Smuggling of migrants

Migrant smuggling refers to the movement of persons across international borders for financial benefit (IOM, 2019, derived from the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime). Data on migrant smuggling allow policymakers to better understand the phenomena as well as to develop policies that promote safe and orderly migration.

Data on smuggling are scarce, and there is no annual global report on migrant smuggling trends. Official statistics on migrant smuggling are limited as many countries do not collect or publish such data. The little data that do exist on smuggling are retrieved from arrivals numbers, such as those across the Mediterranean, or are based on the number of migrants apprehended at a border (Laczko and McAuliffe, 2016). A useful indicator on migrant smuggling and the concern States have over the practice is the number of countries that have ratified the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its supplementary protocol, the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air. However, the extent to which these countries have implemented their obligations remains difficult to determine.

A migrant from the Horn of Africa sits under a tree for shade in Obock, Djibouti. He is waiting for smugglers to organize his group's travel to Yemen. He said he was hoping to make it to Saudi Arabia, as he had known people to go there before and send a lot of money home to help their families. Photo: © IOM 2018 / Olivia Headon

Definitions

According to the UN Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, migrant smuggling is defined as “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or permanent resident” (UNODC, 2000).

Although the terms are often confused, the smuggling of migrants is not the same as human trafficking. An element of exploitation is required in trafficking but not in smuggling. Smuggling must be consensual and it must be transnational, as human trafficking may also occur within a country’s territory. In practice, it may be hard to establish the boundary between smuggling and trafficking, as elements of exploitation and abuse may emerge during transit or at destination, even in the presence of initial consensus on the part of the migrant. Smuggling and trafficking may occur on the same routes and smuggling can lead to trafficking, making it difficult to discern one from the other. It is also important to note that human trafficking is a crime against an individual, whereas smuggling is a crime against the state (ICAT, 2016; UNODC, 2018).

Recent trends

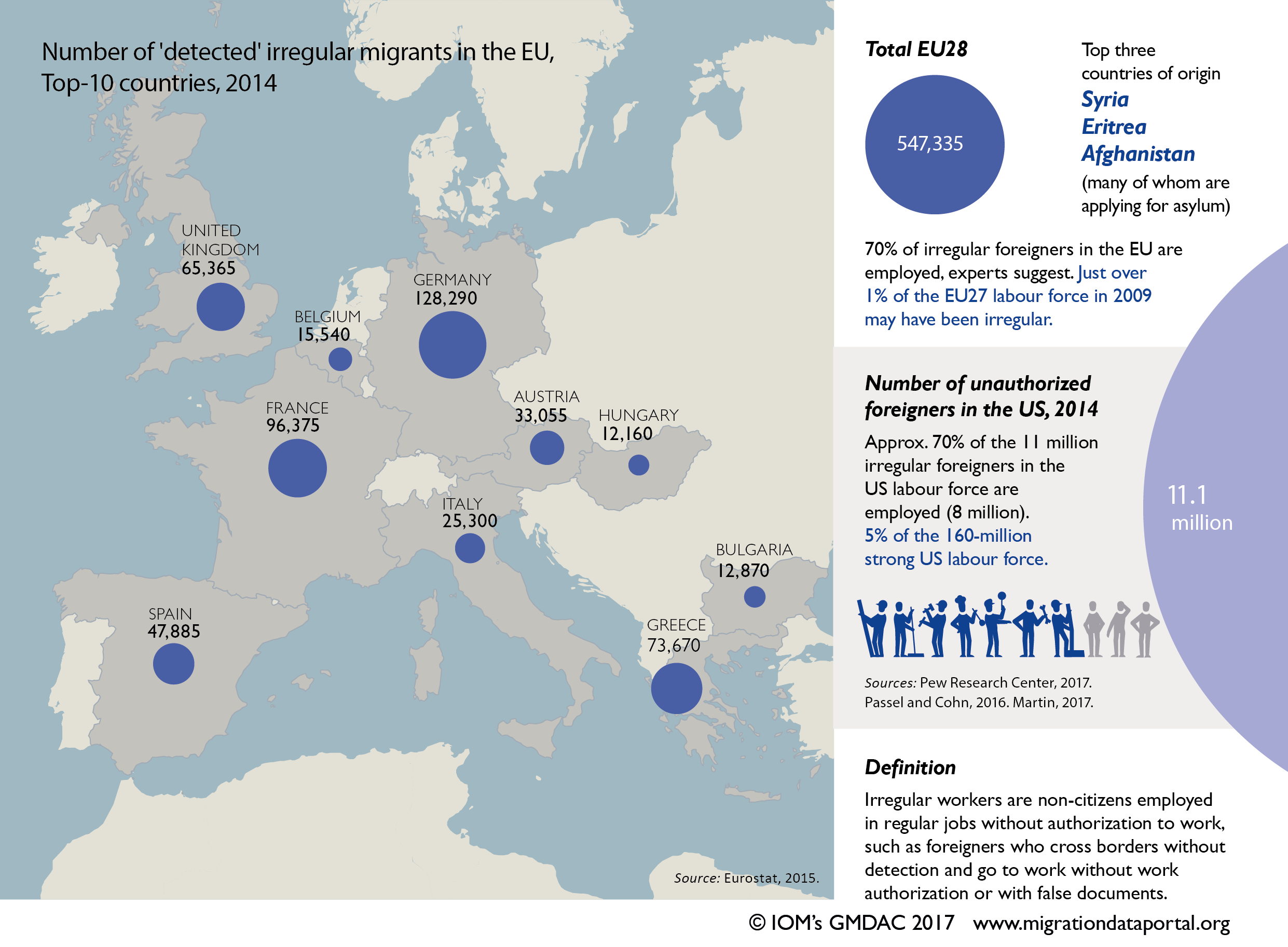

Due to its hidden nature, there is no reliable global statistic on the number of migrants who are smuggled each year. According to UNODC estimates, at a minimum 2.5 million migrants were smuggled in 2016 in exchange for an estimated USD 5-5.7 billion (UNODC, 2018).

Data for specific migration corridors provides an indication of the scale of migrant smuggling. In terms of regional trends, there are an estimated 3 million irregular entries into the United States each year, most of which involve smuggling (UNODC, 2016). As for mixed migration movements to Europe, 292,985 migrants arrived to Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain via the Mediterranean routes and the Western African Atlantic routes in 2023 (IOM 2024), the majority of whom are believed to have used smuggling services. The UNODC reports that annually tens of thousands of people from areas of Southeast Asia and from Myanmar are smuggled to, through and from Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia (UNODC, 2024).

Migrant smuggling is a business that could be worth as much as USD 10 billion or more per year, given that routes from West, East and North Africa to Europe, and South America to North America generate approximately USD 6.75 billion a year (Laczko, F. in Ferrier and Kaminsky, 2017). However, estimating the global revenue generated from smuggling is itself problematic, as for many routes it is difficult to estimate the number of smuggled migrants or the profit gained by smugglers(UNODC, 2011; UNODC, 2018). Measurements of the profit margin of migrant smuggling must be assessed carefully, as there are many factors that contribute to such a number, such as the distance and complexity of the route, the degree of institutional control of the route and the reception of migrants in transit and destination countries (ibid.; see also Global Spotlight: Migrant Smuggling Project).

UNODC (2018) estimated the revenues for smugglers along specific routes per year, for 2016 or earlier as follows: Smuggling into the European Union total for the three Mediterranean routes, USD 320 – 550 million, land routes from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa USD 1-1.5 billion, different routes to South Africa 45.5 million; sea routes from the Horn of Africa to the Arabian Peninsula USD 9-22 million; land route to North America USD 3.7-4.2 billion, from neighbouring countries to Thailand USD 192 million (in 2010), land route from South-West Asia to Türkiye approx. USD 300 million.

A UNODC report discovered that in Nigeria, 28 per cent of smuggling recruitment is done through modern information and communication technologies. 48 per cent of migrants met a smuggler through family and friends, while using phones, socials or in person 38 per cent of migrants approached the smuggler themselves and 14 per cent were approached by the smuggler (UNODC, 2023). However in Southeast Asia, only 13 per cent of those seeking smuggling services used social media, while the remaining 87 per cent used phones or contacted smugglers in person (UNODC, 2024).

Data sources

The UN Office for Drugs and Crime (UNOCD)’s Sharing Electronic Resources and Laws on Crime (SHERLOC) portal aims to disseminate information related to the implementation of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. The Portal provides five databases on Migrant Smuggling: a case law database, a database of legislation, a treaties database, and a bibliographic database. These can be searched using criteria such as crime type and/or country/region, providing user-friendly access to sources on migrant smuggling.

The UNOCD’s Observatory on Smuggling of Migrants provides key findings and StoryMaps on global smuggling routes from Nigeria, Northwest African (Atlantic) route; West Africa, Morocco and Western Mediterranean; and West and North Africa and Central Mediterranean. Each StoryMap contains route-specific explanations and data on elements such as the context, routes, smuggling demand, smuggler characteristics, fees, risks, responses, methodology and maps.

IOM’s Global Data Institute (GDI) brings together two key areas of IOM’s data work —the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) and the Global Migration Data Analysis Center (GMDAC)— which both are engaged with migration data with an extensive global footprint, a deep understanding of the movement of people globally, and an unparalleled global primary data collection system. More specifically, two are the main data collection tools which provide primary data linked to migrant smuggling:

Missing Migrants Project (MMP) collects data on migrant deaths and disappearances worldwide, many of which are linked to smuggling.

Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is a system to gather and analyse data on the mobility, vulnerabilities, and needs of displaced and mobile populations. Including four standard components – mobility tracking, flow monitoring, registration and surveys – DTM collects data at different stages of the migration and displacement journey. DTM’s flow monitoring activities are able to capture migration movements across the main land and sea routes used by migrants globally, involving individuals who may have used smuggling services to cross international borders. Information travel arrangements, costs and facilitations used during irregular migration journeys are also compiled through survey data.

The Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) provides monthly narrative summaries as well as quarterly and annual reports of the mixed migration movements and data in six regions (West Africa, North Africa, East Africa and Yemen, Middle East, Asia and Europe). Both the narrative summaries as well as quarterly and annual reports provide information regarding the number of migrants smuggled, the cost of smuggling and other related information, if available.

Lastly, the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) produces the Annual Yearbook on Illegal Migration, Human Smuggling and Trafficking in Central and Eastern Europe, which includes a survey and analysis of border management and border apprehension data from 22 countries.

Back to topData strengths & limitations

Data on migrant smuggling are very limited due to the hidden nature of smuggling. As smuggling occurs under the radar, it is often not identified or misidentified and consequently not recorded by official sources. Assessing the scale of the problem is therefore a major challenge. While there are measurements of irregular migration around the world, no data exist to determine the extent of migrant smuggling globally (IOM, 2016b).

As irregular migration flows are also generally difficult to measure, due to the lack of knowledge about the dynamics of irregular migration in certain regions, it becomes more difficult to pinpoint the number of migrants smuggled.

While clear quantitative data regarding smuggling may not exist, a number of qualitative data does. Such data provide insights into case studies and migrant profiles, which can inform policy even though quantification may be difficult. An example of such a repertoire of studies can be found in UNODC’s publication on Migrant Smuggling in Asia: Current Trends and Related Challenges, which provides a number of small-scale qualitative studies on smuggling. Such examples of qualitative data reveal the economic and social processes involved in smuggling. However, due to the sensitivity and maintaining the confidentiality of informants, such data are produced in the form of published work rather than raw data (McAuliffe and Laczko, 2016).

More could be learned about migrant smuggling if countries were encouraged to collect and share data on migrant smuggling in a standardized way (ibid.). In addition, new partnerships across research disciplines as well as between policy makers and researchers can be created in order to improve understanding of the various effects smuggling policy may have on smuggling practice. McAuliffe and Laczko (2016) also recommend increasing research in and by countries of origin and transit as well as to expand research on emerging topics.

Further reading

Back to top