For Pacific Islanders, the ocean is a vital economic, social, and cultural lifeline. The region’s twenty one island countries and territories have an ocean-based economy focused on maritime transportation and shipping, fisheries, extractive industries and prospecting for oil and gas as well as tourism. Fishing licensing and revenue fees alone were estimated at USD 474 million in 2016 and are projected to increase. Tourism, a key source of income and employment in the Pacific, contributes in some cases up to 70% of a country’s GDP. While estimating the monetary net worth of the ocean remains a challenge, the value of ocean resources is deeply acknowledged by the Pacific peoples. Rural communities focus on fishing and aquaculture for their livelihoods and there is a high dietary reliance on fish. Shells, marine mammal ivory and pearls are central to Pacific jewellery and other decorative products.

Climate change represents the most important existential threat to the Pacific way of life, and it will exacerbate other challenges already affecting the region. While there is consensus among researchers about the detrimental impact of climate change on the ocean, what is less studied is what impact the changes in the environment will have on Pacific Islanders’ livelihoods, security, culture and well-being. Having more evidence on this is crucial for Pacific Islanders’ to better prepare and adapt for an uncertain future, and for decision makers to understand what the responses imply for demographic and migration trends.

Who are the Pacific Islands?

Source: Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, 2005 report, available from http://projects.inweh.unu.edu/inweh/display.php?ID=773

The climate change-ocean-migration nexus: What we know

The Paris Agreement, whose long-term goal is to enhance climate action to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees, only made a single reference to oceans. Since then, Pacific countries and territories have advocated strongly for acknowledgement of the “climate change-ocean nexus”, resulting in the upcoming twenty-fifth Conference of Parties under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to assess progress in climate action to be dubbed the blue COP.

The idea of the nexus is rooted in data and evidence. Scientists agree that climate change is contributing to an increase in sea temperature, as a large share of excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions is absorbed by the ocean. At the same time, studies show that the ocean is becoming increasingly acidic and is losing oxygen. This combines with the adverse consequences of sea level rise and extreme events, although with varied extents across the Pacific region. Climate change acts as a threat multiplier especially in areas already affected by pollution, overfishing, overpopulation and degradation of biodiversity. Cascade impacts may denote a potential decline in number and health of fish stocks due to warmer water; migration and dispersion of fish species; inland shifting of mangroves; changes to seagrasses; salinity intrusion in farmlands; coral bleaching and subsequent degradation of its ecosystem.

These changes in the ocean increasingly affect the physical, economic, political and social drivers of human migration through direct and indirect impacts on the human security of populations dependent on natural and ocean-based resources or living in areas exposed to hazards.

The climate change-ocean-migration nexus: What we don't know

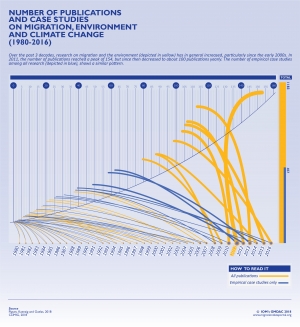

There are a large number of scientific studies exploring ocean changes related to climate change, but fewer on how this affects food, water, health and livelihood security. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s fifth assessment report mentions that though there is high confidence on the degradation of coral reefs, there is poor understanding of the implications for those communities dependent on these.

Indeed, while there is a consensus that coral reef or atoll nations like Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Republic of the Marshall Islands will be most affected, not enough is documented or examined on how coastal communities experience these changes, their adaptation responses and limits. In cases where this information exists, dissemination continues to be a challenge.

In the context of climate migration, significant focus of the global discourse has been on complete inundation of islands and potential relocation. Discussion and data on current human migration trends, both internal and cross-border, how climate change drives these, the process and outcomes especially for rural ocean-dependent communities remains lacking.

Research conducted under the Pacific Climate Change and Migration project from 2013-2016 noted that over 60 per cent of respondents in Tuvalu and Kiribati would migrate if sea level rise, salt water intrusion and floods continue and are aggravated and if there are fewer fish in the sea. However, further research needs to understand how many people are highly dependent on marine resources, current coping strategies for these populations, expected adaptation strategies and migration trends- where would they go and what would they do? Based on such case studies, models should be scaled up to understand potential macro-level impacts and implications for national policy.

At the same time, migration continues to be perceived as a negative demographic trend. Research is required to demonstrate if and whether migration either to the main islands or overseas, contributes to climate change adaptation and sustainable development. This entails understanding how migration serves as a means for rural households, especially fishing communities, to diversify their income sources, enhance their knowledge and skills and support long-term household planning.

How do we move forward?

When it comes to climate migration, “we don’t have enough evidence” is a common rhetoric amongst governments and non-government organizations alike. This can be simplified to two sets of key ingredients: firstly, the scientific evidence that lays out future climatic projections and secondly, the social science that provides an insight into future demographic trends influenced by climate change. Together this information supports long-term planning beyond current planning cycles, allocation of resources, identification of required capacity both at the national level, but also amongst communities to enable them to be prepared and develop context-specific solutions. Some of the national level responses may be strengthened or complemented with actions at the regional level, which calls for greater regional consultation.

A group of researchers from academic institutions across Australia (The University of Queensland, The University of Melbourne, University of Canberra and CSIRO), funded by the Australian Research Council, are investigating Transformative Human Mobilities in a Changing Climate in partnership with IOM, UNESCAP and the Pacific Conference of Churches. The project intends to provide clear case studies and evidence that identifies pathways to which vulnerable populations, including fishing communities, can use migration towards a sustainable future.

This will feed into the Pacific Climate Change Migration and Human Security joint-programme, led by IOM and will contribute to national and regional discussions on how to ensure that communities, especially those reliant on marine and other natural resources, can stay where they are or benefit from moving.