Future migration trends

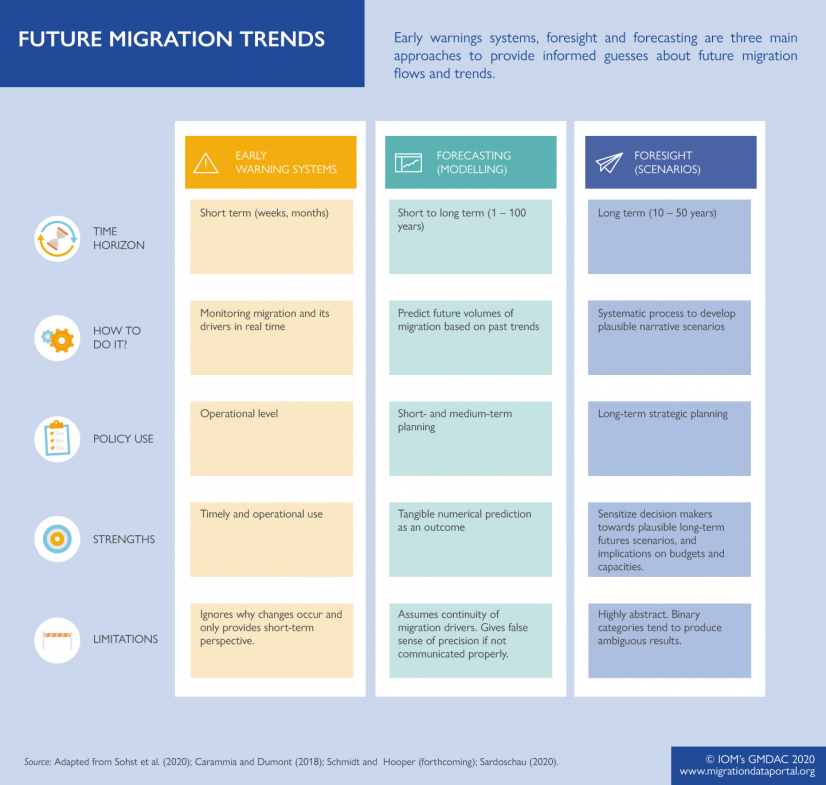

Anticipating future migration flows encompasses an increasingly diverse field of approaches. Early warnings systems, foresight (scenarios) and forecasting are the three main approaches intended to provide informed guesses about future migration flows and trends. These approaches can provide crucial information for policymakers to anticipate future challenges and adjust policies, design programmes and allocate resources. Rather than providing an accurate prediction of future flows, many projects aim to highlight the inherent uncertainty of future migration and work towards greater preparedness and resilience through setting up contingency plans for various future possibilities. All approaches hinge on the underlying data that they use, such as experts, administrative data, surveys or censuses. Predictions in the field of migration appear particularly difficult given the complexity and diversity of the migration processes, the limited availability and quality of data, and the limited understanding of the migration drivers.

Definitions

Early warning systems

Early warnings systems rely on quantitative and qualitative data to monitor potential drivers and movements of populations in real time to provide short-term estimations in fast-changing contexts (Carammia and Dumont, 2018). The systems allow decision-makers to allocate budgets and resources preventively (Schmidt and Hooper, forthcoming). Early warning systems may establish pre-defined warning thresholds, that when exceeded, kick off a mechanism of coordinated chain action by various stakeholders (Bijak et al., 2017).

Forecasting

Migration forecasting attempts to predict future migration flows and trends using, traditionally, quantitative modelling methods with a medium and long-term horizon (Bijak, 2011; Disney, 2015). This approach statistically models future migration trends based on quantitative data from the past. This type of modelling is possible when rich numerical data are available, for example, on past inflows and outflows, policy changes, as well as various other migration factors and drivers. (Sohst et al., 2020; Bijak, 2016).

Foresight

This approach tends to use qualitative scenario methods to describe future migration flows and trends. Migration scenarios are qualitative narratives about the future of migration that examine possible structural changes and their consequences for migration (Vezzoli et al., 2017; De Haas et al. 2010). They can be understood as thought experiments of the type “What if…?”. Scenarios are typically developed by a group of experts engaging in systematic group discussions (Sohst et al., 2020).

Foresight approaches largely rely on subjective opinion and judgment of experts. As such methods do not have to take into account statistical information about trends, it can be used when past data are limited, not comparable or infrequent. Some approaches have attempted to combine qualitative and quantitative information in forecasting, for example by using expert-based probabilistic methods (Lutz et al., 1998), or – more recently – Bayesian statistical approaches (Bijak, 2011; Bijak and Wiśniowski, 2010; Bijak and Bryant, 2016), applied recently at the global level (Azose et al., 2016; Sander et al., 2013).

Recent trends

Global migration projections vary in their predictions of future migration flows and trends (Buettner and Muenz, 2016). Researchers at the Vienna Institute of Demography, combining expert opinion and forecasting, project global flows of international migrants for five-year period for 2015-60 for three different scenarios. According to their estimations, the number of international migrants in those decades will remain almost constant, reaching a peak in 2040-45 and then a slight decline (Sander et al., 2013). The lower bound scenario estimates 29 million international migrants across the five-years interval, the medium scenario 33 million, and the upper bound scenario 50 million. The estimated global levels vary by region. In the medium scenario, researchers project that there will be 8 million international migrants in Europe and North America respectively during 2055-60; 5 million in West Asia; 4 million in Africa; 3 million from the former Soviet Union countries; and approximately 1 million in Oceania, Latin America, East Asia, South-East Asia and South Asia, respectively.

The 2019 estimates from the United Nations Population Division assume constant net migration levels between 2019 and 2100. Net migration can be understood as “the difference between the number of immigrants arriving in and the number of emigrants leaving from a particular country during a certain period of time” (UN DESA, 2019). At the global level, the sum of such migration levels is equal to zero, meaning that the number of immigrants arriving in all countries is the same as the number leaving from those same countries. According to the report, it is plausible to believe that migration levels will be constant until 2100 because migration flows “have historically been small and have had little impact on the size and composition of national populations.”

Previous estimates from the UN, by contrast, assumed that net international migration would, by 2095-2100, reach half the levels projected for 2045-50 (UN DESA, 2019). By relying on this assumption, and by interpreting net migration figures as gross immigration, researchers estimated that in the 2010-15 period the recorded total net immigration for the world was 25 million, and also estimated a decrease to 16.6 million during 2020-25 and a further reduction to 13.7 million across five year periods between 2030-50 (UNDP in Buettner and Muenz, 2016). In a comparison exercise of the UN and the Vienna Institute of Demography estimates, researchers concluded that while UN estimates are smaller — as expected because they account only for gross immigration and not gross migration — trends are quite similar (Buettner and Muenz, 2016).

At the national level, many governments conduct migration forecasts. Such forecasts vary on their inclusion of scenarios, number of migrant subgroups, projection period, assumptions, and methodology (Cappelen et al., 2015). Some of the examples that are publicly accessible include Canada, Germany and Australia.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2017) developed global migration scenarios narratives for 2030. In the scenario characterised by a successful implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, the change in the average annual global migration flows over 2015-30, as compared to 2000-15, is expected to increase above 3.3 per cent but below 4 per cent. On the contrary, in a scenario of conflict and unilateral and fragmented international cooperation, future flows would decrease below 3 per cent over 2015-30, as compared to 2000-15.

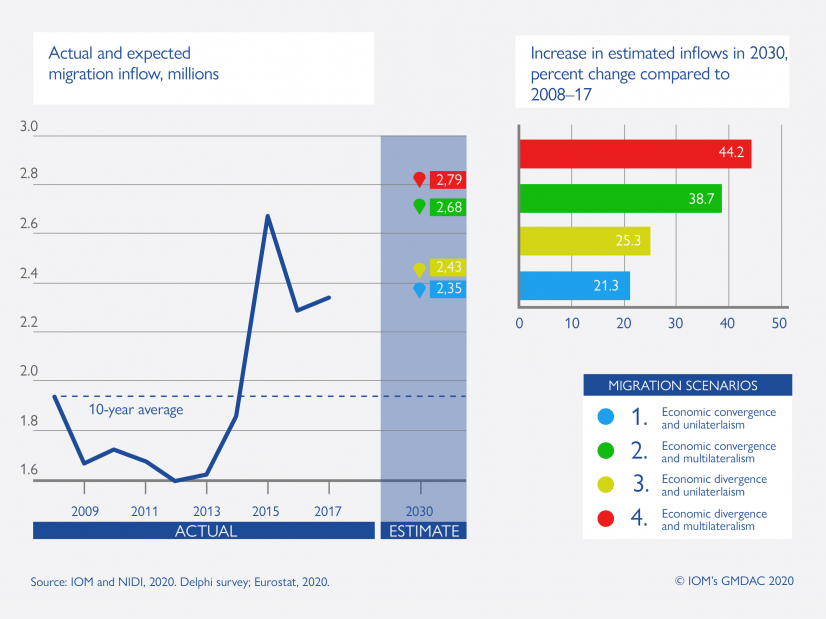

In an exploratory study, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM)’s Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (GMDAC) and the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute combined two separate methodological approaches: migration scenarios and a Delphi expert survey (Acostamadiedo et al., 2020). According to the results, total immigration flows to the European Union (EU) in 2030 might increase between 21 and 44 per cent compared to the average yearly immigration flows recorded between 2008 and 2017.

Data sources

Early warning systems

- The International Organization for Migration’s Displacement Tracking Matrix, implemented in more than 70 countries, collects data that can be used for early warning purposes;

- The Early Warning and Preparedness System from the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) provides a regional outlook with an analysis of asylum trends and push–pull factors, as well as risk analysis on a monthly basis;

- Multiple EU Members States use predictions of inflows of asylum seekers (European Migration Network, 2014). The sources are based on the analysis of quantitative data on asylum trends, expert knowledge, qualitative border intelligence, media, and contextual data on routes, as noted by Bijak et al. (2017). According to these researchers, while the methods are not very complex, their strength relies in the myriad of sources in which they rely on and that allows to quantify inflows several times a year. The Swedish and Swiss models are among the most consolidated in Europe and some researchers have documented the main steps in the process, as described below (Carammia and Dumont, 2018; Bijak et al., 2017).

- The approach from the Swiss State Secretariat for Migration can be regarded as an expert-based model and is focused in year-ahead estimations of asylum flows (Bijak et al., 2017). The process starts by assessing the push factors in sending countries. Country experts are asked to justify and provide an estimate of future flows. Using a wide range of sources, the analysis complements with data on changes along the migratory routes to Europe. Then, pull factors including economic, asylum policy and the welfare arrangements issues is incorporated into the analysis. Finally, analysts put the information together and produce scenarios that vary in the estimated flows.

- The model from the Swedish Migration Agency is also focused on asylum applications, with a horizon of one to two years, and uses a mix of qualitative and quantitative sources (Bijak et al., 2017). The data cover push and pull factors of migration flows, migration routes, asylum policies. Experts are involved in the process by quantifying the qualitative insights and then a forecast of asylum flows is derived.

Forecasting

Quantitative migration forecasts are often produced by National Statistical Offices and university research institutes and most often focus on a particular region or country. There are a few large providers of population projections at the global level that include projections of international migration:

- The United Nations Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs has the longest record of production of global population estimates and projections until 2100, including international migration assumptions. Since 1951, it has produced 26 rounds of its global population estimates and projections. To date, the latest version of its series of World Population Prospects (WPP) is the 2019 Revision (UN DESA, 2019). WPP currently covers 233. countries and territories, making it the geographically most complete dataset.

- The Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital provides projections of net migration rates per country until the year 2100 based on different scenarios and assumptions (Lutz, et al. 2018).

- The US Census Bureau produces net international migration estimates covering 220 countries and territories until the year 2060.

Other datasets have been made available for particular regions, for example, the European Union's EUROPOP, produced by Eurostat, is the most recent edition covering the period between 2018 and 2100 (EUROPOP, 2018). These datasets from Eurostats provide information at national level across 29 European countries: for each EU-28 Member State and Norway.

Foresight

Data sources for qualitative migration scenarios include:

- The Global Migration Futures project developed systematic exercises with international migration experts, stakeholders and scholars to examine potential future political, economic, social, technological and environmental changes at the global level and their consequences for migration.

- The Future of International Migration to OECD Countries report analysed key migration drivers (cooperation at the international level, economic convergence versus economic divergence in per capita incomes between OECD and non-OECD countries, and open versus restrictive migration policies). The study prepared four different scenarios of migration by looking at key determinants of global migration flows by 2030.

- The Strategic Foresight Unit from the OECD has explored plausible future changes of potentially great significance for migration and integration policy in OECD countries.

- Future immigration scenarios to the EU. IOM’s GMDAC, in partnership with the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute (NIDI), examined the potential and limitations of using expert opinion on future migration. The pilot study combined two approaches – migration scenarios and Delphi expert surveys – to assess the implications and uncertainty of common migration scenarios for the EU in 2030. The data collected can be explored with a visualisation tool.

- The UK Government’s Foresight Project developed global migration scenarios with a 50-year frame. The key migration drivers identified were global migration opportunities linked to high global economic growth versus low global economic growth, and the level of inclusion versus exclusion of political, social and economic governance regimes at a local level.

Data strengths & limitations

Early warning systems

- Operational level policy decisions: Early warning system have the potential to change the decision-making from a reactive to a pro-active manner (Bijak et al., 2017).

- Early warning system do not provide information about the drivers of migration and do not contribute to the explanation of migration trends.

Forecasting

- Explicit assumptions and guiding theory: The data-driven approaches tend to be explicit in how assumptions within a model can affect future migration flows, that is, they are transparent on how the guiding theory is used to estimate future flows (Sardoschau, 2020). Forecasts also provide a tangible numeric estimate of future flows which is easy to understand.

- Long time span: Unlike other methods, they are less limited in the time span they can cover since, in principle, past data trends can be extrapolated for many years in the future (Sardoschau, 2020).

However, forecasting is notoriously difficult and unreliable (Bijak, 2016). There are many reasons why migration forecasting is such a difficult task:

- Lack of uniform concepts and definitions for migration: For example, many countries define migration flows differently. In principle, migration involves relocating across an international boundary for a period of time, but the exact operationalization of this concept in practice varies.

- There are many—and unpredictable—drivers of migration: The diversity of motives behind migration flows and the emergence of new types of migration make it difficult to predict. (Bijak, 2016).

- Forecasts are based on different, imperfect and interacting assumptions: Migration forecasting relies on assumptions regarding demographic dynamics, the political, environmental and socioeconomic changes, as well as migration policies. The sheer number of push and pull factors (determinants) and drivers of mobility and immobility, all interacting with one another, makes a comprehensive explanation of migration processes anything but possible. In other words, models are vulnerable to shocks that move away from their assumptions (Sardoschau, 2020).

- Underlying data may be incomplete and not reliable: In many developing countries, empirical evidence about past and current migration flows is almost entirely missing, and for a number of developed countries, data are also incomplete or unreliable (Buettner and Muenz, 2016).

Foresight:

- Educational tool: Migration scenarios allow those that participate in the scenario creation process to question assumptions on migration and imagine, anticipate and prepare for uncertain future migration trends. (Vezzoli et al., 2017).

- Long-term thinking: Involving experts in systematic, iterative and participatory processes to anticipate the future of migration has the potential to reduce short-sighted policies – especially if policymakers are part of the process. This approach is useful to facilitate strategic long-term thinking among executive decision makers rather than providing operational input (Acostamadiedo et al., 2020).

Despite these benefits, scenarios have shortcomings.

- Disagreement among experts: There is often large disagreement and high uncertainty among experts on how migration drivers will affect future migration flows (Acostamadiedo, et al. 2020).

- Ambiguous impact of migration drivers: The migration scenario reports sometimes produce ambiguous results on the impact of future migration drivers on flows (Sohst et al. 2020). The theoretical model in qualitative scenarios tends to be less explicitly expressed in contrast to quantitative forecasts (Sardoschau, 2020).

- Difficulty translating input to policy: Migration scenarios are most useful for those that participated in the process, but it is more challenging to translate the scenario narratives into actionable policy. Important attempts have been made to overcome this limitation (Szczepanikova and Van Criekinge, 2018).

Further reading

Acostamadiedo et al.

| 2020 | Assessing immigration scenarios for the European Union in 2030 – Relevant, realistic, reliable?

International Organization for Migration, Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographics Institute, Geneva. |

Sohst et al.

| 2020 |

The Future of Migration to Europe: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Migration Scenarios and Forecasts. International Organization for Migration, Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographics Institute, Geneva. |

Azose, J. and Reftery, A.

| 2015 | Bayesian Probabilistic Projection of International Migration. Demography 52(5): 1627-1650. |

Bijak, J.

| 2011 | Forecasting International Migration in Europe: A Bayesian View. Springer. |

| 2016 |

Migration forecasting: Beyond the limits of uncertainty. Global Migration Data Analysis Centre, Data Briefing Series, Issue No. 6. |

Bijak, J. and Bryant, J.

| 2016 |

Bayesian demography 250 years after Bayes. Population Studies. |

Bijak, J. and Wiśniowski, A.

| 2010 |

Bayesian forecasting of immigration to selected European countries by using expert knowledge. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 173(4), 775-796. |

Bijak, J., Forster, J. and Hilton, J.

| 2017 |

Quantitative assessment of asylum-related migration: A survey of methodology. European Asylum Support Office. |

Buettner, T. and Muenz, R.

| 2016 |

Comparative Analysis of International Migration in Population Projections. Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD). Working Paper 10. |

Cappelen, Å, Skjerpen, T. and Tønnessen, M.

| 2015 |

Forecasting Immigration in Official Population Projections Using an Econometric Model. International Migration Review. Volume 49 Number 4. |

Carammia, M. and Dumont, J.

| 2018 |

Can we anticipate future migration flows? OECD/EASO Migration Policy Debate N.16. |

De Haas, H., Vargas-Silva, C., and Vezzoli, S.

| 2010 |

Global Migration Futures: A conceptual and methodological framework for research and analysis. International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford. |

Disney, G. et al.

| 2015 |

Evaluation of existing migration forecasting methods and models. Report for the UK Migration Advisory Committee. ESRC Centre for Population Change, University of Southampton. |

European Migration Network

| 2014 |

Ad-Hoc Query on Forecasting and Contingency Planning Arrangements for International Protection Applicants. European Commission. |

Lutz, W. et al.

| 2018 |

Demographic and Human Capital Scenarios for the 21st Century: 2018 assessment for 201 countries. EUR 29113 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

| 2017 |

Four possible scenarios for international immigration in 2030. In Perspectives on Global Development 2017. International Migration in a Shifting World. OECD Publishing Paris. |

Raymer, J., and Wiilekens, F.

| 2008 |

International migration in Europe: Data, models and estimates. John Wiley & Sons. |

Sander, N., Abel, J. and Riosmena, F.

| 2013 |

The Future of International Migration: Developing Expert-Based Assumptions for Global Population Projections. Vienna Institute of Demography 7/2013. |

Sardoschau, S.

| 2020 |

The Future of Migration to Germany. Assessing Methods in Migration Forecasting. DeZIM Project Report #DPR 1|20 Berlin. |

Sohst et al.

| 2020 |

A Systematic Literature Review of Migration Scenarios and Forecasts. |

Szczepanikova, A. and Van Criekinge, T.

| 2018 |

The Future of Migration in the European Union: Future scenarios and tools to stimulate forward-looking discussions. EUR 29060 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ISBN 978-92-79-90207-9, doi:10.2760/000622, JRC111774. |

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affair – UN DESA

| 2019 |

Vezzoli, S., Bonfiglio, A. and De Haas, H.

| 2017 |

Global migration futures - Exploring the future of international migration with a scenario methodology. University of Oxford, International Migration Institute Working Papers, 135. |