificar "tendencias" en los derechos concedidos específicamente a los migrantes en distintos instrumentos internacionales, las listas anteriores ponen de manifiesto el calendario de ratificaciones de los tratados internacionales relativos a los derechos de los migrantes. La mayoría de los tratados fueron ratificados antes del año 2000. El tratado más reciente, el Convenio sobre el Trabajo Decente para los Trabajadores Domésticos, que es de suma importancia para muchos trabajadores migrantes, fue adoptado en 2011.

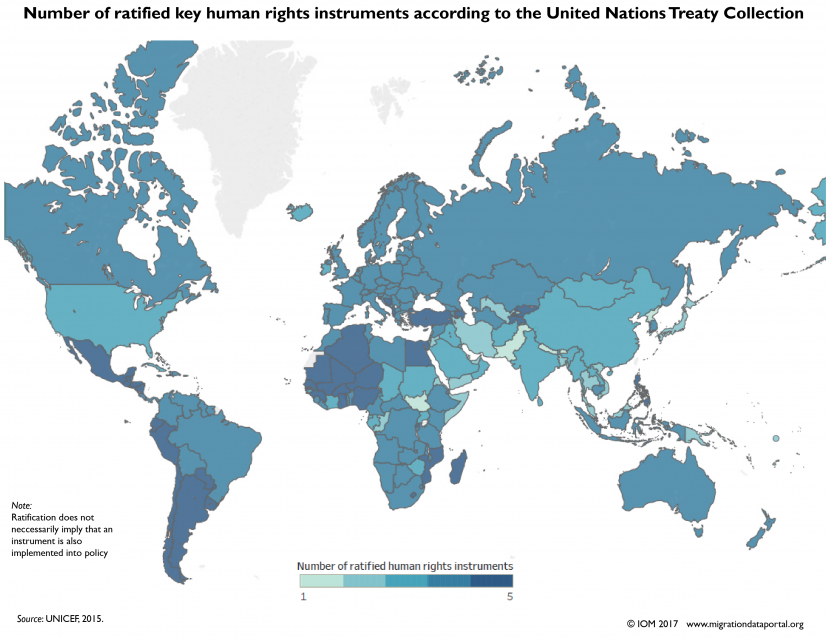

Varios de los tratados mencionados han registrado un número importante de ratificaciones en los últimos años y muchos de ellos han sido ratificados ampliamente por los Estados. En particular, dado que los derechos humanos fundamentales son también derechos de los migrantes, todos los Estados han ratificado al menos uno de los tratados de derechos humanos fundamentales y el 80% ha ratificado cuatro o más.

Para conocer el estado de ratificación de los Tratados de Derechos Humanos, visite aqui. Para comprobar la situación actualizada de la ratificación de los tratados internacionales, visite aqui

Aunque actualmente es difícil medir los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica, la inclusión de temas relacionados con la migración en los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS) y la adopción del Pacto Mundial para la Migración Segura, Ordenada y Regular en 2018 pueden conducir a mejores medios de medir el cumplimiento estatal de las obligaciones legales internacionales en el contexto de la migración. Además, los Indicadores de Gobernanza de la Migración (MGI), una herramienta de política que evalúa la gobernanza de la migración a nivel nacional y local, incluye los derechos de los migrantes como uno de los seis dominios de gobernanza de la migración que mide. El MGI, por ejemplo, analiza hasta qué punto los migrantes en los países y en las ciudades tienen el mismo estatus que los ciudadanos en términos de acceso a servicios sociales básicos como salud, educación y seguridad social. Ver más

Fuentes de datos

Se han publicado varias normas y directrices para producir datos sobre los derechos de los migrantes, entre las que se encuentran:

-

Las Recomendaciones sobre Estadísticas de las Migraciones Internacionales de las Naciones Unidas (1998).

-

Los Principios y recomendaciones para los censos de población y habitación de las Naciones Unidas (2008).

-

Las observaciones y recomendaciones generales aprobadas por los órganos de tratados que guardan relación con los derechos de los migrantes.

También hay diversas fuentes de datos que miden los derechos de los migrantes en principio. Estas evalúan la ratificación de los tratados, los acuerdos bilaterales y multilaterales y la legislación nacional, y se enumeran a continuación.

Fuentes de datos que miden los derechos de los migrantes en principio o la ratificación de tratados

| Nivel | Fuente de información |

|---|---|

| Mundo | Oficina del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos (ACNUDH) Colección de Tratados de las Naciones Unidas Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT) |

| Europa | Consejo de Europa |

| África | Unión Africana |

| Las Americas | Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA) |

| Asia Sudoriental | Asociación de Naciones de Asia Sudoriental (ASEAN) |

A los efectos de este portal, los derechos que se otorgan a los migrantes en principio se miden por medio de los datos relativos a la ratificación de tratados.

Además, hay diversas fuentes de datos que miden los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica. A diferencia de las que miden los derechos de los migrantes en principio —que no tienen en cuenta la aplicación real de la legislación internacional, regional y nacional—, las fuentes de datos que miden los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica ofrecen marcos que establecen indicadores cualitativos y cuantitativos de los derechos a fin de evaluar la observancia de los derechos de los migrantes. Existen varios marcos de ese tipo, a saber:

-

El Índice Universal de Derechos Humanos (UHRI): El UHRI le permite explorar más de 170.000 observaciones y recomendaciones realizadas por el sistema internacional de protección de los derechos humanos (es decir, los Órganos de Tratados, el Examen Periódico Universal y los Procedimientos Especiales) https://uhri.ohchr.org/en/

-

El Foro Internacional de Revisión de la Migración: En el Pacto Mundial para una Migración Segura, Ordenada y Regular, los Estados miembros decidieron que el Foro Internacional de Revisión de la Migración servirá como la principal plataforma global intergubernamental para discutir y compartir los avances en la implementación de todos los aspectos del Pacto Mundial. El Foro Internacional de Revisión de la Migración se celebrará cada cuatro años a partir de 2022, y las revisiones regionales intermedias tendrán lugar en el período previo al FIM. https://migrationnetwork.un.org/international-migration-review-forum-2022

-

La Alianza Mundial de Conocimientos sobre Migración y Desarrollo (KNOMAD) proporciona un marco de indicadores sobre los derechos de los migrantes, en particular, los derechos a la no discriminación, la educación, la salud y el trabajo decente (Hernandez, 2017). El marco se basa en el modelo de indicadores creado por el ACNUDH (véase infra). Hay estudios de casos relativos a la Argentina, Túnez y México.

-

Aunque no se centran únicamente en los derechos de los inmigrantes, los perfiles del IGM incluyen una evaluación de cómo los países y las ciudades gobiernan cuestiones como el acceso de los inmigrantes a los servicios sociales básicos y a la seguridad social, la reunificación familiar, el derecho al trabajo, la residencia de larga duración y el camino hacia la ciudadanía, y la participación civil. Ver más

-

El marco del ACNUDH establece indicadores generales de derechos humanos que sirven de modelo para muchos otros marcos de indicadores de derechos, si bien no aborda específicamente los derechos de los migrantes.

-

La OEA ofrece un marco de indicadores de los derechos económicos, sociales y culturales en América.

-

La OIT ha elaborado indicadores de los marcos estadísticos y jurídicos en relación con el trabajo decente que pueden resultar útiles para evaluar los derechos de los trabajadores migrantes.

Si bien estos marcos establecen indicadores que se pueden utilizar para medir los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica, por lo general no determinan qué tipos de datos se pueden utilizar. Para medir los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica, pueden utilizarse los cuatro tipos de datos siguientes:

| Tipo de datos | Descripción | Ejemplos |

| Datos sobre casos concretos | Hacen un seguimiento de vulneraciones específicas de los derechos de los migrantes por parte de agentes estatales y no estatales. Para contabilizar esos eventos y vulneraciones, es necesario determinar los diversos actos u omisiones que constituyen o dan lugar a violaciones de los derechos humanos. Ejemplos de este tipo de datos son los comunicados de prensa y las noticias publicados por los medios de comunicación, los Gobiernos y las ONG. | Comunicados de prensa del ACNUDH relativos a los derechos de los migrantes y los refugiados |

| Datos basados en opiniones de expertos | Los datos se basan en las valoraciones de una situación de los derechos humanos realizadas con la ayuda de un número limitado de expertos con conocimiento de causa, que evalúan y califican la actuación de los Estados. Por lo general, se trata de informes elaborados por grupos de defensa de los derechos o por investigadores universitarios. |

Informes de Human Rights Watch sobre refugiados y migrantes Informes de los Estados partes al Comité sobre los Trabajadores Migratorios. Informes de los Estados parte, lista de cuestiones y observaciones finales a los respectivos órganos de tratados de derechos humanos Informes sobre la trata de personas del Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos |

| Datos de encuestas | Para generar estos datos, se utilizan muestras de población de los países a las que se plantean preguntas tipificadas sobre las percepciones o las experiencias en lo que se refiere a las medidas de protección de los derechos de los migrantes. Pueden utilizarse para crear indicadores socioeconómicos o basados en la opinión. |

Encuestas resumidas del Centro de África Septentrional para la Migración Mixta. Iniciativa del Mecanismo de Seguimiento de la Migración Mixta de la Secretaría Regional de Migración Mixta |

| Estadísticas oficiales | Datos recopilados por los organismos oficiales a nivel nacional y subnacional mediante definiciones y metodologías normalizadas. Si bien el objetivo de esos datos no es explícitamente medir los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica, en ocasiones incluyen información a este respecto. Algunos ejemplos de este tipo de datos son los datos administrativos, las encuestas estadísticas realizadas con determinados segmentos de población o los datos obtenidos mediante censos. | Datos sobre las muertes acaecidas en la frontera sudoccidental, recopilados por la Patrulla Fronteriza de los Estados Unidos |

Puntos fuertes y limitaciones de los datos

Las fuentes de datos que miden los derechos de los migrantes en principio permiten evaluar la defensa de los derechos de los migrantes por parte de los Estados y comparar su nivel de compromiso con la protección de esos derechos. Sin embargo, estas fuentes no miden la aplicación real por parte de un Estado del respeto, la protección y el cumplimiento de los derechos de los migrantes.

Las fuentes de datos que miden los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica hacen una valoración más precisa del grado en que un país cumple sus obligaciones internacionales en lo referente a los derechos de los migrantes, pero es mucho menos probable que sean comparables entre países, y, en ocasiones, los datos resumidos carecen de información contextual importante sobre la situación de los migrantes en un determinado Estado. También se ha de tener en cuenta que la producción de datos estadísticos que conlleva la recopilación y publicación de datos sobre los migrantes, especialmente los migrantes irregulares, tiene implicaciones relacionadas con la privacidad, la protección de datos y la confidencialidad.

Los cuatro tipos de datos señalados anteriormente que permiten la medición de los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica también presentan sus propios puntos fuertes y limitaciones. Estos puntos fuertes y limitaciones, que se enumeran a continuación, no afectan solamente a la medición de los derechos de los migrantes, sino que se trata de cuestiones relacionadas con el tipo de fuente de datos.

Puntos fuertes y limitaciones de los datos para medir los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica

| Tipo de fuente de datos | Puntos fuertes | Limitaciones |

|---|---|---|

| Datos sobre casos concretos |

Vinculados explícitamente con incidentes concretos que ponen de manifiesto el cumplimiento o incumplimiento de las normas de derechos humanos. Suelen incluir información contextual que resulta importante para entender la situación de los migrantes en un país determinado. |

Es posible que no ofrezcan una visión completa de los derechos que tienen los migrantes en el lugar en el que tuvo lugar el incidente. Por lo general, los datos no son comparables entre Estados. En ocasiones, la exactitud y la calidad de los datos dependen de quién elaboró el informe. |

| Datos basados en opiniones de expertos | Pueden recopilarse con rapidez, por lo que son útiles para presentar un análisis preliminar de una situación. | Como ocurre con los datos sobre casos concretos, los datos basados en opiniones de expertos suelen ser poco fiables y, por lo general, no son comparables entre países. |

| Datos de encuestas |

Hacen un seguimiento de las experiencias individuales en relación con vulneraciones de los derechos. Suelen incluir información contextual que resulta importante para entender los derechos de los migrantes.

|

Como ocurre con otros tipos de datos subjetivos, es posible que los datos de encuestas no siempre den una indicación fiable de los derechos de los migrantes. Si no se conoce la composición de una comunidad de migrantes, las limitaciones de las muestras no serán representativas de la población en general.

|

| Estadísticas oficiales | Pueden ser una manera fiable y económica de medir los derechos de los migrantes en la práctica. |

En Estados o regiones con menos recursos, es posible que esos datos no sean precisos ni fiables. Muchos países no desglosan los datos por situación migratoria o de residencia. Aun cuando se dispone de datos desglosados, las diferencias en las definiciones de lo que constituye un migrante dificultan la comparación entre países. |

Lecturas adicionales

| Hernandez, C. | |

|---|---|

| 2017 | Chapter 14: Human Rights of Migrants. In: Handbook for Improving the Production and Use of Migration Data for Development. Global Knowledge Partnership for Migration and Development (KNOWMAD), World Bank, Washington, D.C. |

| International Organization of Migration (IOM) | |

| 2015 | Rights-based approach to programming. IOM, Geneva. |

| Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) | |

| 2012 | Human Rights Indicators: A Guide to Measurement and Implementation. OHCHR, Geneva. |

| Ceriani Cernadas, P., M. LeVoy and L. Keith | |

| 2015 | Human Rights Indicators for Migrants and their Families. KNOMAD Working Paper 5, KNOMAD, Washington D.C. |

| KNOMAD | |

| 2015 | Human Rights Indicators for Migrants and their Families: Overview. KNOMAD, Washington, D.C. |

| United Nations Development Programme, UNDP | |

| 2006 | Indicators for Human Rights-based Approaches to Development in UNDP Programming: A Users Guide. UNDP, New York. |

| Córdova Alcaraz, R. | |

| 2017 | Human Rights Indicators for Migrants in Mexico: National Consultation Report. KNOMAD Working Paper 23, KNOMAD, Washington D.C. |

| Hanafi, S. | |

| 2017 | Indicators for Human Rights of Migrants and their Families in Tunisia. KNOMAD Working Paper 24, KNOMAD, Washington D.C. |

| International Labour Office | |

| 2010 | Manual on Decent Work Indicators. Guidelines for Producers and Users of Statistical and Legal Framework Indicators. International Labour Organization, Geneva. |

| International Labour Office | |

| 2010 | International Labour Migration: A Rights-based Approach. International Labour Organization, Geneva. |

| Organization of American States (OAS) | |

| 2015 | Progress Indicators for Measuring Rights under the Protocol of San Salvador. OAS, Washington D.C. |

- 1La Declaración Universal no es un tratado, por lo que no necesita ser ratificada ni crea directamente obligaciones legales para todos los miembros de la comunidad internacional. Sin embargo, es una expresión de los valores fundamentales que comparten todos los miembros. Además, ha tenido una profunda influencia en el desarrollo del derecho internacional de los derechos humanos y ahora se considera derecho consuetudinario internacional.