Back to top

Definition

The World Bank’s 2017 Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals groups recruitment costs into three main types of costs:

1. Costs to comply with laws and regulations of origin and destination countries (such as obtaining work permits or medical check-ups);

2. Fees paid to recruitment agents; and

3. Internal and international transportation costs.

An additional important concept to better understand recruitment costs is the recruitment cost indicator (RCI), which measures how many times more than their monthly foreign earnings migrant workers pay to secure a job overseas (KNOMAD, 2016).

Recent trends

According to the analysis of the Migration Cost Surveys (2016-2017) carried out by the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration Development (KNOMAD) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), the recruitment cost indicator tends to be higher for low-income migrant workers (Ratha et al., 2018). In addition, these migrant workers, who incur high recruitment costs, are paid less and more irregularly than what is contractually promised (ibid.). Thus, vulnerable migrant workers are the ones who experience higher costs.

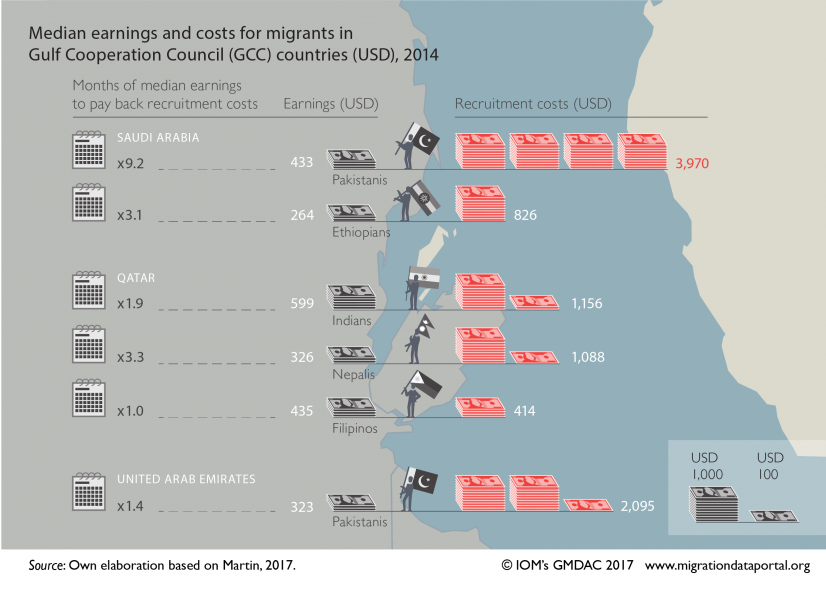

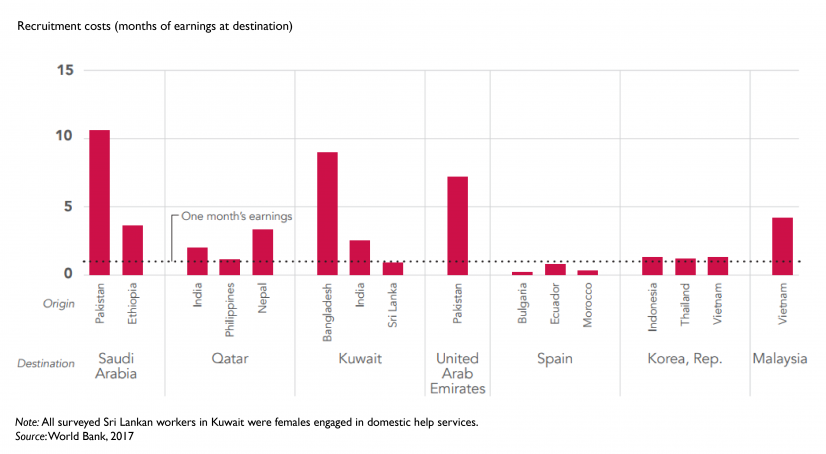

As the chart below shows, recruitment costs vary considerably across different migration corridors and are often higher than one month’s earnings at destinations (Abella and Martin, 2014).

For example, migrant workers from various countries of origin migrating to Spain and the Republic of Korea pay recruitment costs amounting to about one month’s earnings (or about 8 per cent of annual earnings). However, migrants from Pakistan working in low-skilled jobs in Saudi Arabia pay recruitment costs of approximately 11 months’ earnings (or about USD 4,400 at 2014 rates) (Martin, 2016).

Back to top

Data sources

Several data sources collect information on migrant recruitment costs at the global and regional levels.

Global level data collection

KNOMAD and the ILO conducted two series of Migration Cost Surveys (MCS):

The MCS (2015-2016) covers 10 bilateral migration corridors and consists of 7 surveys. The 2015 dataset includes the following corridors: Pakistan to Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia to Saudi Arabia, India to Qatar, Nepal to Qatar, Philippines to Qatar, Viet Nam to Malaysia and Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador to Mexico (non-recruited workers).

The MCS (2016-2017) consists of 5 surveys from 9 following bilateral migration corridors: India to Saudi Arabia, Philippines to Saudi Arabia, Nepal to Malaysia, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan to Russia (non-recruited workers) and West African countries to Italy (non-recruited workers).

KNOMAD and ILO also conducted a comparative pilot survey on recruitment costs in 2014 to 2015. In particular, they collected information from interviews with migrant workers who were employed in destination countries (the Republic of Korea, Kuwait and Spain) and with migrants returning from jobs abroad to origin countries (Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Pakistan and the Philippines) from jobs in Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Martin, 2016). The results of the first survey were published in 2014 (Abella and Martin, 2014). Other data collected under the same study have been published in several documents, including a conference background paper (Martin, 2016).

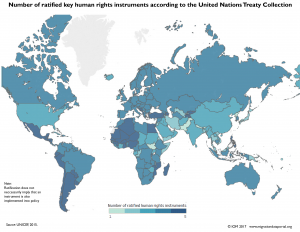

Goal 10 Target 7 of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) encourages States to facilitate "orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people". To measure countries' progress towards this target, the SDG agenda proposes:

“Measuring recruitment costs borne by employees as a proportion of the monthly income earned in the country of destination” (SDG 10.7.1).

Therefore, in collaboration with several stakeholders and international agencies, the ILO and the World Bank drafted new methodology guidelines to measure recruitment costs and presented it in 2018 in consultation workshops for National Statistical Offices. The guidelines recognize the need for data on recruitment costs of all types of employees while simultaneously stressing the importance of disaggregated data. Since past KNOMAD-ILO surveys show that low-skilled and semi-skilled workers pay relatively high recruitment costs, such disaggregated data allow the situation of the most vulnerable to be highlighted (KNOMAD-ILO, 2018). Due to this development in methodology, the UN reclassified the indicator from Tier III to Tier II in November 2018.

Regional level data collection

Asia: The Open Working Group on Labour Migration and Recruitment coordinated by the Migrant Forum in Asia has published data on recruitment costs of workers from a number of countries (See: Open Working Group on Labour Migration and Recruitment, 2014).

Americas: The Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC, 2013) collected data on the recruitment costs of Central and South American workers (from Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia, Dominican Republic) in the United States (US). The Centro de los Derechos Migrante (CDM, 2013) and the US Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2015) have also collected data on the recruitment costs of Mexican “guest” workers in the US. However, data that GAO used in its study on programmes were not representative of all “guest” workers”.

Europe: There are several studies on recruitment costs in Germany including Mühlemann and Pfeifer, 2013 and Mühlemann, Pfeifer and Wenzelmann, 2015.

Back to top

Data strengths & limitations

The available yet few data that exist on recruitment costs show the extent to which workers are exploited and therefore help policymakers design evidence-based policies.

As recruitment fees are often illegally imposed, measuring such costs in surveys has limitations:

Hidden costs are not counted - Most available data on recruitment costs focus on the costs paid to recruitment agents to obtain a job abroad and on the travel-related costs to reach the job location (visa, documents and transportation). However, there are also i) the opportunity costs of wages not earned while training and preparing to go abroad and ii) the social costs associated with separation from family and friends, and restrictions on rights while employed abroad. If these two dimensions were included, recruitment costs would be even higher (Martin, 2017).

Data are provided by workers, not employers - Most data on recruitment costs are obtained by interviewing migrant workers. Collecting data on recruitment costs by interviewing recruiters and employers could contribute to improved recruitment costs estimates and to a better understanding of how recruitment dynamics work (Martin, 2016).

Back to top