Environmental Migration

Quantifying environmental migration, displacement and mobility is challenging given the multiple drivers of such movement, related methodological challenges and the lack of data collection standards. Some quantitative data exist on population displacement within a country, and to a lesser degree across borders, due to natural hazards. However, for mobility due to slow-onset environmental processes, such as drought or sea-level rise, most existing data are qualitative and based on case studies, with few comparative studies. While research methodologies are constantly being improved, and projection models for future mobility due to climate are being developed, data gaps still persist.

Definitions

Some key terms are important in the context of migration and environmental and climatic changes:

- Human mobility is “a generic term covering all the different forms of movements of persons.” In the context of environment drivers, human mobility is understood as encompassing the three forms of “climate change induced” movement from the Cancun Agreement namely, displacement, migration, and planned relocation (IOM, n.d.).

- Environmental migration is the “movement of persons or groups of persons [environmental migrants] who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are forced to leave their places of habitual residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move within or outside their country of origin or habitual residence. There is no international agreement on a term to be used to describe persons or groups of persons that move for environment related reasons. This definition of environmental migrant is not meant to create any new legal categories. It is a working definition aimed at describing all the various situations in which people move in the context of environmental factors" (IOM, 2021).

- Climate migration is the movement of a person or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment due to climate change, are obliged to leave their habitual place of residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within a State or across an international border. (IOM, 2019). Climate migration is a subcategory of environmental migration; it defines a singular type of environmental migration, where the change in the environment is due to climate change.

- Climate refugees or environmental refugees: There is a growing consensus among concerned agencies, including IOM and UNHCR, that the use of these terms is to be avoided. These terms are misleading and fail to recognize a number of key aspects that define population movements in the context of climate change and environmental degradation, including that environmental migration is mainly internal and not necessarily forced, and the use of such terms could potentially undermine the international legal regime for the protection of refugees (IOM, n.d.)

- Environmentally displaced person refers to “persons who are displaced within their country of habitual residence or who have crossed an international border and for whom environmental degradation, deterioration or destruction is a major cause of their displacement, although not necessarily the sole one” (IOM, 2011:34 in IOM, 2014:13).

- Disaster displacement “refers to situations, where people are forced or obliged to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of disasters triggered by natural hazards. Such displacement may take the form of spontaneous flight or an evacuation ordered or enforced by authorities. Such displacement can occur within a country, or across international borders” (The Nansen Protection Agenda, 2015).

- Planned relocation “in the context of disasters or environmental degradation, including when due to the effects of climate change, [refers to] a planned process in which persons or groups of persons move or are assisted to move away from their homes or place of temporary residence, are settled in a new location, and provided with the conditions for rebuilding their lives. The term is generally used to identify relocations that are carried out within national borders under the authority of the State and denotes a long process that lasts until “relocated persons are incorporated into all aspects of life in the new setting and no longer have needs or vulnerabilities stemming from the Planned Relocation. (IOM, 2019 ; Georgetown University, UNHCR, and IOM, 2017).

- Trapped populations refers to populations “who do not migrate, yet are situated in areas under threat, […] at risk of becoming ‘trapped’ or having to stay behind, where they will be more vulnerable to environmental shocks and impoverishment” (IOM, 2019).

Recent trends

Among the total of 46.9 million new internal displacements registered in 2023, 56 per cent were triggered by disasters (IDMC, 2024). In IDMC data collection, disaster-induced displacements include both weather-related hazards (e.g. storms, floods and wildfires) and geophysical hazards (e.g. earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis) (IDMC, n.d.). As of 31 December 2023, at least 7.7 million people in 82 countries and territories were living in internal displacement as a result of disasters that happened not only in 2023, but also in previous years (ibid.). This represents 11 per cent decrease in the total number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to disasters compared to 2022 (ibid.). Disaster displacement in 2023 was the third highest figure in the last decade, even though there were one third fewer displacements due to weather-related hazards, partly resulting from La Niña’s end and El Niño’s onset.

The top 5 countries with the highest number of new internal displacements due to disasters in 2023 were China (4.7 million), Türkiye (4.1 million), Philippines (2.6 million), Somalia (2 million), and Bangladesh (1.8 million) (ibid.).

Seventy-seven per cent of the 26.4 million new internal disaster displacements in 2023 were the result of weather-related hazards such as storms, floods and droughts (ibid.). Floods remained the hazard displacing most people, causing 9.8 million internal displacements, closely followed closely by storms, causing 9.5 million internal displacements (ibid.). Almost a quarter of all internal displacements were due to earthquakes, especially those in Türkiye, Syria, the Philippines, Afghanistan and Morocco. In 2023 earthquakes and volcanic activity caused the same number of displacements as the total of the previous seven years (ibid.). Some of these earthquakes struck areas where displaced persons from conflict were already living, e.g. in Syria and Afghanistan (ibid.).

The impact of the COVID-19pandemic continues to affect internally displaced persons around the world, particularly from the loss of livelihoods and food insecurity (IDMC 2021; IDMC 2022; IDMC 2023). In addition, climate change is changing precipitation and temperature patterns and increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events in many parts of the world, all of which affect food security by reducing agricultural production (IPCC, 2022), causing people to move seasonally or permanently from at-risk areas. Both disasters associated with sudden-onset hazards such as hurricanes and floods and slow-onset events such as droughts and sea-level rise contribute to food insecurity through the destruction of infrastructure and degradation of livelihoods, which in some cases leads to a decision to migrate (IOM, 2024). Read more about climate change, food security and human mobility here.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)projects that more than one billion people globally could be exposed to coastal-specific climate hazards by 2050, potentially driving tens to hundreds of millions of people to leave their home in coming decades (IOM, 2022; IPCC, 2022),

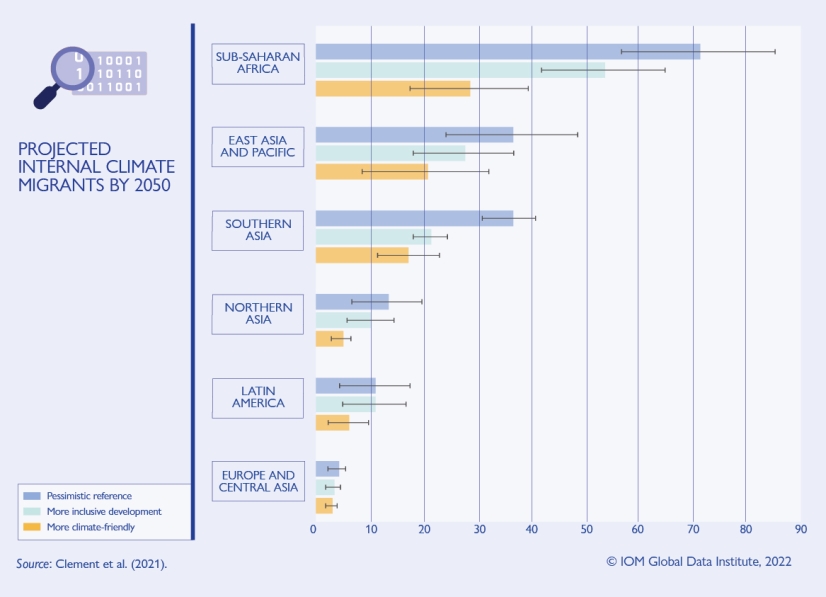

Slow-onset processes such as droughts or sea level rise also increasingly affect people’s mobility worldwide. In this regard, the World Bank’s Groundswell report projects that climate change could lead up to 216 million people across six world regions (Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Latin America, East Asia and the Pacific, North Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia) to move within their countries by 2050 if no urgent action to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions is taken (Clement et al. 2021).

“When I was a child, everything was different. There was plenty of grass, water, and animals. But now there is nothing except for drought,” explains Ekuwom. The 60-year-old former pastoralist has seen his livelihood slowly die out due to the recent droughts plaguing Turkana country, in Northern Kenya. For many pastoralists in Northern Kenya, migration was a necessary part of life as herds of animals would travel long distances to graze on fresh grass that would change according to the seasons. Many would often cross borders in search of food and water in regular cycles. Due to climate change, the land across the entire region has become increasingly arid, leaving little to no water and food for animals. Today, Ekuwom has been displaced from his home community and forced to live in Namon village, a community along a major migratory route. The scorching heat has even made farming difficult leading to some in search of alternative livelihoods such as charcoal burning. As an outsider to the community, Ekuwom feels the alienation from others “because I am not from here, I can feel the discrimination from others. Whenever aid is brought to this community from other organizations, displaced people like myself are always the last the receive any.” Photo: IOM 2023 / Muse Mohammed.

Data sources

Comprehensive datasets on environmental migration or planned relocation do not yet exist at the global level, but several initiatives have started to collect information across several countries. The following list provides an overview of the available information, including more qualitative research.

Primary data collection:

National authorities collect information on displacement and evacuations linked to disasters, both in collecting data at the national, sub-national and local level, and also in coordination with other actors such as international organizations. Examples of national displacement databases include Brazil’s Integrated Disaster Information System, the Philippines Disaster Response Operations Monitoring and Information Center (DROMIC) database, Uruguay’s MIRA database, and Sri Lanka’s Desinventar database; analyses of these can be found in IOM, 2024. While national data is crucial for national and sub-national information and response, methodologies and displacement definitions between national authorities are not standardized, so these databases have limited comparability on an international level. Local-level disaster displacement data are available from (international and national) humanitarian agencies (NGOs, UN agencies) engaged in relief operations, which collect data in order to respond to the needs of affected populations. Planned relocation of communities in the context of environmental and climate change is increasingly implemented by governments. For a summary of relocation programmes, see Ionesco, Mokhnacheva and Gemenne, 2016; Benton, 2017 and Georgetown University, UNHCR and IOM, 2017).

International and national humanitarian agencies (NGOs, UN agencies) engaged in relief operations collect data in order to respond to the needs of affected populations, providing local-level disaster displacement data. IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is a system used to track and monitor disaster displacement and population mobility. Data, which can be disaggregated by gender and sex, are regularly captured, processed and disseminated to provide a better understanding of the movements and evolving needs of displaced populations and migrants, whether in situ or en route, before, during and in the aftermath of disasters. The data are presented in the DTM Data Portal. A study on how current DTM practices collect data on human mobility in the context of environmental degradation, climate change and disasters also provides recommendations on how to improve current tools and practices. Recommendations include improving the focus of some DTM questions and increasing the amount of options available for respondents to provide more granular data on the mobility , environment and climate nexus (IOM, 2023).

Administrative data sources, such as the numbers of humanitarian visas (such as in the US, Brazil, Ecuador or Mexico) or residence permits granted (for instance, by Argentina) linked to disasters, can provide information on cross-border displacement and movements in the context of environmental events more generally.

Innovative data sources include mobile phone-based sources such as call detail records (CDRs). Big data generated by mobile phone users before and after disasters, such as the 2010 earthquake in Haiti (Bengtsson et al., 2011) and several typhoons in the Philippines and Bangladesh (Lu et al., 2016), can indicate where displaced persons moved to and help deliver prompt and targeted humanitarian assistance or to understand internal movements (Laczko and Rango, 2014; GMG, 2017). Meta’s Data for Good collects mobility data from its users and compiles datasets such as the Facebook Movement During Crises datasets for example around the volcanic explosion in St Vincent and the Grenadines in 2021. Mobile phone-based data can be a means to collect complementary quantitative data on movements at small-scale and on seasonal patterns linked to adaptation to environmental change and disasters that are difficult to account for in traditional household survey tools (Lu et al., 2016). Other projects aim at using big data sources, such as satellite images or social media data, to identify early the environmental stressors that could lead to displacement (see for instance Isaacman et al., 2017).

Several research projects have and are collecting new data on the links between the environment and human mobility, but few with a comparative approach. There are three notable exceptions. First, the Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Evidence for Policy (MECLEP) project, implemented by IOM and six research partners in 2014-2017, and funded by the EU, conducted a comparative quantitative and qualitative study of six countries (Dominican Republic, Haiti, Kenya, Papua New Guinea, Mauritius and Viet Nam). The methodology developed for the project could easily be applied to other countries.

Second, the Pacific Climate Change Migration and Human Security (PCCCMHS) programme by in partnership with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), International Labour Organization (ILO), Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS), Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) between 2019 and 2021 sought to protect and empower communities adversely affected by climate change and disasters in the Pacific region, focusing specifically on climate change and disaster-related migration, displacement, and planned relocation.

Third, the HABITABLE project is a EU-funded project (2020-2024) aiming at significantly advancing our understanding of the current interlinkages between climate impacts and migration and displacement patterns, and to better anticipate their future evolution. Led by the Hugo Observatory, the project brings together 21 partners from 18 countries and focuses on four regions: West Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa and South-East Asia.

Secondary data sources and research:

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) has compiled data on internal displacement in the context of disasters since 2008 globally through its online Global Internal Displacement Database (GIDD). The estimates are based on information by national authorities, UN agencies including IOM, the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), non-governmental organizations and in particular media reports. Figures are published in the annual Global Report on Displacement (GRID), which also covers internal displacement due to conflict and violence. IDMC is developing methodologies to map and assess future disaster displacement risks and is starting to gather data on cross-border displacement.

The HELIX project (High-End Climate Impacts and Extremes) provided research on climate impacts and adaptation in relation to varying global warming scenarios (2, 4 and 6 degrees Celsius), using predictive analytics. Human migration was included in the impact studies. The recent Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration report (Rigaud et al., 2018) developed a model for future population distribution in 2050 in three regions (sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America) if no action is taken.

The CLIMIG database of studies on environmental migration, both of qualitative and quantitative nature, was developed by the University of Neuchatel (Switzerland).

The Environmental Migration Portal by IOM, features a searchable research database, initially based on the People on the Move in a Changing Climate: A Bibliography, published by IOM in collaboration with University of Neuchatel. The database also includes migration and environment country assessments published by IOM.

The thematic working group on “Environmental change and migration” of the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) produced an annotated bibliography on Environmental Migration and developed a toolkit on planned relocation with many case study examples (Georgetown University, UNHCR and IOM, 2017).

The first “Atlas on Environmental Migration” was produced by IOM and Sciences Po, Paris (published with Routledge in 2017). The publication brings together, for the first time, existing knowledge on the links between migration and environmental change, presented through comprehensive maps, diagrams and case studies.

The Hugo Observatory at the University of Liège (Belgium) focuses on research on environmental changes and migration. IOM in collaboration with the Hugo Observatory and the City of Paris worked on the Climate Migration in Urban Areas project in 2022 to assist cities in their efforts to better understand how climate and environmental change will affect migration and urbanization trends and to include these considerations in urban planning and key sectoral policies.

The Platform on Disaster Displacement (a follow-up to the Nansen Initiative) provides a global dataset including preliminary findings from over 400 planned relocation cases. Last updated in 2021, it features characteristics including geographic location, spatial pattern, primary hazard and completion status.

IOM GDI’s interactive Climate Mobility Impacts dashboard visualizes where hazard exposure, high population density, and economic vulnerability are projected to coincide in future. These data help identify hotspots sensitive to heatwaves, river floods, drought, wildfire, tropical cyclone and crop failure, and users can map hazards regionally and under two climate warming scenarios and three socio-economic scenarios. These data can also develop effective anticipatory action to support at-risk communities worldwide.

The CLIMB database contains policy and legal instruments and practices addressing human mobility in the context of the adverse effects of climate change, disasters, and environmental degradation. The tool provides a resource for policymakers as well as researchers, practitioners and other stakeholders working in the area of policy development on human mobility, disasters, climate change, and environmental degradation.

Back to topData strengths & limitations

Over the past decade, important advances in methodologies and data collection have been made. Academic researchers and specialized agencies are working on improved methodologies for comparative cross-country or cross-region studies, agent-based models and multi-factor simulators designed to predict future trends (such as drought-induced displacement modelling, Ginnetti and Franck, 2014, or IDMC’s Global Displacement Risk Model focused on sudden-onset disasters based on housing destructions), and hotspot identification triangulating environmental and social data, all of which can contribute greatly to improving current evidence and future projections of environmental migration trends so as to better inform policies and action.

Innovative data sources: Big data can provide opportunities that can further be strengthened in trying to estimate the extent of movements in contexts of disasters and degrading environments. These new methods can fill gaps in time series data, indicate where people have moved from and to and enhance the timeliness of this information. In some cases, these new methods could be used to inform life-saving early warnings. At the same time, privacy safeguards and ethical considerations need to be adhered to.

Nonetheless, difficulties remain.

- It is challenging to differentiate when the environment is the main factor triggering migration, rather than or in combination with other factors: In most cases, environmental factors are closely linked to socioeconomic, political, demographic, cultural and personal factors that play a role in leading to or preventing mobility (Laczko and Aghazarm, 2009; Foresight, 2011), which makes data collection beyond fast onset disasters leading to evacuations difficult. Information on people moving due to more gradual, so-called slow-onset processes like sea level rise or salinization, is scarce for methodological reasons.

- The most comprehensive data available do not capture duration of displacement: Thanks to IDMC’s work, data on internal displacement due to disasters are available for almost all countries. However, differing definitions used by data providers and a lack of reporting by countries remains a challenge, leading to media reports being an important source of events covered in the estimates. IDMC’s estimates reflect new displacements during a calendar year (and since 2019, the stock of IDPs due to disasters as of the end of the year) and does not capture the duration of people’s displacement, their return home or relocation elsewhere, those not sheltered in camps or people caught in long-term displacement, so-called protracted situations, from year to year. Data collection on cross-border movements after disasters is only starting and limited to localized case studies (IDMC, 2018 (a)). Further research on disaster displacement is being supported as part of the work of the Data and Knowledge Working Group of the State-led Platform on Disaster Displacement.

- Underreporting: The quality and the availability of data on displacement vary between countries and from event to event: small-scale events or disasters that occur in isolated and marginalized areas are under-reported and thus not included in the available aggregate estimates (IDMC, 2017: 98; IDMC, 2018 (a)).

- Little information on links between conflict and disaster displacement: In cases where conflict is linked to disasters information on movements is lacking, in particular on displacement histories that could inform future predictions (IDMC data for instance are only available since 2008 but since 2017 include drought figures).

- Comprehensive datasets on environmental migration or planned relocation are needed: Data on environmental migration and planned relocation have improved in recent years, as an increasing number of studies have been conducted in affected areas. The research databases listed above are important tools providing an overview of the existing available information. However, comparable quantitative, longitudinal, disaggregated and georeferenced data are needed to assess how different forms of mobility can be a beneficial adaptation strategy and what potential risks need to be minimized. The majority of existing surveys focus mainly on the links between migration and the environment as a driver, and are mostly qualitative in nature. More information is needed on the impacts of those movements on adaptation to environmental and climate change.

- Few data on trapped populations: Some populations affected by environmental degradation and disasters may not be able to move due to a lack of financial resources, disability, social reasons (such as gender issues) or social networks. They are highly vulnerable populations, but data to inform action and protection are scarce.

- Better predictive analytics are needed: When it comes to predicting future trends, the disconnection between the environmental sciences and social sciences communities constitutes an additional challenge, in a context where environmental migration research would greatly benefit from multidisciplinary research and better integration of climate and population data.