Migration Data in the Southern African Development Community (SADC)

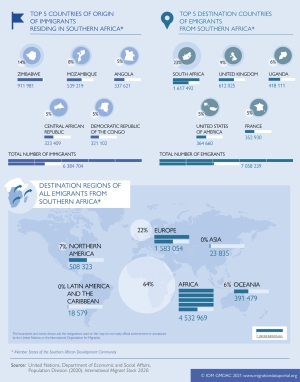

Migration to and from countries in Southern Africa1 is driven largely by the pursuit of economic opportunities, political instability and increasingly, environmental hazards. In a region with an estimated population of 363.2 million people and 6.4 million international migrants at mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020), a few countries serve as the economic pillars of the region. Industrial developments, the mining sectors in South Africa, Botswana and Zambia, and the oil wealth of Angola have been magnets for both skilled and unskilled labour migrants from within the region and elsewhere. An estimated 2.9 million migrants resided in South Africa at mid-year 2020 (ibid.), the most industrialized economy in the region and a particularly attractive destination for those in search of education and better opportunities.

In the eastern part of the region, Comoros, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique and other countries are frequently affected by natural hazards such as cyclones and flooding (IDMC, 2019). Slow-onset disasters such as drought impact the lives and the migration patterns of millions in Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and Zambia (SADC, 2019). Fluid, circular migration patterns and maintenance of socioeconomic networks between rural places of origin and urban centers have become increasingly common strategies for resilience in this diverse region (FAO and CIRAD, 2017).

Recent trends

- COVID-19:Based on the rapidly evolving epidemiological conditions across various parts of the region, COVID-19 related travel measures continue to keep regional mobility and migration curtailed. The measures include the withdrawal of exemptions for nationalities previously visa-exempted and the invalidation of visas for nationalities from COVID-19 hotspots. At the same time, several countries have automatically extended visa and permit extension to those already regularly in country before the pandemic, showing some leniency for stranded migrants and visa overstayers (IOM, 2020). As of 3 March 2021, 24 per cent of the 329 Points of Entry (PoE) assessed by IOM in the Southern Africa region were fully closed, 68 per cent were partially or fully operational and the status of 8 per cent unknown (IOM, 2021). The impact of COVID-19 on human mobility is expected to have far-reaching socioeconomic consequences including on remittance flows to the region.

- HOST COUNTRIES: South Africa (2.9 million), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (952,871) and Angola (656,434) were estimated to be the three countries hosting the highest number of international migrants in the sub-region at mid-year 2020 (UN DESA, 2020).

- DESTINATION COUNTRIES: In absolute numbers, most migrants from Southern Africa move to other countries within Africa. With the exception of migrants from Madagascar, Mauritius and South Africa, the top destination countries for migrants from the other thirteen countries in the sub-region are in Africa (ibid.).

- LABOUR MIGRATION: The opportunities available for semi-skilled labour including in sectors such as construction, mining and services are major migration drivers throughout the region. The United Republic of Tanzania and South Africa attract high-skilled labour in financial services. Upskilling trends are on the rise among semi-skilled migrants to South Africa, while commercial agriculture absorbs the large majority of low-skilled migrant labour to the country (AU, 2017; UNCTAD, 2018: 81-85).

- REMITTANCES: Countries in Southern Africa received an estimated 7 billion USD in remittances in 2019 (World Bank, 2020a). Remittances sent by migrants are a significant source of capital in most Southern African countries (Truen et al., 2016: 9), but the costs of receiving remittances continue to be among the highest globally (GMDAC analysis based on World Bank, 2020b). In 2019, the Democratic Republic of the Congo received the highest amount of remittances in the sub-region in absolute terms. As a percentage of GDP, Lesotho was the highest recipient of remittances in the sub-region in 2019 (World Bank, 2020a). Aggregated projections for Southern Africa are currently not available, but remittances to sub-Saharan Africa are projected to decline by 8.8 per cent by the end of 2020 and by another 5.8 per cent in 2021 due to COVID-19 (Ratha et. al., 2020). In Namibia, where 98 per cent of urban residents maintain rural ties, migrants in urban areas send cash remittances to their relatives in rural areas in exchange for agricultural produce (Pendleton et al., 2014: 195-201).

- CROSS-BORDER TRADE (CBT): Revenue obtained through CBT is often the primary source of income for small-scale traders in the region, notably for women and young people. Although accurate data on the volume of (informal) CBT trade are limited, estimates range between 50 and 60 per cent of total intra-Africa trade (TRALAC, 2018).

- FEMALE MIGRANTS: Seventy per cent of informal CBT is undertaken by female migrants, and accounts for as much as 30 to 40 per cent of SADC trade (UNCTAD, 2018: 85). In Namibia, independence from the more male-dominated rural social systems is an important driver for female rural-to-urban migration (Pendleton et al., 2014: 195).

- INTERNAL MIGRATION: Non-disaster-related Internal migration trends in the sub-region are largely rural-to-urban in nature with education and employment being key motivating factors. Rural migrants tend to come from more educated families, and most migrants within the region fall between the ages of 30 and 40. (FAO and CIRAD, 2017).

- REFUGEES: As of December 2019, 523,734 refugees originated from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, making it the country of origin of the highest number of refugees in the region and the eleventh highest globally. 96 percent of these refugees were hosted in sub-Saharan African countries (UNHCR, 2020). As a percentage of the international migrant stock residing in their countries, the United Republic of Tanzania (64 per cent) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (55 per cent) continue to host the highest numbers of refugees in the region (UN DESA, 2020).

- INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT: Protracted internal conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo newly displaced 1.7 million people in 2019 (IDMC, 2020). A total of more than 5.5 million people lived in internal displacement due to conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by the end of 2019, making it the country with the third highest number of people displaced by conflict globally (ibid.). In 2019 alone, nearly 1 million people were newly displaced by disaster in the sub-region (ibid.).

Past trends in migration

1869 – 1910: Colonial period & institutionalized labour migration systems

- This era was dominated by increasingly institutionalized, colonial exploitation of migrant labour. Miners were drawn largely from Mozambique, Lesotho and Eswatini as well as Botswana, Malawi and Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia under the British South African Company).

- 1869 – Diamonds discovered in Kimberley, South Africa, instigate large-scale migrations to the country

- 1880s – Final period of indentured migration of Indians to Mauritius

- 1885 – The German colonial administration in Tanzania establishes systems of (forced) migrant labour which preserves ties to communities of origin

- 1901 – Rand Native Labour Association established to institutionalize a (forced) migration labour system in Southern Africa

- 1906 – Colonial systems established to support the labour mobilization for diamond mines and railroads in the Congo Free State (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- 1910 – Establishment of the oldest customs union in the world, the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) among 5 countries, South Africa, Namibia, Swaziland, Lesotho and Botswana

1948 – 1990: Apartheid era

This era saw major civil wars fought across a number of Southern African states over several decades, including Angola, Mozambique and Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia). Black populations in South Africa, former Rhodesia and Namibia were generally oppressed under the apartheid regime. Migrant labour routes expanded beyond South Africa’s Kimberley and Witwatersrand mines to Zambia and Botswana.

- 1948 – Apartheid begins in South Africa

- 1960s – Copper mining in Zambia draws migrants to Zambia

- 1970s – Diamonds discovered in Botswana also attract migrant labour

- 1972 – Protracted insurgency begins in Rhodesia between white settlers and local population

- 1975–2002 – Angolan civil war leads to mass displacement and forced migration

- 1977–1992 – Mozambique’s civil war displaces thousands; many flee to South Africa

- 1980 – Southern Africa Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), forerunner to SADC, is formed in order to present economic and political counterpoint to apartheid South Africa

- 1980–1990 – Rhodesian Bush Wars (Zimbabwe’s war of independence) – many migrants flee the country

1990 - 2015: Post-apartheid era

This recent era was characterized by major shifts in the political landscape, and by instability in the region. Ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo sustained high levels of protracted displacement, with children being the largest impacted group (ACERWC, 2019). Migrants fleeing political instability and economic crisis, particularly from Zimbabwe began to flow into South Africa, escalating post-2000 (IOM, 2018, 2010). The migration of female low-skilled workers to South Africa increased in the 2000s and in 2006, female migrants accounted for 30 per cent of all Basotho migrant workers in South Africa (IOM, 2017). Tropical Cyclone Eline and Tropical Storm Hudah heavily affected Mozambique, South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe, including the destruction of agricultural lands which displaced more than a million people (FAO, n.d.).

- 1992 – The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is established with the SADC Treaty

- 2009 - African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) is ratified by only 6 states in Southern Africa (AU, n.d.)

2015 – Present: Era of climate adaptation

In recent years, free movement and labour migration protocols within SADC have seen some progress, albeit no free movement of persons being yet in force. Current projections suggest that Southern Africa will be acutely impacted by climate change (IPCC, 2018). The north east part of the region will likely experience a strong wetting trend while the south west is already increasingly drying and warming, at a rate twice the global average (IPCC, 2018). Water stress has been identified as a major migration driver (Ionesco et al., 2016). Large portions of Namibia, Botswana and South Africa will likely no longer be suitable for cereal crop production in the next sixty years, all things being equal (DEA, 2016: 42). These climatic shifts will produce dramatic effects in terms of livelihoods and food scarcity, which can in turn become major push factors in migration across the region. Fully 80% of Mozambique and Madagascar’s, population as well as 60% of Zimbabwean and Zambian populations depend on agriculture (USAID, 2019; IPR, 2018; Ionesco et al., 2016). Moreover, the small islands of Seychelles, Comoros, and Mauritius face risks related to loss of shoreline and fishing livelihoods, which would create stress to the local populations and could, moreover, function as another factor pushing people to seek employment and land elsewhere.

Southern Africa’s temperature is rising at twice the global rate (IPCC, 2018) with increased frequency and intensity of drought predicted for Namibia, Botswana, northern Zimbabwe and southern Zambia. The displacement impacts of drought in the region are still rarely reported (IDMC, 2019). However, 41.2 million people in 13 countries in the region representing an increase of 28% over the previous year faced food insecurity in 2019, (SADC, 2019). Botswana, Lesotho and Namibia declared a State of Drought Disaster – with Botswana recently facing its most severe drought in 30 years (MPI, 2015). Zambia, Zimbabwe, Eswatini, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are highly vulnerable to food insecurity. Related chronic malnutrition among children is now prevalent in ten countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Angola, and Madagascar (SADC, 2019).

Migration, land tenure security, gender dynamics and water scarcity are interconnected (Curran and Meijer-Irons, 2014). In the face of changing environmental conditions, residents with weak tenure rights are less likely to make long term investments in their land, including climate change adaptation. When arable land depletes, migration then becomes the only risk diversifying strategy. This also has significant impact on women: due to insecure, informal or undocumented land rights, they are often less able to recover land and livelihoods post-disaster.

Food and water scarcity, droughts, floods and cyclones have already displaced thousands in the region. These challenges may become the impetus for enhanced integration, but they could also motivate protectionist behaviours among member states.

Data sources

Appropriate and prompt responses to migratory challenges, as well as the capacity of stakeholders to capitalize upon the opportunities offered by migration, are greatly limited by the fact that timely, accurate information on migratory phenomena is scarce. In this review of publicly available sources, only two main sources with a regional scope for migration data were identified: the SADC Statistical Yearbooks and FinMark Trusts’ remittance data. However, even these sources are highly limited in scope.

Regional aggregations of national data:

- SADC Statistical Yearbook (SYB) - the only official regional aggregation of national data in Southern Africa. Statistics are compiled annually from national statistical offices (NSOs) of SADC member states, as well as the World Bank and other international sources where NSO data are incomplete. The statistics are specific to Southern Africa, and indicators include all relevant countries. Absolute numbers are presented only to a limited extent.

For statistics on migrant remittances, the Yearbook relied on the World Bank’s Migration and Remittances dataset for 7 of the 16 countries (Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia). World Bank figures cannot fully take into account informal remittances and do not always capture funds transmitted through money transfer operators such as Western Union. According to the International Monetary Fund: "where data is available, remittances are measured as the sum of two items in the International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments Statistics Year Book: i) personal transfers, ii) compensation of employees, and iii) migrants’ transfers (i.e., capital transfers between resident and non-resident households). For some countries, data is obtained from the respective country’s Central Bank and other relevant official sources" (KNOMAD, n.d.).2In general, there is little conformity amongst Member States on indicators, collection and analysis of data, limiting comparability.

- FinMark Trust, SADC Payments & Remittances - FinMark Trust and its affiliate, Insight2Impact data portal, offer nationally representative primary survey data for the composite SADC region and all member states. One research programme is dedicated to SADC Remittances and Payments. There are no direct migration indicators, but the site offers a number of finance-related indicators such as sources of income (including remittances), as well as others such as age, education, gender, urban/rural and formal employment. Many indicators have GIS (geospatial) location information tied to them. A 2012 report on remittances in SADC centres on total estimated migration populations (by country of origin) and total estimated remittance flows from South Africa to the other SADC member states through formal and informal channels.

National and multi-country research reports by FinMark Trust also often provide tables compiling their national survey data and other available resources related to remittance flows, such as a recent report on remittance flows between Botswana and Zimbabwe, which also estimates the number of Zimbabwean migrants living in Botswana.

Regional research institutes:

There are several other regional research institutes which publish migration-relevant research. Unfortunately, none of them host comprehensive, regional databases related to migration. Data sets that are available are generally relevant to narrow studies with some of them being qualitative in nature. The most relevant institutions are listed here.

- Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP)

- Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) - also now houses the Africa Institute of South Africa (AISA)

- Southern Africa Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a Migration-themed section of research

- Institute for Security Studies (ISS)

- The African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS)

International Data Resources:

The following databases, created by a wide variety of international organizations, offer regional-level migration data (or country-level with most relevant countries available):

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) provides country profiles and international migrant stock estimates.

- United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), International Migration Statistics

- UNHCR Statistical Yearbooks and Operations Portal

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) disaster and conflict displacement data

- International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Regional office in Pretoria

- International Labour Organization (ILO)

- The Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD)’s bilateral migration matrix

- The EU’s Knowledge Centre on Migration and Demography (KCMD) hosts the EU Dynamic Data Hub which includes a diverse array of migration-relevant data sets, including data on Southern African states

- World Bank Migration and Remittances Data and Global Bilateral Migration Database (GBMD)

Data clearinghouses:

Given the need to rely on country-level data for much of the SADC region and relevant migration indicators, data and survey clearinghouses are an essential resource to efficiently identify relevant surveys. A few of the most useful are listed below:

- Open Data for Africa (data portal)

- International Household Survey Network (IHSN)

- Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) search terms: “International Migration” and “domestic migration”

- Demographic and Health Surveys

- UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS)

Strengths and weaknesses of the data sources

Regional data on migration in Southern Africa are very limited, and existing data are largely on migrant remittances and tourism. Border data, which is a key source for migration flow data, are not publicly available, with several challenges existing regarding the collection and analysis of such data, not least that it is generally obtained for law enforcement purposes. SADC’s Statistical Yearbook remains one of the few sources, with only some relevant indicators included. The most recent yearbook was published in 2015, representing a four-year gap in available data. Where NSO data are limited, the World Bank uses a degree of estimation which limits accuracy. None of these statistics include informal remittances. There are no regional statistics on labour migration – a key migration factor in the region – and its contributions to economic development. A 2018 "Selected indicators" report offers a table on the size of the labour force, but not statistics on migrant labour contributions. The Yearbook also includes a table on "Status on Protocols and Declarations in SADC" by country.

FinMark Trust is the only other regionally-produced source identified. There are clear weaknesses with this source, given that there are no recent, directly relevant indicators available. In FinMark Trust’s research programme, SADC Payments & Remittances, remittances are included as a weighted component of sources of income, by percentage and figures are not presented in estimated volume or real terms. More recent estimates are based on the Trust’s own national surveys presented in the Insight2Impact data portal, together with data drawn from other sources, such as the World Development Indicators. However, the Trust’s 2012 flagship report, which estimated the volume of remittances from South Africa to SADC countries, did not utilize primary data. This research was based on a few key assumptions – in particular, that the stock of migrants is a primary determinant in the volume of remittances. These migrant stock estimates were then combined with assumptions on remittance patterns to derive region-wide estimates. Accordingly, they are only representative and are not comprehensive.3

Among the national statistical offices (NSOs) of SADC’s 16 member states, availability of migration-relevant indicators and data varies widely. Botswana, Mauritius and South Africa are some of the few countries in the region that compile migration statistics from exit/entry immigration cards and work permits (only Botswana) and make this data available on their websites. Botswana also compiles labour statistics from establishment registers and other sources, as well as offers a recent demographic survey which includes a chapter on migration. Other NSO sources include the census and survey data made available by Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, the United Republic of Tanzania (with an exceptional range of migration-relevant indicators on many surveys and censuses) and Zambia. In addition, in countries where pertinent data is generally limited, a few specifically useful sources include a 1993 Census report from Madagascar, Malawi's 2018 census, and the internal migration tables from Mozambique's 2017 census. Availability and comparability of migration data in the SADC region remains a key challenge. Data on slow-onset, irregular migrants and drought-induced displacement also remains a gap.

Additionally, there is no data capturing of non-monetary remittances – a topic that has gained increasing popularity in the transnational migration literature, as well as on the role played by diaspora members in developmental projects within their home countries. Due to data challenges, skills transfer dynamics are mostly omitted. Internal migration remains significant in the region and individuals at times undertake “gradual” movement such as moving to cities to work and save money before moving onwards outside their countries to another SADC Member State or beyond. In effect, internal remittance flows are common, however, reporting on that is hindered by existing data gaps.

Regional stakeholders and processes

In the Southern African region, the complexity of migration dynamics, together with legacies of the colonial migrant labour systems, have hampered on initiatives of regional integration and free movement. No free movement of persons within SADC is yet in force, although discussions to this end formally began in the early 1990s. South Africa has negotiated preferential bilateral agreements on migrant labour and trade with five states in the region (Changwe Nshimbi and Fioramonti, 2013). The complexities in the integration processes among SADC migrants has led to reforms such as the Special Dispensation Permit (SDP) issued among South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique migrants to be able to secure jobs in any of these countries. It would be beneficial to assess through data the progress of this initiative, including the share of migrants issued this permit to the total number of migrants, how this approach influence the likelihood of job security among immigrants from these three countries within SADC, and to measure differences vis-a-vis other countries within the region who do not sign up to this framework. Moreover, economic and political instability in some parts of the region have made many member states reticent to opening its borders freely to all neighbouring states. A brief overview of the historical elements leading up to the present day regional ad hoc systems is presented below.

In 1995, SADC drafted a Protocol on Free Movement of Persons. This protocol laid out a 10-year plan for incremental steps towards regional integration and fully free movement of persons within SADC. However, this was redrafted to accommodate the concerns expressed by South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. The 2005 version was approved by all governments but has only been ratified by six of the 16 SADC members (Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, South Africa, Eswatini and Zambia) to-date. In effect, there is still no regional migration protocol, and labour movements continue to be dictated ad hoc amnesties, bilateral agreements and national labour laws (Changwe Nshimbi and Fioramonti, 2014).

In 2000, SADC and IOM established the Migration Dialogue Process for Southern Africa (MIDSA), a non-binding regional consultative process on migration which allows member states to establish a regular critical dialogue to enhance inter-state cooperation in an effort to improve migration governance (MIDSA, n.d.). Concurrently, South Africa – concerned about the influx of refugees and irregular migrants fleeing countries affected by economic crises and political instability – has proceeded to establish preferential bilateral trade and labour migrant agreements with Angola, Botswana, Lesotho and Eswatini (all fellow members of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU)). In contrast, in its Cooperation Agreements with Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Namibia, South Africa specifies no migration-related arrangements or objectives.

In the past decade, SADC has gained some traction developing a Facilitated Movement of Persons Protocol, which has yet to come into force. The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) has a Visa Protocol in place, but a Free Movement of Persons Protocol has also not yet come into force. In 2009, a Policy Framework for Population Mobility and Communicable Diseases in the region was drafted. The policy framework is, as of April 2020, in revision and awaiting the findings of a regional needs’ assessment. In 2012, Member States established a tripartite agreement between the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC) and the SADC, to fast-track the facilitation of free movement of goods and persons between the three regional economic commissions (RECs), which together cover almost the entirety of the eastern half and southern sphere of the continent (SADC, 2011; Changwe Nshimbi and Fioramonti, 2014). In 2013, SADC agreed its first Labour Migration Action Plan (2013-2015). In 2014, SADC laid out a Labour Migration Policy Framework, and in 2016, outlined a second Labour Migration Action Plan (2016-2019). Moreover, five4 member states have ratified the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) - Eswatini, Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe. It remains to be seen whether a regional migration protocol will be ratified in the coming years.

Attacks on migrants in 2008, 2015 and 2019 induced displacement among the migrant populations in South Africa (Burke, 2019). In response to this trend, the Republic of South Africa approved the South Africa National Action Plan (NAP) to Combat Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance in March 2019.

The ministerial recommendations of MIDSA dialogues in 2017 and 2019 speak directly to the mandate for migration data. The 2017 recommendations encourages Member States “to build capacities to collect, analyze migration-related data to develop policies based on evidence and data to improve migration governance at the national and regional level” (MIDSA, n.d.). The 2019 recommendations include three key mandates: 1) The establishment of national coordination mechanisms on migration to engage national data suppliers, producers, users as well as national research institutions to ensure the effective collection, analysis and use of migration data at the national level. 2) Strengthen regional cooperation on migration data to ensure standardized and comparable migration surveys in all Southern African countries. Migration data collection methodologies and national surveillance mechanisms, inclusive of censuses, should be capitalised on, ensuring that a maximum number of migration-related indicators are included; and 3) IOM is to work closely with governments in the Southern Africa Region to support the development or updating of country-specific migration profiles that are comparable across the region and can be used to inform evidence-based migration policies (Regional Office Pretoria, 2019). As part of IOM’s response to requests by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Member States to enhance governments’ capacities to generate accurate and reliable data to better inform policy development, the Regional Migration Data Hub for Southern Africa (RMDHub) was launched by IOM. The RMDHub is to serve as a central repository of migration data and information gathered through studies, research and operational activities in the SADC Region.

Further reading

International Organization for Migration

2020 World Migration Report 2020. 61-63.

Changwe Nshimbi, C. and Fioramonti, L.

2014 The Will to Integrate: South Africa’s Responses to Regional Migration from the SADC Region. African Development Review, 26(S1): 52–63.

Frouws, B. and Horwood, C.

2017 Smuggled South: An updated overview of mixed migration from the Horn of Africa to southern Africa with specific focus on protections risks, human smuggling and trafficking. Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS) with Danish Refugee Council (DRC). March.

Williams, V. and Tsang, T.

2007 Migration Dialogue for Southern Africa (MIDSA) Report No. 2: The Prospects for Migration Data Harmonization in the SADC. Southern Africa Migration Programme (SAMP), MIDSA Series.

Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), Republic of South Africa

2016 Climate Change Adaption Perspectives for the South African Development Community (SADC), LTAS Phase II, Technical Report (no. 1 of 7). Longer-Term Adaptation Scenarios (LTAS) Flagship Research Programme. Pretoria.

The Nansen Initiative

2015 Disasters, Climate Change and Human Mobility in Southern Africa: Consultation on the Draft Protection Agenda, Report of the Nansen Initiative Southern Africa Consultation, South Africa. Stellenbosch University. June.

International Organization for Migration (IOM)

2017 Study on Unaccompanied Migrant Children in Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Harley, L.

2019 African Countries Relax Short-Term Visa Policies for Chinese in Sign of Increased Openness to China. Migration Policy Institute. August.

Finmark Trust.

2018 Understanding Global Remittances Corridors in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). May.

Heimann, L.

2015 Climate Change and Natural Disasters Displace Millions, Affect Migration Flows. December. Migration Policy Institute.

Wood, T.

2019 The Role of Free Movement of Persons: Agreements in Addressing Disaster Displacement - A Study of Africa. Disaster Displacement.org

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

2019 Democratic Republic of the Congo: Figure Analysis – Displacement Related to Conflict and Violence. May.

African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC).

2019 Mapping Children on the Move within Africa. March.

Crush, J., Peberdy, S. and V. Williams, V.

2006 International Migration and Good Governance in the Southern African Region. Southern African Migration Project (SAMP), Migration Policy Brief No. 17.

Postel, H.

2015 Following the Money: Chinese Labor Migration to Zambia. February. Migration Policy Institute.

Editor's Note: The first infographic was edited on 29 May 2020 to correct the emigration figures.

1 Southern Africa hereby refers to Member States of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), i.e. Angola, Botswana, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, the United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Within the International Organization for Migration (IOM), all these Member States are covered by the Regional Office for Southern Africa, except for the United Republic of Tanzania, which falls under the Regional Office for East and Horn of Africa. This region is not to be confused with the UN Statistical Division’s classification of Southern Africa with the following five countries: Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa.

2 It is unclear if country-reported statistics are based on the same calculation as the World Bank data (the Yearbook’s Technical Notes and Sources manual does not appear to be available online).

3 At the time of research (November 2019), the national survey data link itself was not provided with download instructions.

4 Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa, Eswatini, Zimbabwe

Back to top