Family migration

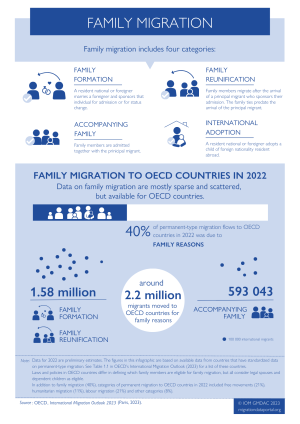

Family is a major driver of migration. Family migration is the term used to categorize the migration of people who migrate due to new or established family ties, and it encompasses several sub-categories: reunification with a family member who migrated earlier (a person with subsidiary protection is also entitled to (re)unite with family members); family accompanying a principal migrant; marriage between an immigrant and a citizen; marriage between an immigrant and a foreigner living abroad; and international adoptions.

In general, data on family migration are sparse and family (re)unification programmes are the predominant means to collect such data. These programmes were developed to ensure the right to a family enshrined in Article 16 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. Data on family migration are based on visas and residence permits issued to family members, as well as population registers.

Definitions

Family migration as a general concept covers family reunification, family formation, accompanying family members of workers, and international adoption. The following are key terms and concepts:

Family reunification/reunion is “the right of non-nationals to enter into and reside in a country where their family members reside lawfully or of which they have the nationality in order to preserve the family unit” (IOM, 2019).

Family formation refers to the situation in which “a resident, national or foreigner, marries a foreigner and sponsors that individual for admission or for status change” (OECD, 2019).

Accompanying family “means family members Configuration[who] are admitted together with the principal migrant” (OECD, 2019).

International adoption is where a “resident, national or foreigner, adopts a child of foreign nationality resident abroad” (OECD, 2019).

Principal/primary/main applicant is “in the migration context, the person who applies for refugee or other immigration status and under whose name the application is made.” (IOM, 2019).

Dependent is “in the migration context, any person who is granted entry into a State for the purpose of family reunification on the basis of being supported by a “sponsor” with whom the individual has a proven family relationship" (IOM, 2019).

Members of the family are “persons married to a migrant or a national, or having with them a relationship that, according to applicable law, produces effects equivalent to marriage, as well as their dependent children or other dependent persons who are recognized as members of the family by applicable legislation or applicable bilateral or multilateral agreements between the States concerned, including when they are not nationals of the State” (IOM, 2019).

The scope of family reunification depends on national law. For example, some countries may include same-sex partners (registered or married) or unmarried partners, whereas others may not (European Migration Network, 2017). Thus, the definition of whom family members can comprise varies across countries.

Transnational families “are families who live apart, but who create and retain a ‘sense of collective welfare and unity, in short “familyhood”, even across national borders’” (Bryceson and Vuorela, 2002 in ACP, 2012).

Recent trends

Data on family migration in developing countries are either sparse or scattered, due to a lack of capacity or political will to collect data (see data strengths and limitations below). However, family migration data are available for countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) area.

According to preliminary estimates, in 2022, permanent-type migration flows to OECD countries reached 6.1 million, an approximate increase of 26 per cent from 2021, and 14 per cent from 2019 (OECD, 2023).

The number of migrants who moved to OECD countries for family reasons increased by approximately 15 per cent from 1.9 million in 2021 to 2.2 million in 2022, exceeding the 2 million recorded in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2023).

On the national level, the countries receiving the highest numbers of new family migrants in 2022 were the United States of America (723,000), the United Kingdom (242,000), Canada (217,000), Australia (102,000) and New Zealand (72,000) received the highest numbers of new family migrants in 2022 (OECD, 2023). Although this is an increase of 14 per cent compared to 2021, it continues to be lower than in 2019 (ibid.). The United Kingdom and Canada received the second and third highest numbers of family migrants respectively in 2022, and family migration to both destinations increased significantly compared to 2021 and 2019 (OECD, 2023). The United Kingdom admitted 242,000 family migrants in 2022, approximately 20 per cent more than the previous year, and a 72 per cent increase from 2019 (ibid.). Canada received 217,000 family migrants in 2022, 32 per cent more than in 2021, and 18 per cent more than in 2019 (ibid.). Relative to 2019, other countries also admitted more family migrants with increases of 229 per cent in New Zealand, 78 per cent in Mexico, 51 per cent in Finland, and 29 per cent in Estonia (ibid.).

The increase in family migration is mainly due to the increase in family members accompanying migrant workers. In 2022, accompanying family represented 27 per cent of all family migration to OECD countries, whereas the share was only 17 per cent in 2019 (OECD, 2023). The OECD countries with the highest inflows of family members accompanying migrant workers in 2022 were the United Kingdom (154,900), United States of America (141,900), Canada (119,800) New Zealand (63,000) and Australia (48,000) (OECD, 2023).

Family reunification is possible for all migrants in 42 per cent of MGI countries, and possible for some foreign residents in 53 per cent of them (MGI Database, 2024).¹ There are regional variations with family reunification being an option for all migrants in 67 per cent of the MGI countries in Oceania, 45 per cent in Europe, 41 per cent in both the Americas and Africa, and 37 per cent in Asia (ibid.).

¹Note that this analysis is based on the Migration Governance Indicators (MGI) data from 100 countries.

Data sources

Both flow and stock data on family migration are predominantly based on national administrative records. Family migration flow data are derived from entry clearance visas (ECV), first residence permits or population registers for family reasons. Stock data on family migration are based on stock of permits or stock of long-term residents. Some countries combine administrative and specific survey data on family migration, e.g. the international passenger survey (IPS), to augment the quality of data. Data on family migration are also collected via such sample surveys as annual population surveys, labour force surveys or income and living conditions surveys. Data collected via individual surveys or ethnographic studies enable collection of granular data to better understand the transnational family arrangements across borders.

The following are databases that consolidate flow or stock data on family migration:

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) consolidates inflow data on family, work and humanitarian migration. The OECD dataset on permanent immigrant inflows is derived from Eurostat (see below) and non-EU countries. The dataset is updated on a biannual basis.

OECD also produces statistics on permanent migration inflows in the OECD area, based on the aforementioned dataset, which are presented in the OECD’s International Migration Outlook. The report also presents estimates on family migration for OECD countries and is updated annually.

Eurostat, the Statistical Office of the European Union compiles data on asylum and managed migration primarily based on administrative sources provided by EU Member States’ national statistical offices, interior ministries or related immigration agencies, as well as by Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland. The database on asylum and managed migration presents the following datasets:

- First permits issued for family reunification with a beneficiary of protection status

- First permits issued for family reasons, by reason, length of validity and citizenship

- Change of immigration status permits, by reason and citizenship

- Admitted family members of EU Blue Card holders, by type of decision and citizenship

- EU Blue Card holders and family members, by member state of previous residence

- Permits valid at the end of the year for family reunification with a beneficiary of protection status

The aforementioned datasets are disaggregated by sex and age. Data are predominantly updated on an annual basis.

The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) measures migrant integration policies, including for those who come for family reasons. Similar to their previous rounds, MIPEX 2020 also measures how easily immigrants can reunite with their family members. Among OECD countries, data on family reunion – which were last updated in 2020 – are available for Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States of America.

Back to topData strengths & limitations

In light of the current political climate, in which family-based migration in some countries is discussed in connection to irregular migration or in the context of it being a burden to the social system of a host country, granular data on family migration are of special importance to deconstruct these particular myths with data-driven deliberations.

The existing data sources on family migration are valuable baselines, but further enhancement in data collection and harmonization methodologies is essential. In pursuit of these improvements there are limitations that hinder the process, including the following:

There is no global comparable database on family migration, which covers all countries and areas of the world. This is due to a lack of data from most developing countries. Data are missing due to a lack of capacity to collect, process and disseminate data on family migration in these countries. Even when data are available, it is often challenging to integrate and harmonize datasets of diverse origins because of inconsistent methodological frameworks.

There is still little known about the recent dynamics of family migration and about the impact of migration policies in shaping it (OECD, 2017). This is despite the availability of family migration data in some regions of the world. Moreover, the evidence-base regarding the socio-economic demographic characteristics of family migration in some countries has not been updated. For example, in the United States, the most recent surveys on socio-demographic characteristics of family migrants date from the 2000s (ibid.).

Statistics derived from administrative records do not portray the complete picture of the flow of family migrants (GMG 2017). This is because, although administrative data sources enable the production of estimates on family migration, statistics derived from population registers and issuance of residence permits refer to administrative records rather than people (ibid.). For example, if the permit granted to the head of a family covers her or his dependents, the number of issued residence permits over a year will not be equivalent to the number of family migrants. Some countries are undertaking initiatives to tackle this issue. They tend to combine different data types, namely survey data and administrative records, to improve the quality of migration data.

Data on transnational familyhood are scarce. Despite the growing importance of this type of family arrangement in recent years, there is still limited knowledge on the scale and dynamics of this type of family arrangement in a migration context. Evidence-based policy is needed to ensure the migration of a family member does not need to lead to those left behind suffering.

Data on family emigration are currently incomplete because of the most countries’ limited capacity or lack of political will to collect data on family emigration. Thus, policy makers lack a sufficient evidence base to facilitate family emigration processes.

Further reading

| Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) | |

|---|---|

| 2023 | International Migration Outlook, OECD, Paris. |

| 2022 | International Migration Outlook, OECD, Paris. |

| 2021 | International Migration Outlook, OECD, Paris. |

| 2019 | International Migration Outlook, OECD, Paris. |

| 2017 | Making Integration Work: Family Migrants, OECD, Paris. |

| International Organization for Migration (IOM) | |

| 2019 | World Migration Report 2020, IOM, Geneva. |

| Castro Martin, T., J. Koops, and D. Vono de Vilhena (eds.) | |

| 2019 | Migrant Families in Europe: Evidence from the Generations & Gender Programme. Discussion Paper No. 11, Berlin: Population Europe. |

| Niskanen Center | |

| 2017 | Overview of Family-Based Immigration and the Effects of Limiting Chain Migration, Niskanen Center, Washington, D.C. |

| Fan, C. and M. Sun and S. Zheng | |

| 2011 | Migration and split households: A comparison of sole, couple, and family migrants in Beijing, China, Environment and Planning A, 43: 2164-2185. |

| European Migration Network (EMN) | |

| 2017 | Family Reunification of Third-Country Nationals in the EU plus Norway: National Practices, EMN, Dublin. |

| Confederation of Family Organizations in the European Community (COFACE) | |

| 2012 | Transnational Families and the Impact of Economic Migration on Families, COFACE, Brussels. |